A regular Wednesday afternoon at Roskilde Festival’s central refund station. Dealing with hundreds of items for each person, the wait in line usually lasts several hours.

Intro: Roskilde Festival is more than ‘just a music festival’ – they say

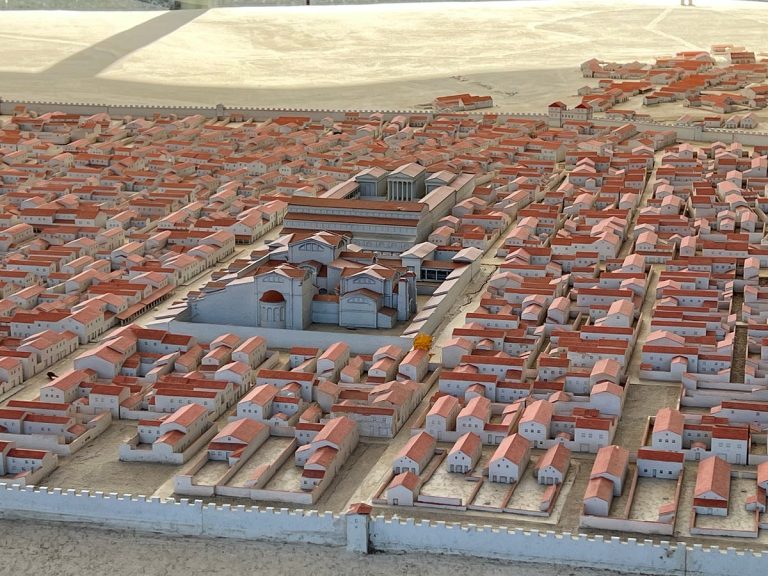

There’s an ongoing joke in Denmark: once a year, ‘Roskilde Festival’ becomes the fourth largest city in the country. What started as a small student gathering in the 1970s, the music celebration—held not far from Denmark’s capital, Copenhagen—has grown into one of the largest temporary cities in the world, with 130,000 tickets sold last year.

The festival is widely regarded as a national cultural staple, a symbol of friendship, liberation, and freedom, part of the coming-of-age of many young Danes. For instance, in the words of Hanna (fictional name), a young university student at Copenhagen Business School, who writes in her exam paper:

“[…] it is so much more than just a music festival. It is a place where you go to bed in a freezing cold tent, only to wake up gasping for air in a sauna […] It is a place where you promised yourself you’d save money and only eat mackerel (ed. Danish herring, a popular canned meal) in tomato sauce but somehow find yourself chasing the food trucks as soon asthe festival site opens. It is a place to return to year after year, and where you can be who you really are or become someone new […] because Roskilde Festival is a free space.”

How could one not feel drawn to such a romantic narrative? Roskilde Festival seems to feel like the place where boundaries dissolve and the potential for self-discovery thrives. Perhaps, for some, the most authentic version of themselves is waiting in a tent at the campsite.

When considering the narrative surrounding the festival, it feels like much more than a party. One example is the festival’s most famous tagline: to be the beholder of the ‘Orange feeling’—a reference to the iconic ‘Orange Stage,’ which has defined the event’s skyline since its beginning decades ago.

And what is Roskilde’s famous ‘Orange feeling’? In a 2016 after-movie, many attendees were asked about it. One girl points out its universality: “[…] everyone has heard of the Orange feeling.” Another guy articulates it as “once you get to this side of the fence, there is no rule, you can do whatever you want.” It seems that Roskilde Festival embodies a mix of love, openness, fun, and carefree energy in the air—a secret recipe that makes it so life-affirming.

Roskilde Festival presents it as a sort of Arcadia version 2.0, shaped by contemporary priorities and progressive ideals. True to the essence of utopian visions, this “new pastoralutopia” offers a space to focus on life’s pleasures: forming human connections, dreaming with music, and experiencing a boundary-free environment. At the same time, the festival integrates easy-access activism, branding itself as “a movement” while operating with the legal status of a non-profit organization.

