MBW’s World’s Greatest Producers series sees us interview – and celebrate – some of the outstanding talents working in studios across the decades. Here we talk to Hoskins, a US-based UK producer who has worked with artists including Post Malone, Morgan Wallen, Beyoncé and many more. World’s Greatest Producers is supported by Kollective Neighbouring Rights, the neighbouring rights agent that empowers and equips clients with knowledge to fully maximise their earnings.

Jonathan Hoskins knew his destiny. Having studied Music Technology at the University of Hertfordshire in the UK, he told all his friends and family that he would have a No.1 record within two years of his 2011 graduation.

“After two years, I didn’t have a No.1,” he chuckles. “In fact, I didn’t even know anyone in the music industry! If someone had told me at that point it was going to take this long to get to the point of extreme success, I would maybe have stopped earlier!”

But he didn’t, and a mere 12 years behind schedule, the producer’s wildest predictions are now coming true, as he’s on a streak even hotter than the Los Angeles’ sunshine he’s currently basking in, having decamped to California 18 months ago.

He worked on I Had Some Help, the smash hit by Post Malone featuring Morgan Wallen, that topped the US Hot 100 last year and is still rattling around streaming charts 10 months later. As well as two other tracks on Posty’s F-1 Trillion album plus Wallen’s Whiskey Friends, he’s also featured on Teddy Swims’ blockbuster I’ve Tried Everything But Therapy (Part 2) album and Beyoncé’s groundbreaking Cowboy Carter.

But if it is, as he himself points out, somewhat surreal for a grime-loving kid from Southend to end up the toast of Hollywood and Nashville, Hoskins – as he’s known professionally – has certainly earned the right to be there.

Having discovered grime via pirate radio, he spent his teens running home from school to make beats on FruityLoops software and sending them out to rappers on MSN Messenger or releasing them on SoundCloud. He joined a grime collective before deciding to branch out musically after realising he “didn’t know any grime producers than owned a house”.

He went to music college in East London and then the University of Hertfordshire, which opened his eyes to “what it would be like to be a professional musician”. Eventually realising he’d have to make things happen himself, he headed for London, where, in meeting after meeting with publishing A&Rs, he was told his sound was “very American”.

So he asked everyone in his network to introduce him to “someone cool” in LA and got involved in a K-pop camp in Seoul, meeting key collaborators such as Charlie Handsome (“Our 10,000 hours of work on different areas within music just sync up really well”) and Digi along the way.

From there, he enjoyed breakthrough tracks with Khalid’s Alive (“He was the biggest artist in America, Spotify stats-wise – being part of something given the stamp of success in America really gave me a kick on”) and PartyNextDoor’s The News (“People were doing reaction videos – I used to look at those things and they’d be about big, notable songs, but now it was about one I made: that put me on the other side of the glass”) before moving Stateside full-time.

He doesn’t rule out a return to the UK at some point but, for now, he’s embracing the California kale’n’yoga lifestyle (“At first I thought it was stupid, but then I realised that, if you don’t do that in America, you’re eating weird chemicals that are banned in Europe – you either go full weirdo health guy or die at 40!”) while maintaining the very English self-deprecation.

Despite the hits, he has kept a low profile so far (Google ‘Hoskins’ and you’ll wade through pages of The Long Good Friday tributes before you find him), although, with a load more potentially huge projects in the pipeline (“I’m trying to make stuff for all of the biggest artists in the world”), that might not be the case for long.

But for now, the producer/writer – managed by Milk & Honey and published by Sony Music Publishing – settles down with MBW for a rare interview to talk country music, TikTok and why AI is welcome to his old sound…

Are you pleased you took the slowburn route to success?

Yeah. If I didn’t do it day-by-day, step-by-step, I probably wouldn’t have got there. But, in turn, that means you don’t really take it in.

