June 7 marked the 50th anniversary of the opening match of the first men’s Cricket World Cup. And now is an ideal opportunity to revisit the tournament, with a World Test Championship final just around the corner.

The one-day limited-overs format had begun in England in 1962, as a means of reviving a struggling county competition. Australia followed suit in 1969/70, with the New Zealand national side defeating Victoria in the final.

The first One-Day International took place at the MCG on 5 January 1971. It was unscheduled, and played only to bolster the Australian Cricket Board’s coffers following the abandonment of an Ashes Test without a single ball bowled. The following four years would duly feature 84 Tests, but just 18 ODIs.

The ODI and its flagship event have come a long way since then. While the format’s future might be uncertain, its contribution to the game’s culture and prosperity should not be understated.

The format

England had already hosted and won a football World Cup in 1966, and the inaugural women’s Cricket World Cup in 1973. It was the obvious location for a first men’s cricket equivalent. England’s cancellation of a scheduled tour by South Africa created a window for both the tournament, and a four-match Ashes series.

The only six Test sides at the time were Australia, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan and the West Indies. To create an eight-team competition, invitations were also extended to Sri Lanka, and to a combined East Africa side representing Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia.

The tournament comprised 15 matches, and was completed within 15 days. And each round’s four games took place on the very same day, with broadcasters not demanding a one-match-a-day schedule. By comparison the 2023 version was triple the size, with 45 matches over the course of 46 days.

Each side’s innings comprised 60 overs, with each bowler restricted to 12. Balls were red, clothing white, and no day-night matches were played. There was no restriction on bouncers, or strict interpretation of wides. And there were no fielding circles either, let alone Power-Plays and Super Overs.

Total prizemoney was £9,000, including £4,000 for the winning side, £2,000 for the runner-up, and £1,000 for each losing semi-finalist. Each pool game’s Player of the Match was awarded £50.

By comparison the 2023 tournament’s prize pool was 500 times larger, at $US10 million. It included $US4 million for the winner, $US2 million for the runner-up, $US800,000 for each losing semi-finalist, $US100,000 for each non-qualifier, and $US40,000 for each pool match won.

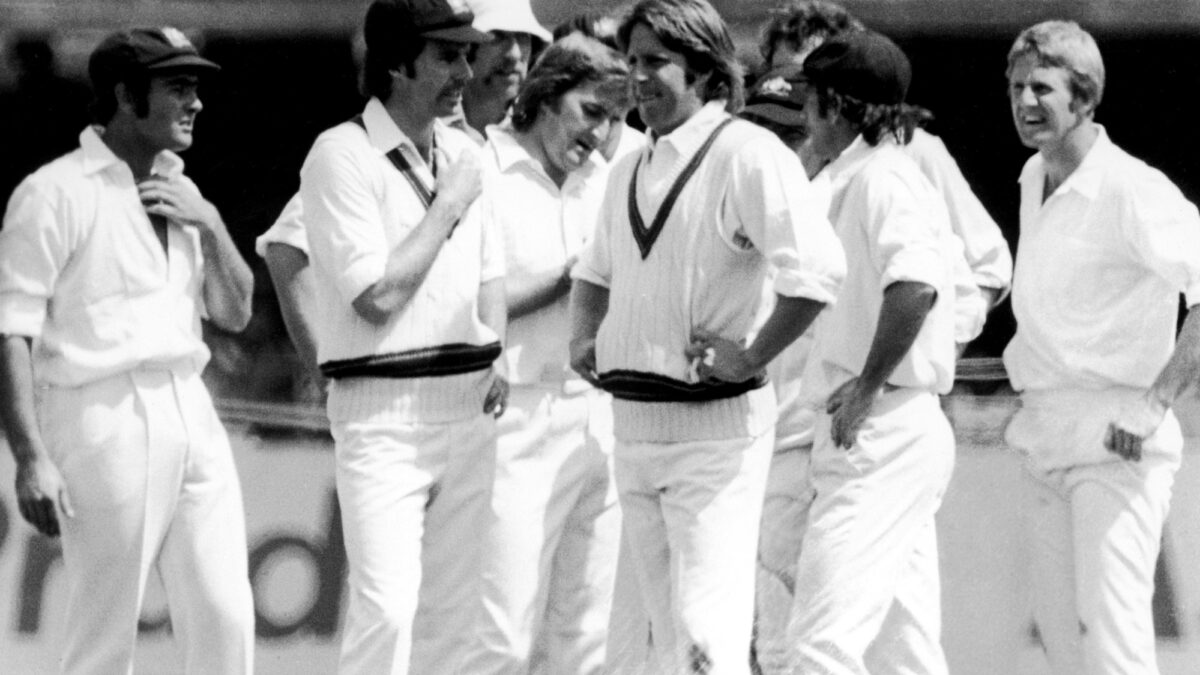

Jeff Thomson after taking a wicket at the 1975 World Cup. (Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

The sides

England’s side boasted immense limited-over experience while other teams also boasted county professionals such as Keith Boyce, Rohan Kanhai, Majid Khan, Clive Lloyd, Glenn Turner and Zaheer Abbas. Bookmakers duly installed the West Indies as 9/4 tournament favourites, followed by England (11/4), Pakistan and Australia. East Africa was a rank outsider at 1500/1.