Various media outlets have described the festival as being at the forefront of the seemingly perfect intersection of art, innovation, and people: “[Roskilde Festival] is an experimental space for art, sustainability, cultural projects, new ways of creating community and addressing societal issues. A free space where young people explore new perspectives basedon art and creativity. And a real-time innovation lab for testing out new products and ideas.” (creativedenmark.com, link)

What many do not realize is that while the locals are partying, hundreds work in the shadows—playing a crucial role in keeping the festival from imploding under the weight of trash. Each year, a growing number of individuals from marginalized communities, primarily from Romania and West Africa, travel north to collect empty beer bottles, cups, and cans discardedby thousands of festival-goers, exchanging them for cash through the Danish refund system. Roskilde Festival acknowledges that more than 300 refund collectors from about 15 countries visit the festival annually.

Refund collectors are queuing and waiting to exchange their bottles for the deposit.

Bottle collectors can be found in most countries that have implemented a deposit system for bottles and aluminum cans. While this practice serves as one of the many “side hustles” for individuals living below the poverty line throughout the year, it is during the “festival season” that the scale blows out of proportion. In the case of Denmark, for instance, entire families travel north specifically to make a living from the empty beer cans thrown around by the Danes.

An ordinary “Pant machine” in the back of a grocery store in Copenhagen. “Pant” is the Danish name for the items eligible for the refund system.

However, this job is far from being “easy money.” It requires a physical and mental strain beyond the individual capabilities: the effort is 24/7, and after being in constant movement for a week straight with little to no sleep, collectors quickly become exhausted and sick. Facing fierce competition among an increasing number of people joining the festival for refund collection purposes every year, the collectors work in harsh conditions without an official acknowledgment by the festival’s management.

Bottle collectors operate in a gray area of regulations. Many festival goers mistakenly believe the refund collectors are employed as cleaners by the festival, but this is not the case. They are all paying for a regular, full festival ticket.

How does this bottle collection process fit into Roskilde Festival’s ‘Orange feeling’? How do the collectors live the festival experience? And how does it relate to what the festival promises and promotes? To find out, I spent the entire week at last summer’s festival. Between concerts and parties, I spent my time volunteering in the “Refund stations”—designated spots where empty containers can be exchanged for money—and learning about the collectors’ daily lives.

First encounters with the ‘Orange Feeling’: the Crowd, the Trash, Lars, Marlene, Joe

The arrival at Roskilde Train Station. Trains run from Copenhagen to Roskilde every 20 minutes; however, every ride is incredibly packed during the first few days.

The festival’s opening day, June 30th, had arrived, and it was time for me to board the regional train from Copenhagen to Roskilde. Joining me were hundreds of excited festival goers.

The festival is held south of the town of Roskilde, around 5 km away from the center and 35 km from Copenhagen. During the commute to the campsite, the atmosphere already feels electric—and slightly surreal. A significant part of this feeling comes from the comical amount of luggage everyone seems to carry.

As a reader, you would imagine that packing a hiking backpack or so would be enough in order to enjoy a music festival? Well, you will have to think again! In Roskilde, Denmark, I see hundreds of people, many looking like 16-year-olds, hauling ultra-packed dollies and IKEA bags. Speakers are pushed with shopping trolleys, while dozens of Tuborg 18-packs and various supplies are precariously stacked and creatively secured with gaffer tape, often appearing to exceed a person’s whole body weight (later, at the campsite, I would witness even funnier items, like someone deciding to bring an entire living room couch to the party—yes, an actual couch!).

On my way to the festival, I feel a stark contrast. There is this quiet Danish town, Roskilde, often described by people in Copenhagen as a boring place where nothing ever happens. Then, suddenly, a new group emerges: festival goers with luggage double their body weight, and everything mummified in gaffer tape (everyone seems to have adopted the same taping solutions , like an unspoken rule) to keep it together. A Scandinavian “Orderly Chaos”—everyone adopting the same pattern of behavior in embracing disruption, yet being remarkably creative in finding individualized solutions.

