Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

You have to go back to 2015 for the last time the British electorate rewarded the status quo. Since then they have voted for Brexit and Boris Johnson, and come close to backing Jeremy Corbyn in 2017. At the last election it was enough for Sir Keir Starmer simply to put the word “change” on the front of his manifesto and leave the details to voters’ imagination. For a decade, the country has been consistent that things cannot go on as they are.

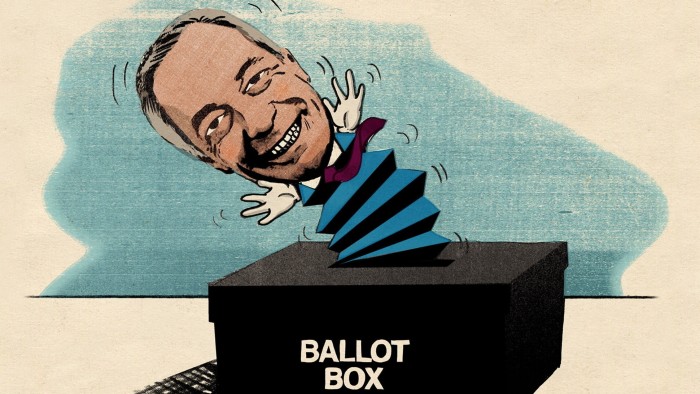

This week’s local elections in England will follow that trend. Even if Nigel Farage’s Reform UK party underperforms its headiest predictions, it looks set to cement its status as a major party, capable of superseding the Tories as the main opposition to Labour.

But though allies and rivals will focus on the potency of its populist nationalism, there is a danger of over-interpreting its success. One cannot dismiss the power of the immigration issue or the Tory implosion that Reform is exploiting, but there is a broader and simpler explanation for its rise. Britain is going to keep voting for change until it feels it has come and Farage is the latest beneficiary of that thirst. Reform’s momentum is less about its programme than its claim to the change mantle. That is why Farage, whose personal ratings remain highly negative, is now working to broaden his platform.

For proof, one can look at where else the votes are going. If polls are correct, the combined Greens and Liberal Democrat vote will be as large as Farage’s. The combined share for Labour and the Tories is likely to be dismally low. The vote is fraying in every direction but theirs. It is possible to become a major player with a far lower share of the vote.

MPs on doorsteps report that, just months after backing Labour’s nebulous pledge of change, voters now see Starmer’s defining act as the cutting of pensioner winter fuel payments. To them, this was a betrayal. Not change, but Labour austerity.

The main causes of disaffection have not changed since the 2008 financial crisis: the cost of living, high immigration and public services — the NHS especially. And beneath this is a simpler sense that Britain has stopped functioning as it should, that the state has become unresponsive, that the country is getting poorer.

The UK is following the European pattern of citizens deserting the main parties for alternatives offering a more radical breach with the past. It is no accident that one of Farage’s favourite lines is that Labour and the Conservatives are an indistinguishable “uniparty”. Such is the frustration that it matters ever less whether parties offer realistic programmes. Then again, was Brexit ever a serious solution?

So how can Starmer respond to the disillusion? A growing caucus will urge him to veer left. It argues that Labour should worry more about the voters it is losing to the Lib Dems and Greens because of excessive fiscal discipline and pandering to social conservatism. Others advocate the so-called “Blue Labour” agenda of chasing Reform in pursuit of a traditionalist white working-class vote.

But salvation does not lie in higher welfare spending, a harder line on Israel or a softer one on trans rights. Nor, as the Tory leader Kemi Badenoch is discovering, in trying to out-Farage Farage. If the Reform leader is what people want there is already a working model. At best, Blue Labour offers a defensive measure against populist nationalism that ignores the party’s newer reliance on liberal graduate voters.

The only answer is to satisfy voters that the transformation they demand, from prosperity to health to balanced immigration, is actually at hand. Yet Labour does not display the dynamism that conveys this. Even where its goals are transformational, it appears too slow and timid, its ambitions checked by economic malaise.

Some of this comes down to Starmer’s manner, much to the economic inheritance and some to the financial and political constraints Labour placed on itself in opposition. It failed to prepare voters for hard choices which is why its support has proved shallow. But there have also been too many half-steps because of conflicting priorities. It is in danger of satisfying no one by trying to placate everyone. If securing growth was truly the primary mission, the key that unlocked other priorities, was it wise to rush through large tax rises and other measures that undermine business confidence and investment?

Those around the prime minister say there will be no change of course, no loosening of fiscal rules or feint to appease the party left. But the next three months will see a burst of activity including the long-promised 10-year plan for health, though Downing Street’s view of the early draft is that more work is needed. The new industrial strategy and an immigration plan are imminent. British disdain for Donald Trump is emboldening Starmer to edge closer to the EU as he negotiates a reset of relations. Allies accept there needs to be more pace and visible conviction that reflects the impatience of voters, not least because it will take time for them to feel any effects.

There are years until the next election and, as Canada’s election showed, the landscape can change in weeks. But Reform’s progress and the broader flight from the two main parties is a sharp warning to Starmer that he is a long way from convincing voters they can finally call off their search for that elusive party of change.