Australia picked effectively their Test side, and after the World Cup was over the entire squad remained in England to defend the Ashes. Its tour party was Ian Chappell (c), Greg Chappell, Ross Edwards, Gary Gilmour, Alan Hurst, Bruce Laird, Dennis Lillee, Rick McCosker, Ashley Mallett, Rod Marsh, Jeff Thomson, Alan Turner, Max Walker and Doug Walters.

Of those 14 players, Hurst and Laird ultimately did not play a single match, while Gilmour did not make an appearance until the finals series.

The pool games

If the opening match at Lord’s was intended to give a wonderful first impression of the World Cup concept, it failed. The home side did amass 4/334, with Dennis Amiss (137 from 147 deliveries) exorcising his Ashes demons. However in reply, India limped to a dismal total of 3/132 from its 60 overs.

The chief contributor to the go-slow was Sunil Gavaskar (36 from 174 deliveries, including just one boundary) who used the occasion for centre-wicket practice. After the match his team manager GS Ramchand stated: “It was the most disgraceful and selfish performance I have ever seen… his excuse was, the wicket was too slow to play shots but that was a stupid thing to say after England had scored 334.”

Australia comfortably disposed of Pakistan and Sri Lanka, with Greg Chappell (45 and 50), Edwards (80no), McCosker (73), Turner (46 and 101), Walters (59) and Lillee (5/34) showing welcome form.

Thomson hospitalised Sri Lanka’s Sunil Wettimuny (with a broken foot from consecutive sandshoe-crushers, as well as a fractured rib) and Duleep Mendis (who he struck in the forehead).

The Aussies then ended their pool matches with a loss to the West Indies, despite the efforts of Edwards (58) and Marsh (52no). Its opponent’s key contributors were Andy Roberts (3/39), Roy Fredericks (58) and Alvin Kallicharran (an exhilarating 78 from 83 deliveries, including 35 from Lillee’s last 10 balls).

The tournament’s closest match took place at Edgbaston. The West Indies defeated Pakistan by just one wicket with only two balls to spare, thanks to a 64-run last-wicket partnership between Deryck Murray and Andy Roberts. The result would prove crucial to the World Cup’s eventual outcome.

The undefeated England and West Indies topped their respective pools. Australia and New Zealand also qualified for the semi-finals, with records of two wins and one defeat apiece. NZ’s team featured dual-centurion Turner, and three Hadlee brothers in Barry, Dayle and Richard.

Sunil Gavaskar. (Photo by Jason McCawley – CA/Cricket Australia via Getty Images)

The semi-finals

Australia’s eventual selection of Gilmour, for its knockout match against England at Headingley, paid dividends. He delivered one of the great all-round World Cup performances, swinging and seaming the new ball prodigiously from the Football Stand end. His unchanged spell of 6/14 from 12 overs reduced the home side to 6/36. Walker (3/22) then removed the tail, and England totalled a mere 93 from 36.2 overs.

The visitors struggled similarly with the bat, and slumped alarmingly to 6/39. Fortunately Walters (20no) and- you guessed it- Gilmour got Australia home with an unbroken 55-run seventh-wicket partnership. Man-of-the-Match Gilmour’s contribution was a run-a-ball 28, with five boundaries.

At The Oval on the very same day, the West Indies secured their place in the decider with a comfortable win over New Zealand. Bernard Julien (4/27) and Vanburn Holder (3/30) restricted the Kiwis to 158, despite the efforts of Geoff Howarth (51) and captain Turner (36).

They were overtaken for the loss of three wickets, with Alvin Kallicharran (72 from 92 deliveries) and Gordon Greenidge (55) sharing a 125-run stand.

The final

The tournament’s eagerly anticipated decider took place at Lord’s on Saturday 21 June, the longest day of the year. It pitted an Australian side that had crushed England only months previously to regain the Ashes, against an exciting West Indian one supported by an excitable- and effectively home- crowd. The weather was perfect, as it had been for the tournament’s entire fortnight.