At the festival, already on the first day, the constant noise is striking, with little distinction between day and night. Besides the music stages, most of the parties will happen on the campsite, where groups of people organize themselves in camps and blast speakers from there. The several music sources overlap and morph into something indistinguishable.

But, as a volunteer, I’m fortunate to have been given access to a reserved camping area that is much quieter than the rest. Each of my volunteer shifts will last eight hours, covering both daytime and nighttime on four separate days of the festival week, intertwining with my“regular” festival experience. Surprisingly, having to set the alarm and having to be somewhere at a particular hour will integrate smoothly, otherwise, in a festival, most days might quickly feel like blending. I guess that losing track of time is another component of the “liberation” experience; in my case, I can feel the time passing and feel like I remain more grounded.

Being a major festival, Roskilde Festival’s calendar is packed. Besides the major artists who perform here every year, the festival offers a rich program featuring smaller artists, plus a couple of stages that host talks and workshops.

Fast-forwarding a few hours, a concert is in full swing. I’m standing at the back, where small groups of people are sitting on the ground, and there are lots of people around me drinking and talking. A girl and a boy appear to be having an argument, focused only on each other. They don’t notice the young woman picking up their used beer cups from the ground.

Across concerts, innovation panels, and a beer-soaked routine that blurs the boundaries between days, bottle collectors emerge as semi-invisible figures. They navigate the crowds with agility, collecting every bottle they can find. They seem serious and strategic in their work: knowing that crashed or broken objects have little to no value, they try to blow air back into the bottle or reshape crooked cans before adding them to their growing trash bags.

It is Day 1, and I am already struck by the sheer amount of trash and dirt everywhere. Part of the Orange Feeling seems to involve a quasi-hedonistic approach to living, where dealing with trash becomes something too dull to bother with: the empty beer can is simply left on the ground, so we can all move on.

This feeling is confirmed moments later: next to the stage, I meet Lars, a twenty-something-year-old who has been attending the festival for several years. When I tell him that I am trying to understand more about the role of the bottle collectors at the festival, it leaves an impression. He says that no one of his friends—no one—thinks about it, though he does. He acknowledges it as an issue but also believes that no one really thinks of it as being one. While the refund system was created to encourage consumers to be mindful of their trash, among some of the young Danes, there seems to be a sense that picking up bottles—eventheir own—and exchanging them is kind of shameful. Ironically, throwing it away becomes a status symbol. It’s an unspoken signal: I don’t need the money.

Picture from day 1 at Roskilde Festival 2024. Even though the gates have been open for less than 24 hours, the trash is already noticeable. There are only a few bottles lying around—the collectors must have picked them up already.

Sometime later, I speak with Marlene. Marlene is from Roskilde and is in her 50s. Roskilde Festival isn’t just for younger people; it also attracts a significant number of “veterans” who return year after year.

Indeed, Marlene has been attending the festival since the 1980s. When I bring up the topic of bottle collection, she reminisces about how, as a little girl, she would enter the festival grounds and collect beer cans to exchange. Back then, collecting bottles was something kids did to earn extra pocket money—a far cry from the situation today. Marlene recognizes that it is because of the festival’s growing size: maintaining that “community spirit” she fondly remembers is impossible in a temporary city of 130.000 people. She feels that something needs to change. About what, she is not sure.

While walking around the campsite, I spot a camp that decided to celebrate the drinking culture by using beer-related trash as their flag. Held in place by a few empty cans, a discarded Tuborg 18-pack plastic wrapper and a red 60L trash bag flutter in the wind.

