Alamy

AlamyBlending the style of The Rolling Stones with African beats and instruments, Zambian group Witch were revolutionary – then disappeared. No one could have predicted their amazing return.

In the early 1970s, Zambia produced a unique music scene of its own creation. Zamrock, as it became known, was the southern African country’s take on western rock music – a take that mixed the sounds of The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix and Black Sabbath with its own fuzz-guitar psychedelia and African instrumentation, beats and rhythms. Forged out of the country’s independence from its British colonisers in 1964, its blossoming came during one of the most significant, fascinating and prosperous periods in Zambian history, and its decline and fall mirrored that of Zambia itself in the late 1970s and early 1980s. A once thriving local music scene became devastated by economic, cultural and health factors that also decimated the wider population, leaving Zamrock as a relic, unknown outside of its own region.

Lizzie Austin

Lizzie AustinYet over 50 years later, Zamrock is enjoying an ongoing revival. While many of the scene’s originators – acts like the influential Rikki Ilonga and his band Musi-O-Tunya, The Ngozi Family, The Peace and Amanaz – have long since either died, stopped performing or are little known, one band has brought Zamrock to a contemporary global audience. Formed in 1971, Witch (an acronym for “We Intend to Cause Havoc”) were the scene’s biggest and most popular band. Fronted by the charismatic Emmanuel Chanda – better known as “Jagari”, a name inspired by Mick Jagger – Witch released five albums between 1972 and 1977 that epitomise the Zamrock sound. “We had the influence of rock and roll, but we were Africans, so we couldn’t play the actual rock and roll,” Jagari tells the BBC. “We had to fuse some things in.”

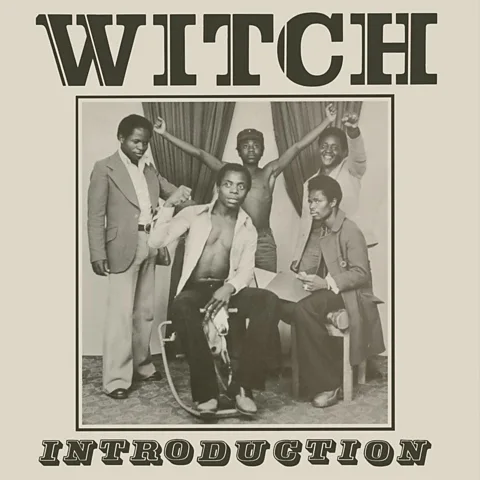

Witch’s unlikely rediscovery started in 2011, when Now-Again Records released a compilation of the band’s music, We Intend to Cause Havoc!, leading to a resurrection that has seen Witch tour the world, release new music and become the subject of Italian film-maker Gio Arlotta’s 2019 documentary, We Intend To Cause Havoc. “It’s hard not to be blown away when you hear Witch,” says Now-Again founder Eothen Alapatt, known as Egon. “The first two Witch records [1972’s Introduction and 1974’s In the Past] have this garage, Rolling Stones type of vibe to them, and those are really great. They’re heavy and just really raw expressions of rock music. But then you get to the third one [1975’s Lazy Bones] and out of nowhere, it becomes like this progressive psychedelic thing. I was like, ‘There has to be a breadth of music here that’s worth exploring.'”

The Witch revival has spread far and wide, leading to renewed interest in Zamrock as a whole. Jack White is a fan, releasing Witch live music on his Third Man Records label; Beastie Boys’ Mike D, Clairo and Madlib are admirers. Moreover, rappers Tyler, The Creator, Travis Scott and Yves Tumour have all recently sampled Zamrock bands, extending the genre’s sphere of influence to the biggest names in cutting-edge hip hop. This week, they release a new album, Sogolo, while later this month they will become the first Zamrock band to perform at Glastonbury Festival. “Zamrock is facing a rebirth, if you like,” Jagari says. “It had died down, it had sunk in oblivion. But the interest is growing.”

How Witch formed

Zamrock originated amid the copper mines of northern Zambia, known then as Northern Rhodesia. Jagari had grown up in one such area, Kitwe, having moved there at the age of eight to be brought up by his older brother. “The colonial masters didn’t completely neglect the black community,” Jagari says, and it was at the weekend social clubs built for the miners that a young Jagari first saw music performed. “In the village, I heard people sing, and I saw them dance. Those little things stuck in my head.”