Ian Chappell won the toss and invited his opponents to bat first, a decision which reaped early rewards when the early loss of Fredericks, Kallicharran and Greenidge reduced it to 3/50. Fredericks was unlucky to tread on his wicket in the act of hooking Lillee for six.

Captain Clive Lloyd (an imperious 102 from 85 balls) and the veteran Rohan Kanhai (55 from 105 deliveries, despite at one stage remaining scoreless for 11 overs) turned the game with a 149-run partnership, and late cameos by all-rounders Boyce (34) and Julien (26no) took their team to a final score of 8/291 from its 60 overs. Gilmour (5/48) continued his semi-final form.

The Times’ John Woodcock wrote of Lloyd that “His innings will always be talked about while those who watched it are still alive. He made the pitch and the stumps and the bowlers and the ground and the trees all seem much smaller than they were.”

When Australia batted, it took the game deep despite losing wickets at regular intervals. Viv Richards announced himself to the world with a brilliant fielding display, highlighted by running out first Turner and Greg Chappell with direct hits, and then brother Ian (62 from 93 deliveries) as well, to reduce their side to 4/162. Lloyd (1/36 from 12 overs), still a useful bowler at that time, then bowled Walters.

After Walker became Australia’s fourth run-out victim, its last pair Thomson and Lillee required 59 runs from eight overs for an unlikely victory. They had whittled their target down to just 24, when a run-out appeal prompted a pitch invasion despite umpire Dickie Bird having ruled Thomson not out.

From the very next delivery, Lillee was caught off a no-ball, and hundreds of spectators again invaded the ground. In the ensuing chaos, he and Thomson kept on running, adding valuable runs to the Australian score. Bird was robbed of his hat and some fielders’ sweaters, and the ball was also lost.

Play eventually resumed, and three balls later a fifth run-out delivered the West Indies victory by 17 runs. The last of the day’s ground invasions would cost Thomson his pads, and Boyce his boots.

Lloyd was presented with the Player-of-the-Match award, for a brilliant all-round performance crowned by the only century of his 87-match ODI career. And a capacity crowd of 26,000 had witnessed the longest day’s play in cricket history, which began at 11.00am and finally ended at 8.43pm.

What happened next

Ian Chappell retained the Ashes in England, before handing the captaincy reins to brother Greg. His side retained the Frank Worrell Trophy by a 5-1 margin, with Lillee and Thomson at their intimidating best. It then drew with Pakistan, defeated New Zealand and won the Centenary Test, before relinquishing the Ashes.

Amazingly in hindsight, the Australian Cricket Board scheduled just one home ODI during the three summers that followed the World Cup. However media mogul Kerry Packer had attended its final, and two years later he would sign up most of that match’s participants, and many of the tournament’s other stars, to participate in a competition he dubbed ‘World Series Cricket.’

A few months after his side had been bullied in Australia, Lloyd’s three-man spin attack could not prevent India from scoring 4-406 to win a Test in Trinidad.

His consequent change to a pace battery comprising Roberts, Michael Holding and Wayne Daniel destroyed England in 1976, and would soon be enhanced by the likes of Colin Croft, Joel Garner and Malcolm Marshall.

The West Indies would go on to successfully defend its World Cup title in 1979, and dominate world cricket for almost two decades. However they failed to qualify for the most recent tournament, after losing a qualifying match to Scotland.

The West Indies during their 1980s glory days. (Photo by PA Images via Getty Images)

Viv Richards quickly developed into one of the finest batters of all time. In the 1976 calendar year he scored a then-record 1,710 runs at 90.00, highlighted by 829 at 118.42 in England including individual innings of 291, 232 and 135.

India unexpectedly won first the World Cup in 1983, and then hosting rights for the 1987 tournament. Those two achievements changed the direction of world cricket. Sunil Gavaskar went on to represent it in four World Cups, was a member of India’s triumphant 1983 side, and scored a century in the 1987 tournament in front of his home crowd.

Sri Lanka gained Test status in 1981, and Kenya participated as a stand-alone team in five World Cups. The overall number of participating sides gradually increased, reaching 14 for the 2011 and 2015 tournaments.

The number of ODIs played annually peaked at 218 in 2023, then more than halved to just 104 matches in 2024. And the International Cricket Council, after introducing an ‘ODI Super League’ for World Cup qualification in 2019, abandoned the concept in 2023.

The format’s future is uncertain, given the competing demands of Twenty20 World Cups, World Test Championships and Champion’s Trophy tournaments, as well as the growing number of domestic Twenty20 leagues.

Its fate may ultimately rest on what the Board of Control for Cricket in India prioritises. I can foresee it surviving for financial reasons, with India hosting every second tournament, and England (and perhaps very occasionally Australia and New Zealand) each intervening one.