Another thing you won’t often see in the marketing material is how much the weather can shape your festival experience—and in Denmark, it can make all the difference. The summer of 2024 brought rain and cold to the Roskilde Festival. At night, I shivered in my tent as temperatures unexpectedly dropped to 7–10°C. I think about how I would have never imagined being concerned about getting sick at a music festival in July.

Another implication is that while many describe the festival as notoriously dusty, this year’s downpours turned the grounds into a muddy hellscape. Rubber boots and raincoats became essential gear, with festival goers splashing through the flooded terrain, making the best of the soggy chaos. Amid this scene, I notice bottle collectors moving through the crowd. For protection, they use trash bags and whatever objects they can find. One man wears a makeshift plastic coat branded with the Copenhagen Metro logo, while most rely on scarves and muddy caps—likely scavenged from the ground. They are, too, festival goers, expected to rely on their own resources. I wonder how they are managing.

When I ask one of the bottle collectors about these struggles—I refer to him as Joe since he prefers to remain anonymous—he just shakes his head and keeps repeating, “It is shit, this year is shit.” We speak a mix of Italian and English: Joe currently lives in Italy and works at a pizzeria near Rome. He comes to the festival yearly “to make money” and puts in his hardest effort collecting bottles. On average, he earns 1 DKK (0,13 EUR) for every container or cup he gathers. For comparison, a dishwasher or restaurant worker in Denmark can expect to earn130–170 DKK per hour before taxes. To match that, since the refund is tax-free, Joe would need to collect around 75 items per hour—not counting the countless hours spent waiting in line to exchange them. When I ask if he manages to sleep despite the cold and the noise, he simply says he doesn’t sleep, only works—and laughs.

The stoic mentality of “it is what it is” is an invisible force that keeps a part of the festival’s waste cycle in motion. It is interesting to observe how, while the ‘Orange feeling’ is all about liberation, it seems to rely on a dynamic that is far from free. The festival’s carefree revelry depends in part on the relentless labor of others—a quiet contradiction in its ethos.

An overview of the deposit values for different items. While the Pant A, Pant B, Pant C system is the Danish nation-wide standard, Roskilde Festival introduced an internal deposit system—including assigning some sort of monetary compensation (0,2 DKK—equivalent of 0,03 €) for crushed up and foreign can, normally refused by the Pant machines.

Trash is treasure: Hanging out at the refund stations

Even though Roskilde Festival spans an impressive 2.500.000 square meters, and is estimatedto host 50.000 tents, there are only three refund stations, plus one Drop&Go refund machine. These refund stations are the main stage of my volunteering experience supporting the bottle collectors. The work is relatively centralized since everyone collecting will need to come by one of these three refund stations, sooner or later, to have their containers exchanged. As a result, I feel like I am quickly getting acquainted with the collectors’ community.

Day 1 is still a quiet night for the “West City” refund station—the furthest one, located about a 30-minute walk from the festival’s music area.

Surprisingly, the refund stations operate manually. The operations are run by youth associations and volunteers as young as 17 years old. They count and sort the deposits manually, then upload the money digitally to the user’s wristband. While these stations are open to everyone, in practice, they primarily serve the bottle collectors.

The refund stations have adjusted their opening hours over the years. While they used to stay open until dawn, in 2024, “West City” and “Agora L” operated daily from 08:00 to 02:00, while “East City” was open from 10:00 to 04:00. This significantly impacts the workday of the collectors: daytime tends to be relatively quiet, but the nights are intense, with everyone rushing to make their exchange before the station closes, trying to maximize the “best hours.” As the festival progresses, the volume of bottles, aluminum cans, and other refundable items grows larger and larger, and the handling time for every person increases proportionally—the more containers to count, the longer it takes, especially as the counting process is entirely manual. Dollies and baby strollers are popular tools for maximizing the number of bottles a collector can carry, and gaffer tape makes a reappearance—this time securing cans for transport, just as it held supplies together on the way to the festival. Midway through the festival, people typically faced a 4-6 hour wait to have their refunds counted—a necessary step before heading back “on the field” to start the process all over again.