Jagari would listen to a radio station in Mozambique that played the UK top 40 (often when his brother was working night shifts) as well as jukeboxes in pubs. He was part of a generation hooked on western acts, who wanted to play their music. “Whoever played the guitar during that time was judged by how well he would play [Jimi Hendrix’s] Hey Joe,” Jagari smiles.

Encouraged by his schoolfriends, who saw him dance and mime at local ballrooms, Jagari auditioned for the band that became Witch. He changed his name because he reminded friends of Jagger when performing, although he was initially ambivalent about making the switch. “That bothered me. I don’t want to live in somebody’s shadow. Yeah, he’s a great man. But I’m an African and my nose is flat, and how can I be compared to someone?” But he went to the dictionary and discovered Jagari “meant a brewer of dark brown sugar [in the local language]. Now it made sense to me.”

Partisan Records

Partisan RecordsIt was Zambian Independence in 1964 that laid the cultural foundations for Zamrock. The economic boom that followed, thanks to the rise in demand for copper, had a twofold effect: allowing people more disposable income to spend on going out and on buying instruments, and giving them more exposure to western music on TV and film. But what made a greater difference was President Kenneth Kaunda’s “Zambia first” policy. As a former musician himself, Kaunda wanted to promote local talent and gave bands the platform to succeed, ruling that 95% of radio play should go to Zambian artists. “He declared that we should not always be copycats,” Jagari says. “So it opened Pandora’s box, musically. Now everyone had an opportunity to go and record so they could be heard on the radio.”

For Jagari and Witch, this meant that rehearsals cultivated a merging of western and African sounds. Witch would practice covers in the morning, then “after lunch, we were experimenting with our own ideas. And it worked,” says Jagari. He calls what they came up with as “the Zambian type of rock and roll. That’s the Zamrock interpretation. When we tried them at the gigs, we found the audience were overwhelmed. So then we had an opportunity.” With no real infrastructure – recording studios were rudimentary, even the studio in Zambian capital Lusaka where Witch made 1975’s highpoint Lazy Bones – and no real record industry to speak of, Witch self-released Introduction, the first ever Zamrock record, printing the vinyl in Nairobi, and sold it at their own shows. “I came with 300 copies, because they were all we could carry, and in two shows, they were gone. Because for the people, it was the first time they were going to have a local band, having local material and a local record out, so everyone wanted to have a copy.” Witch self-released their first two albums, but would eventually release music under a subsidiary of Teal Records.

Zamrock was soon thriving. “There was the exotic element of it being the only scene in Africa that played such fuzzed-out guitars and were really into this heavier side of rock music,” says Arlotta. “Whilst in Nigeria it was funky, in Ethiopia it’s more jazz and so on.” While Witch went heavy on the psych-rock, other acts took the same source material and took slightly different approaches. “The Zambian scene has all the subgenres,” Egon says. “It was complete. And that you don’t really find in many scenes.”