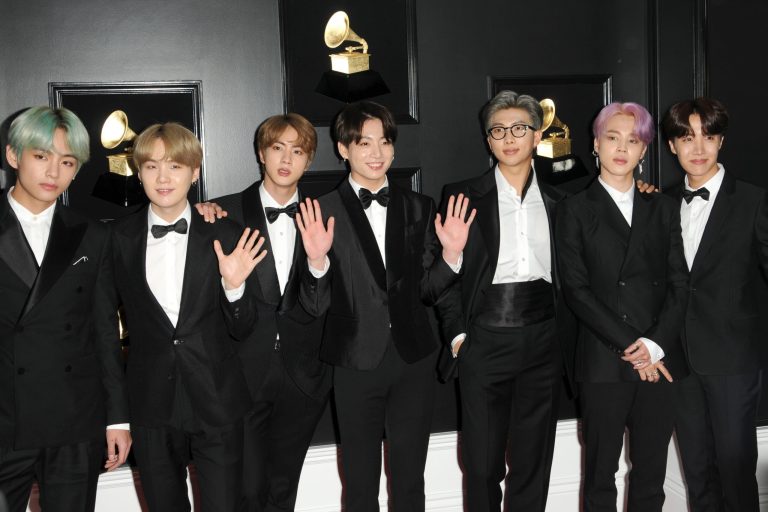

When I went to the Grammys I was like, ‘Wait a sec, this is actually pretty cool’. I was on the red carpet and people were asking me questions. I really took that in – otherwise, I’m just making music as I have been doing every day for 15 years.

What does a hot streak like this do for your career? Is your phone ringing off the hook?

Yeah, but it’s more nuanced than that. There are some good talkers in the music industry – I’m getting invited to a few more lunches now, and there are a few more, ‘Dude, you should come to this show and come backstage’. Then, at the show, they’ll be like, ‘So, I’ve got this new artist – I need some songs’.

One thing that’s great is, people listen to my songs with a different ear now. There are a lot of great ears in the music industry, but a lot of the time they’re hearing so much stuff it is very useful to have the public’s co-sign on some of your music.

Now, when your song comes across their desk, they’re like, ‘OK, let’s actually listen to this one twice’ or, ‘Let me wait for it to get to the chorus, because this guy’s got a track record’.

“For the first six months of being in LA, I was just in grind mode and I didn’t have much out that was particularly hot.”

Plus, everybody I wanted to work with in terms of songwriters and producers, as soon as this stuff started coming together in a row, pretty much all of them were down to work, which was great.

For the first six months of being in LA, I was just in grind mode and I didn’t have much out that was particularly hot. I was just getting my head down and trying to get my word of mouth up. That combined with having songs actually out, so suddenly it was, ‘OK, I’ve heard this guy’s name, this song’s doing well and he’s on these albums, maybe he’s actually good!’

Did you expect to make so many country records?

It wasn’t part of the plan, but I rolled with the opportunities as they came.

It stemmed from my close collaborator Charlie Handsome – he moved to Nashville and was hitting me up like, ‘Dude, I’m in Nashville, send me some stuff, I’m working with these big country artists’.

I’d listened to some country in passing – when you’re from England, you’ve heard of Dolly Parton and Johnny Cash and that’s about it!

I took the parts I felt connected to and repurposed them into country, but my country. I wasn’t trying to do Waylon Jennings super-legit traditional country, I’m not going to do that better than them. What I can do is, take the essence of country and the parts I connect to and frame it in a way that sounds good and see if they like it.

And it turned out that was an asset to the process of making country albums. There are so many amazing musicians, writers and producers in Nashville, but they’re all in the Nashville bubble and a lot of them are making similar stuff. By the time I started making country, it was aligning with them being open to more experimental music.

I initially didn’t even think I was making country, I thought I was making guitar pop and I put some sounds in there that probably wouldn’t feature in a country song.

My first one with Morgan Wallen, Whiskey Friends, had some strange sound design going on, I did a weird vocal thing that they ended up leaving off the final record, but I guess it inspired something in the room that wasn’t there. And then people started being like, ‘This guy’s got some cool stuff’.

Is it very different making records in Nashville compared to London or LA?

It’s a cool place to go and change perspective. It has a very different approach; in Nashville, the song comes first. In LA, sometimes people will be jamming out on instruments for two hours and then be like, ‘Shall we do some melodies?’ and then, by the time there’s a whole vocal melody and a whole track made, people will start being like, ‘So, what’s the concept?’

Whereas in Nashville, before a string is played or a key is pressed, they’re talking about the concept.

When I first went there, I was astonished that people would talk about the title, figure out all the lyrics and then they’d be like, ‘Can we record this?’ I was thinking, ‘Did anyone talk about a melody?’ But then they’d sing it and it was like ‘Oh, there was a melody, but I didn’t even hear you guys discuss it because that comes secondary’.

I like to take that, sprinkle it in with the LA melody-based approach and then I’m aiming for the ultimate song, where it’s a great lyric, great concept, great melodies and some cool production!

Do you mind how many producers are credited on a track?

I don’t mind if everyone’s contributing something.

The music industry has changed – back in the day if someone wrote a guitar riff on a song, they’d be credited as a guitarist and it was ‘produced by Quincy Jones’.