The festival offers numerous volunteering opportunities for those eager to contribute in various ways. Earlier in the text, I mentioned my decision to volunteer to get closer to the bottle collectors‘ experience. I owe most of my contact to the social project “Responsible Refund,” a grassroots volunteer initiative aiming to help and celebrate the refund collectors during the festival. Through Responsible Refund, I was engaged as an “intercultural mediator.” Based at the refund stations, my role involved spending time there, assisting the bottle collectors queuing with any questions they might have, and managing potential conflicts. This was a support role distinct from that of a security guard or an info point representative. The project’s vision was to bridge the often-overlooked communication gap between refund stations and collectors. Refund stations were responsible solely for counting bottles and were not expected to consider the challenging and messy conditions in which collectors worked or the specific needs they might have.

But what happens to all these items after they’re handed over? On the final day, after a week of music, mud, and refund items, I speak with Janne, a 25-year-old student and a team leader in one of the refund stations. He explains that while products with the Danish standard refundlabels ‘Pant A,’ ‘Pant B,’ ‘Pant C’ are picked up daily—entering into the nationwide machine of Dansk Retursystem—the festival-specific bottles and cups are sent to a washing facility to be cleaned and reused the following year. The categories of items that neither hold a depositoutside the festival nor can be reused— like crushed bottles or foreign beers—are simplygathered and sent to the trash recycling system. However, at Roskilde, these items have a refund value priced at 0,2 DKK (in EUR, 3 cents), which is pretty much irrelevant to the business-minded collectors (and understandably so). I don’t see any of these items in the red refund bags at the back of the stations.

“Behind the scenes” at a refund station. On the left: each item is counted and sorted into a bag by category. On the right: full trash bags are piled up in the back, waiting for the daily truck pickup.

Janne takes pride in the impact of the refund stations. They processed 2 million refund items in 2024, 2.9 million the year before. I try to picture 2 million beer bottles in my mind, buthow can I? It just feels like too much.

Imagine this site without bottle collectors. As festival-goers drink and scatter their cups around like farmers planting crops, the discarded items would simply pile up, turning the grounds into an even trashier—and perhaps entirely unmanageable—landscape.

The flow of capital is equally striking. While many collectors prefer not to disclose their earnings, word on the street claims someone made 50,000 DKK (around 6,700 €) net in just one week. But don’t take my word for it—let’s break it down. To earn 50,000 DKK, they would need to make an average of 7,100 DKK daily, collecting about 700 items per hour over a 10-hour, non-stop workday. That’s roughly 11 items every single minute. While this figure seems highly unrealistic, it highlights how the blurry promise of “good money” persuades bottle collectors that it’s all worth it.

An average shift is generally quiet. The queue moves slowly as collectors sit on broken camping chairs, smoking and waiting their turn. At night, many huddle by the wooden structure of the refund station for shelter, dozing off on the damp ground. When their turn comes, someone in line wakes them, following what seems to be an unspoken rule of mutual solidarity.

View of a refund station during the day.

A “village feeling” lingers in the air—almost no one comes alone. Many collectors, like Joe, return year after year, often residing nearby in the Copenhagen area. I speak with Prince, originally from Ghana but now an Italian resident, who expresses his frustration. It’s his first time at the festival, lured by the promise of “good money,” but he finds the competition overwhelming. “The Romanians take everything,” he complains.

He refers to Romani families, who are a dominant presence among collectors. Tensions simmer between the African and Romani groups, fueled by accusations of breaking unspoken rules, such as waiting in line. The stakes are high—for the Romani, many have told me that this income can support their families in Romania for months. They often push boundaries, cutting in line with fresh bags of bottles while another family member holds their spot. These moments of conflict highlight the importance, for me, of having mediators present, ready to step in when the tone becomes heated.