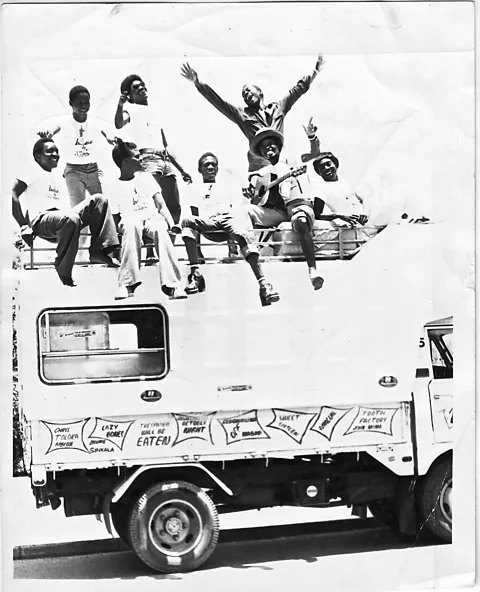

Witch’s gigs are the stuff of legend – they toured in a truck with a canopy emblazoned with the words: “Trespassers will be eaten” – and were must-see events: these marathon shows could last from 7pm to 2am, and were so popular that there crowds outside the venues, locked out but clamouring to come in. The Times of Zambia once wrote: “The hall where the boys played had its roof ripped off as exuberant fans tried to find their way through the windows.” Jagari earned a reputation as a wild and flamboyant frontman. “He just moves around like a madman,” Arlotta says. “He’s a very hard worker, on stage he gives it 110% every single time.” “I don’t know whether we should call it a secret ability,” Jagari says. “I don’t usually plan my moves, I let the music determine what I should do.”

Witch

WitchPerhaps one surprising aspect of Zamrock was its lack of politics. While you might assume a scene spawned from a specific locale known for its historical struggles might carry with it a message, there was – initially at least – little angst or social commentary. That did change towards the end of the scene – Witch’s 1975 track Motherless Child being one such example – but for Zamrock bands, most of whom sang in English, music was a celebration of freedom.

“Initially, when I first heard Zamrock, I thought it was a very rebellious sort of music,” Arlotta says. “When I spoke to the people that lived it, I realised that they had won the battle for their independence 10 years prior to that. So it was more of an aesthetic and a fashion that they followed. There’s many of the lesser known Zamrock songs that praise the President, saying, ‘He’s our leader,’ ‘We love Zambia,’ and stuff like that. You think it’s punk, but it’s really not. Its [sentiment is]: “We were free doing whatever we wanted.'”

A devastating decline

Eventually, though, politics became impossible to ignore. Like most scenes, Zamrock couldn’t last. But its eventual decline was slow, devastating, and attached to much wider existential events across the country. Copper accounted for 95% of Zambia’s exports, so when the price of the metal fell dramatically in the mid-70s, it brought about a sharp economic decline. “If you have to debate between buying [music] or buying a bag of staple food, that impacts negatively,” Jagari says. “And to an extent, musical instruments were regarded as luxury. They attracted high taxes. So we couldn’t afford instruments.”

Furthermore, civil war in the neighbouring countries on the Zambian border was intensifying. Unlike in Zambia, where independence had been achieved by peaceful means, conflicts in Mozambique, Namibia, and South Africa became violent: as one of the so-called Frontline States – a coalition of countries who opposed South Africa’s apartheid rule and supported black liberation – Zambia became a target in the crossfire. “They would bomb some camps in Zambia, where they suspected they had freedom fighters camped,” Jagari says.

President Kaunda’s answer was to declare blackouts and a curfew between 6pm and 6am. It left Zamrock bands with nowhere to play (other than “teen shows” in the afternoon that “nobody wanted to come to”, as Jagari says) and no means of income. “The curfews and blackout impacted us negatively, because we couldn’t play music at night. If you wanted to play music, you had to be in a venue from that time until the following morning, which was not practical, only machines would do that.” In its place, many venues became discotheques, popularising disco and funk music, and moving Zamrock to the margins.

To compound matters, Zambia suffered a catastrophic Aids crisis that killed an estimated 1.4 million people up to 2023. This included many leading figures on the Zamrock scene – among them Jagari’s original Witch bandmates Chris “Kims” Mbewe, “Giddy King” Mulenga, Paul “Jones” Mumba, John “Music” Muma and “Star MacBoyd” Sinkala. “It was not a very nice time,” Jagari says. “And it was not only the musicians that died that during that time, all across the board, soldiers died, teachers died. The economy wasn’t too good, we had curfew and blackouts, and then the Aids came to finish the sad story.”

Now Again Records

Now Again RecordsAfter Jagari left Witch in the late 1970s, they continued without him as a disco-influenced band under the leadership of keyboardist Patrick Mwondela, who changed the line-up until the band ended in 1984. However, Zamrock slid into obscurity, a once vibrant expression of freedom all-but forgotten by anyone who wasn’t there. “A 15-year period where they’re making all these records, and then all of a sudden they’re all gone.” Egon says. “The cassettes have taken over, just like they did in other parts of the world, the turntables get thrown out, and the records become worthless artefacts that no one cared about.”