Whereas now, if you write a guitar riff on a song, you’re probably going to be a producer. If something started as a jam with five people, they’re all probably going to be credited as producers now, whereas before they were just a band.

So, it looks like way more people are working on songs but it’s probably not actually that different to how many people were working on it before, it’s just people treat the musicians differently, which I’m not mad at. If someone contributes a key part, then go ahead.

But I don’t really love it when stuff gets super-passed around – I always like to have the chance to do it myself. I play instruments, programme drums and finish songs, so I’d always like the shot. And if I need a specialist to come in and help, I know people who will deliver for me on that.

I’d love to be in control of who’s on the song, but I’m not one of those people who’s really mad at having six people on there. Maybe people are just getting the credit they deserved – if you write an iconic riff and you’re just in the liner notes, that’s tough.

If you could change one thing about the music industry, right here and now, what would it be?

I wish labels would allocate points to songwriters that are not producers. A songwriter that’s on a song and isn’t performing or producing is going to be the only person getting no master royalties and that should change.

Especially with the way streaming is now, you make so much more for the master points than the publishing points if it’s a streaming hit. It would be a lot fairer if they just gave a couple of per cent to the songwriters.

I see myself as a producer who helps write. I’ve got huge respect for the songwriters out there who are listening to random interview clips with a philosopher from 1920 and writing down concepts like, ‘Maybe I can make that into something palatable for 15-year-olds today’. A great lyricist is invaluable to a room, especially someone like me, who spent their formative years learning the technical side of stuff.

Do British writers and producers have to go to LA to make it now?

The main hub in the world is LA. You can have a great career in London, Miami, Nashville but, if you want to have the most reach, LA is definitely the place to be.

My career completely changed as soon as I moved here – and I knew that it would. If you’re in London and you’re working with Ed Sheeran or Dua Lipa, great, stay in London. But if you’re wanting to work across a lot of different stuff, then it’s all happening here.

Why do you think British music is struggling internationally?

I wish there was more patience with developing artists. The stuff that isn’t working on TikTok gets passed over pretty quickly, in favour of stuff that is working on TikTok, but maybe has no substance.

They’ll say, ‘This has got this many plays’, but it might just be a funny video with that song in the background. It’s taking the emphasis away from who the artist is.

“it has turned into stat-based A&R, in the UK especially, where people are a little less willing to take a big risk.”

A lot of it has turned into stat-based A&R, in the UK especially, where people are a little less willing to take a big risk. When I was in the UK, I found it really difficult to get in with artists that I knew I would work well with. I knew, if I could just get one session in with them, I could help make some great music.

But, because I didn’t have songs in that specific genre or wasn’t co-signed by the right person in the UK, they’d go with the safe bet and have this person work with them instead. People in America take more risks in terms of signing and in terms of trying stuff with other creatives.

Do you ever think about TikTok when you’re producing a track?

No. It’s not the best approach. I guess sometimes in the back of my mind I might think, ‘I’ve heard this type of chord progression work on TikTok before’, but that’s not the ultimate goal for me, to have a song go viral on TikTok. I’d rather make music that’s impactful.

All respect to people that are going up on TikTok right now – some people know how to make that work, but transitioning those songs off TikTok into the charts and onto the radio is a whole other challenge. So, I’d rather just aim for the latter and then, if it goes up on TikTok too, great.

Will AI have an impact on production?

I didn’t think it would particularly until recently, when I had a look at one of the music generation things and came across some stuff where I was like, this is a better sample than I would find in a record shop.

So, if I was a sample-based producer, I’d be on the AI websites all day just generating stuff. It’s effectively like digital crate-digging and that will have a huge impact, especially in hip-hop. But, currently, I’ve mainly used it to write songs about my girlfriend’s dog in the style of the Beach Boys!

I would love there to be some sort of legality and recompense for the artists that are getting referenced. It’s a grey area, but I’d like there to be a precedent set where the actual creatives are getting paid, because it’s a bit dicey at the moment.

Aren’t you worried someone will be able to press a button and make a song sound like it was produced by you?

I’ve never been someone that will hide my process. I find it useful as a motivation to keep my sound evolving. If you could make a programme that makes something that sounds like my production, then I haven’t moved along quick enough – that should be my old sound and I should be on my new sound by now. The AI can have my old sound!

Kollective Neighbouring Rights is one of the largest and most efficient neighbouring rights agents in the world. KNR navigates a complex and detailed income stream whilst providing clients with unmatched transparency, monthly accounting and flexible statement solutions.Music Business Worldwide