When the weather in Germany is overcast and calm, the windmills and solar plants don’t send any power to the grid. Instead, they send shockwaves through the markets. One such “Dunkelflaute” day in mid-December saw spot power prices climb to more than €900 ($939) per megawatt-hour – nine times above average. That’s even higher than the increases in 2022, when the nation lost access to Russian pipeline gas after the invasion of Ukraine.

Article content

(Bloomberg) — When the weather in Germany is overcast and calm, the windmills and solar plants don’t send any power to the grid. Instead, they send shockwaves through the markets. One such “Dunkelflaute” day in mid-December saw spot power prices climb to more than €900 ($939) per megawatt-hour – nine times above average. That’s even higher than the increases in 2022, when the nation lost access to Russian pipeline gas after the invasion of Ukraine.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Article content

Article content

With price spikes happening more frequently as the use of renewables becomes increasingly common – wind and solar currently supply over half of Germany’s electricity – the country’s energy regulator is proposing a bold experiment to keep the grid stable.

In order to continue receiving generous subsidies, about 400 manufacturers will have to adjust their operations to match real-time wind and solar supply. That means ramping down production during periods without wind or sunshine, and running at full throttle on breezy, bright days when spot prices can turn negative.

This should help keep a lid on prices, encourage renewable uptake in Europe’sF biggest economy and insulate the country’s energy flows from black swan events. Germany’s energy regulator, the Federal Network Agency, has until the end of March to present the plan, agency head Klaus Müller told Bloomberg, and a final decision is expected later this year.

The change will force some companies to completely rethink how they operate. “How will I shift my production?” asked Heinrich Eufinger, the managing director of cement producer HEUS Betonwerke GmbH, a family business in the municipality of Elz near Frankfurt. “It doesn’t make sense to have workers arrive in the morning and then send them on a three-hour break because there is no wind or sunshine.”

Article content

Advertisement 3

Article content

While Germany’s renewables buildup has been the fastest in Europe, the nation lacks reliable back-up power. It pulled the plug on nuclear energy two years ago, and a plan to build new gas-fired plants was scrapped by the government last year. If adopted, the experiment would be the biggest to address this problem, although similar efforts to make industrial production more flexible are being tested in smaller countries such as Denmark.

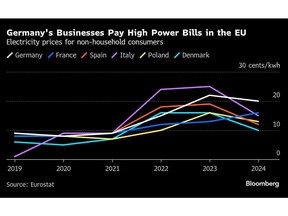

It’s a high-stakes moment to force through an industrial transformation at this scale. Rising energy prices have already trammeled growth in Germany and forced some manufacturers to move production abroad. A trade war is looming between the United States and China, and Donald Trump is also threatening the EU with tariffs.

With less than two weeks to go before Germany’s next election, both main parties have said they oppose penalizing companies that cannot adjust to so-called “flexible demand.” Yet neither have final say in the matter. The Federal Network Agency is independent, meaning its decisions can’t be overturned by political decree, though they can be challenged in court.

Advertisement 4

Article content

This debate is also playing out as part of a bigger conversation about what should happen when Germany’s current grid fee reduction expires in 2028. For the past two decades, industrial manufacturers have been able to recoup up to 90% of their grid fees — around €1 billion in total — in exchange for consuming huge volumes of steady, uninterrupted power. Those costs, which are covered by businesses and households, pay for the construction and maintenance of power lines. Keeping this model in place past 2028 isn’t an option – the subsidy is out of alignment with EU climate targets, and it can’t be renewed without a significant overhaul.

In other words: manufacturers get subsidies for constantly using power, and while they can’t exist without those subsidies, many have designed their operations around constant energy consumption. That means that even if flexible demand becomes policy and companies adopt it in order to keep getting grid fee reductions, they’ll still have to make major — and potentially costly — changes.

Part of the problem is that the subsidies were designed before renewables made the grid more dynamic, explained Jochen Bammert, a physicist and team leader at Stuttgart-based energy company TransnetBW GmbH. Unlike in the days of nuclear, coal and gas, when grid management was mostly uneventful, “my colleagues have to constantly intervene in the grid, stave off bottlenecks, switch off wind or solar plants or order gas plants to be ramped up,” he said.

Advertisement 5

Article content

Individual energy consumers can help operators balance the grid by reducing use at high-demand moments. But for now, most manufacturers aren’t as flexible – and they worry the proposed reform could inflate their energy costs.

That could prove fatal, warned Maximilian Strötzel, who heads industrial policy for the board of trade union IG Metall. With electricity prices soaring and subsidies incentivizing high use, he said, “the situation of some industrial companies is already existential.”

Aurubis AG in Hamburg, one of the world’s largest copper recyclers, receives around €15 million a year in grid fee reductions. It cannot simply switch on or off its smelting furnace, said Ulf Gehrckens, who heads the company’s Energy and Climate department. A spokesperson for Infineon Technologies AG, Germany’s largest semiconductor manufacturer, said that chip production “depends on extremely constant operating conditions, around the clock.”

The Economic Council, a conservative-aligned business association that represents more than 12,000 firms, echoed this concern in a letter to economy minister Robert Habeck last year. Although flexible demand could benefit some firms, it conceded, for a large number of companies with “continuous production processes,” it is “out of the question.”

Advertisement 6

Article content

Helen Rolfing, a project manager at climate thinktank Agora Industry, has also proposed a gradual reform that would build in transition periods to give companies time to invest in new processes without increasing the overall cost for consumers. Rolfing recently co-authored a study on flexible demand which found that some companies benefiting from the current subsidy could increase their savings.

Among them is a paper mill in Bavaria run by the Finnish group UPM Communication Papers. While the Augsburg-based factory cannot easily turn its paper machines on and off, it has spent decades optimizing its wood pulping processes. Now, when cheap excess power is available, UPM shreds wood chips into fibers and puts them in storage. When there’s a grid bottleneck, workers simply stop that machine.

One option being considered to encourage uptake is expanding the subsidy to many more companies. Injecting around €2 billion from the nation’s budget — a controversial proposal — would effectively triple the funding available for grid fee reductions, according to people familiar.

Advertisement 7

Article content

In principle, adopting flexible demand would make sense for ZINQ, a family business in Germany’s industrial rust belt that produces stainless steel surfaces, that doesn’t currently recieve the grid fee reductions. Chief executive officer Lars Baumgürtel said that during peak load times the company’s smeltering ovens can be powered by either gas or electricity. But as the current infrastructure can’t provide as much electricity as is needed, “that would take strong new power lines.”

When the Gelsenkirchen-based business asked its local grid operator to estimate how much it would cost to connect just one of their roughly 50 factories, the estimate came back at €2 million.

“That makes power way too expensive for us,” Baumgürtel said. “We’ll stick with gas for the time being.”

—With assistance from Eva Brendel.

Article content