Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the UK inflation myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

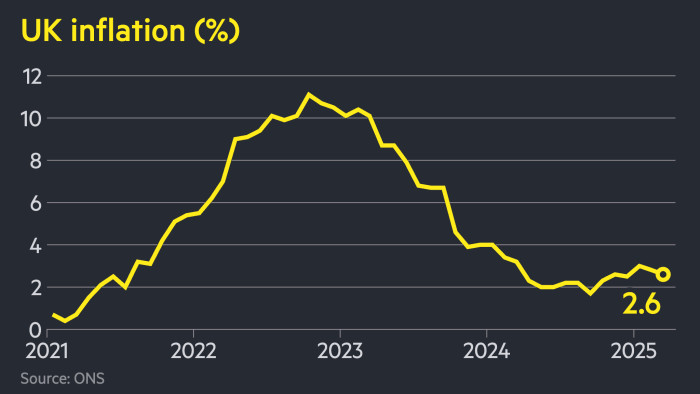

UK inflation fell more than expected to 2.6 per cent in March, bolstering the case for the Bank of England to cut interest rates next month as it braces for the economic impact of US President Donald Trump’s tariffs.

The annual increase in consumer prices, reported by the Office for National Statistics on Wednesday, was below the 2.7 per cent forecast by economists in a Reuters poll and down from 2.8 per cent in February.

The figures showed the biggest factors in the drop were lower prices for petrol and for games, toys and hobbies — in particular computer games.

But services inflation, a key measure of underlying price pressures for rate-setters, slowed more than expected to 4.7 per cent in March from 5 per cent in February. Food inflation also eased, from 3.3 per cent to 3 per cent.

“For once, UK inflation fell for the right reasons,” said Tomasz Wieladek, chief European economist at T Rowe Price, who said softer services inflation would give the BoE confidence “that the disinflation process in the UK is on track” and allow the central bank to cut rates in May.

Following the release of the data, traders cemented their bets on at least three quarter-point cuts from the BoE by the end of the year, according to levels implied by swaps markets, with the chance of the first coming at May’s meeting put at 85 per cent.

The yield on two-year gilts, which move with interest rate expectations, fell 0.06 percentage points to 3.91 per cent.

The pound initially edged lower against the dollar after the data before regaining ground, up 0.3 per cent at $1.328 on the day.

Wieladek added that the softer inflation data and the fears over trade had opened the door to “at least four” rate cuts this year.

Rachel Reeves, chancellor, said two months of falling inflation, combined with growth in GDP and real wages, were “encouraging signs” — rebutting claims by shadow chancellor Mel Stride that the government’s policies were “keeping inflation higher for longer”.

But economists said the dip would not prevent inflation rebounding in April, reflecting sharp increases in regulated household bills, and that the longer-term outlook would depend on how global trade policy evolved.

“The truth is that the outlook for UK inflation hinges on President Trump’s tariff policies,” said James Smith, research director at the Resolution Foundation think-tank.

The BoE has been balancing the risks of a weakening jobs market against the ongoing pressures of strong wage growth and higher household bills.

The central bank’s Monetary Policy Committee said last month it would stick with a “careful and gradual” approach to cutting borrowing costs after holding interest rates at 4.5 per cent.

But the impact of a global trade war will now dominate the BoE’s thinking.

The UK has been hit by Trump’s across-the-board 10 per cent tariff and by the 25 per cent levy the White House has imposed on imported cars and steel. But economists say slower global growth, and the unpredictable effects of trade diversion, will have a bigger impact on the UK economy.

Clare Lombardelli, a deputy governor at the BoE, said last week that tariffs were likely to depress economic activity but that their effect on inflation would be harder to forecast.

“Global trade uncertainty could drive down our prices, with oil already down more than 10 per cent since the start of April — but a global trade war would create renewed inflation,” said Smith.

Ruth Gregory, deputy chief UK economist at the consultancy Capital Economics, said the tariff shock “has tilted the balance of risks towards lower inflation and faster falls in interest rates”.