Jagari left music behind at the start of the 1980s, training as a teacher before becoming a born-again Christian in the 90s and going into gemstone mining. “It wasn’t easy.” Jagari says. “I tried to become a gemstone miner, and the purpose was if I struck big in the gemstone mining, I would buy my own equipment and set up a studio. That was my dream.”

A watershed moment

The course of history changed for Jagari, Witch and Zamrock more widely when Now-Again released We Intend to Cause Havoc! in 2011. Around 20 years ago, Egon, who specialises in unearthing and re-issuing forgotten music, was given unmarked cassettes of Zamrock music via friends of friends through his hip hop label Stones Throw Records. Most of it was Witch; Egon then tracked down Jagari. “He had bought the master tapes, then lost them. But he had the tapes transferred. When I met him, he was selling CDRs of Witch’s music on the streets in Lusaka.”

It led to interest in the band outside of Africa for the first time. In 2012, Arlotta was sent the 1975 song Strange Dream by a friend. “And I was like, what is this? It was something that sounded very familiar, but also completely different, because they had their own twist to it. The recording quality and the way it was recorded was different. The drummer was a lot groovier.” He took a trip to Zambia with some childhood friends in 2014 and decided to track Jagari down to make a documentary. He found Jagari at work in a mine, doing what looked like hard labour. “He’s an intelligent man,” Arlotta says. “I think at first he thought that music was ‘something that I used to do’. And there was this battle between being a rock star and being a born-again Christian. Obviously, in church, if you’re leading a band called Witch, they’re very superstitious about these things down there.”

Both Egon and Arlotta, who managed Witch until January 2025, brought Jagari out of Africa for events and one-off gigs. Arlotta organised Witch’s first tour outside Africa in 2017, with a band including second-era member Patrick Mwondela. Rapturously received shows across the UK, Europe and America led in 2023 to Witch releasing their first album in 39 years, Zango, recorded at Lusaka studio and released on Desert Daze Sound, in partnership with Partisan Records. Witch’s new album, Sogolo, cements their position as pioneers. “It’s pushed a lot of boundaries,” Arlotta says of Sogolo. “It’s got the roots there, but it’s also experimenting a lot with a more modern sound, which is what they were doing back then.”

Now Again Records

Now Again RecordsIn many ways, Jagari is the last man standing: Arlotta calls him “an evangelist” for Zamrock. “There are others just as important,” Arlotta. “But he is certainly the only one touring the world.” He is the artist shaping the legacy of Zamrock. “Legacy is an interesting question,” Egon says. “Because I think the Zamrock legacy is that great creativity can come from anywhere, and it can last. The stuff about Zamrock is that there were artefacts left. And it proves you could be from anywhere. You didn’t have to have a great studio, you didn’t have to have a major distribution deal. You didn’t have to have anything. Your music could literally stay in the confines of one country. And you could create something so good that decades later, people aren’t just going out and looking for it, but people are totally taken by it.”

“I think the success that Witch is having worldwide,” Arlotta says, “and with things that are happening, like Tyler, The Creator, sampling [Ngozi Family] in one of his latest tracks, it’s slowly putting Zamrock on the map.”

As for Witch, they have reached an audience around the world. “With Witch, you can make a case for them alongside any other great band, from anywhere,” Egon says. “Anybody who hears their music doesn’t say, ‘That’s cool for African rock music.’ They’re just like, ‘Wow, that’s great.'”

And now Witch will become the first Zamrock band to play at Glastonbury, a hugely significant moment for a genre that began 55 years ago. “It’s a good feeling,” Jagari says with a smile. “But there’s this tendency at the back of my mind to think how I wish that the [rest of the original] band was still alive, and some of those bands which were prominent that time, if they were alive, then the world would see what Zambia was doing that time. Unfortunately, somebody has to carry the torch on. And that is me. Because it’s ours. The way Rhumba is to Cuba and Congo. The way Amapiano is to South Africa. The way highlife is to Nigeria. Zamrock is our own.”

Witch play the Shangri La stage at Glastonbury on 26 June. The Glastonbury Festival takes place from 25 June to 29 June.