People sleep, smoke, and chat in their circles of crooked camping chairs, as the festival swirls around them. Their “Invisible” presence is an essential part of the festival environment. Surviving on the fringes, they are, in many ways, the unrecognized dustmen of the ‘Orange feeling.’

Outro: the many faces of the refund system

Festivals can serve as a window to the future; each edition is slightly different, showing that change is both possible and necessary. These values have shaped Roskilde Festival’s brand, but as my week at Roskilde Festival unfolds, its contradictions become impossible to ignore.

Of course, Roskilde Festival’s organizers are well aware of its environmental sustainability issues. According to Statista, Denmark recently ranked as the top waste producer per capita in Europe, at 787 kilograms per inhabitant—so perhaps it makes sense to think that consumerism is engrained in the country’s culture. At Roskilde, the impact of individual behavior even exceeds the impact of the festival’s production: according to reports, this campsite waste makes up 75% of the total volume of 2,2 thousand tons of trash generated by the festival. Currently, it is common practice for festival goers to leave behind large amounts of personal belongings, including their tents, on the site; it constitutes a mass of unrecyclablewastse that can only end up at the nearest incineration plant.

There are already plenty of case studies and research available online about Roskilde Festival optimal waste management; the real challenge lies in changing the underlying culture. Roskilde Festival’s current attitude towards consumerism focuses on “influencing behaviorand inspiring.” Some of the initiatives that the festival has been taking in recent years have included a dedicated page on environmental responsibility (among others) on its website, the creation of a “Circular Lab” to provide a PR platform to circularity-focused startups, and the establishment of eco-conscious campsite communities—“Leave No Trace Camp,” “CleanOut Loud Camp” and, starting in 2022, “Common Ground”—where people would access through an application process.

POV: You are entering the Circular Lab. As the sign suggests, a “green future” awaits you behind the gate—and you are expected to participate actively in it.

Nevertheless, these communities, which create a sort of counterculture within the festival, remain a minority. The event primarily relies on its own grand cleaning machine activated in the last few days, with trucks and heavy machinery going around the campsite. And it moves swiftly: on July 19th, less than two weeks after the festival closed, I visited the site, and everything was spotless.

It is also worth commenting on how the management appears to acknowledge the presence of bottle collectors, as the refund stations’ operations are designed to accommodate the collectors’ workflow rather than focusing solely on individual customers. Despite that, no meaningful “benefits” are provided. For example, providing a quieter resting area for bottle collectors—something that already happens for the festival volunteers—could be a positive step. Currently, they are left to sleep at the main campsite.

A glimpse of waste management at the festival.

At the end of the day, the systems and structures that festivals rely on are shaped by their surroundings, meaning festivals often reflect the same systemic problems as society at large. It is fascinating to observe the behavioral differences festivals can inspire and to consider which behaviors are—or aren’t—supported by their specific systems.

Trash is a significant issue at the festival, one that the largely unacknowledged collectors play a crucial role in managing. The ‘Orange feeling’ thrives on the idea of freedom and community, yet it is built on contradictions. While festival-goers celebrate liberation, the invisible labor of bottle collectors plays an essential role in maintaining the festival’scleanliness and sustainability. Their overlooked efforts expose a deeper tension: the festival’s ethos relies on systems that marginalize those who sustain it.

Roskilde Festival might have grown to the point of benefiting from policy interventions, just like a real city. As it continues to navigate its complexities and strives to align more closely with its values, acknowledging and addressing these underlying dynamics could be the nextstep in aligning its ideals further with its reality.

Gallery of pictures from the last day and after closing

Trash is normalized: on their last day, a group of young girls hang out.

After the campsite closes on Sunday morning, the sheer amount of things left behind is astonishing.

On their last day, a group of young guys hangs out behind a fence creatively constructed from camping equipment and—you’ve guessed it—gaffer tape.

Waste after the festival closes. Above: Camp West. Below: Camp East.

This article was published under the Come Together journalism fellowship programme organized by Gerador. The article was originally published by Kurziv.