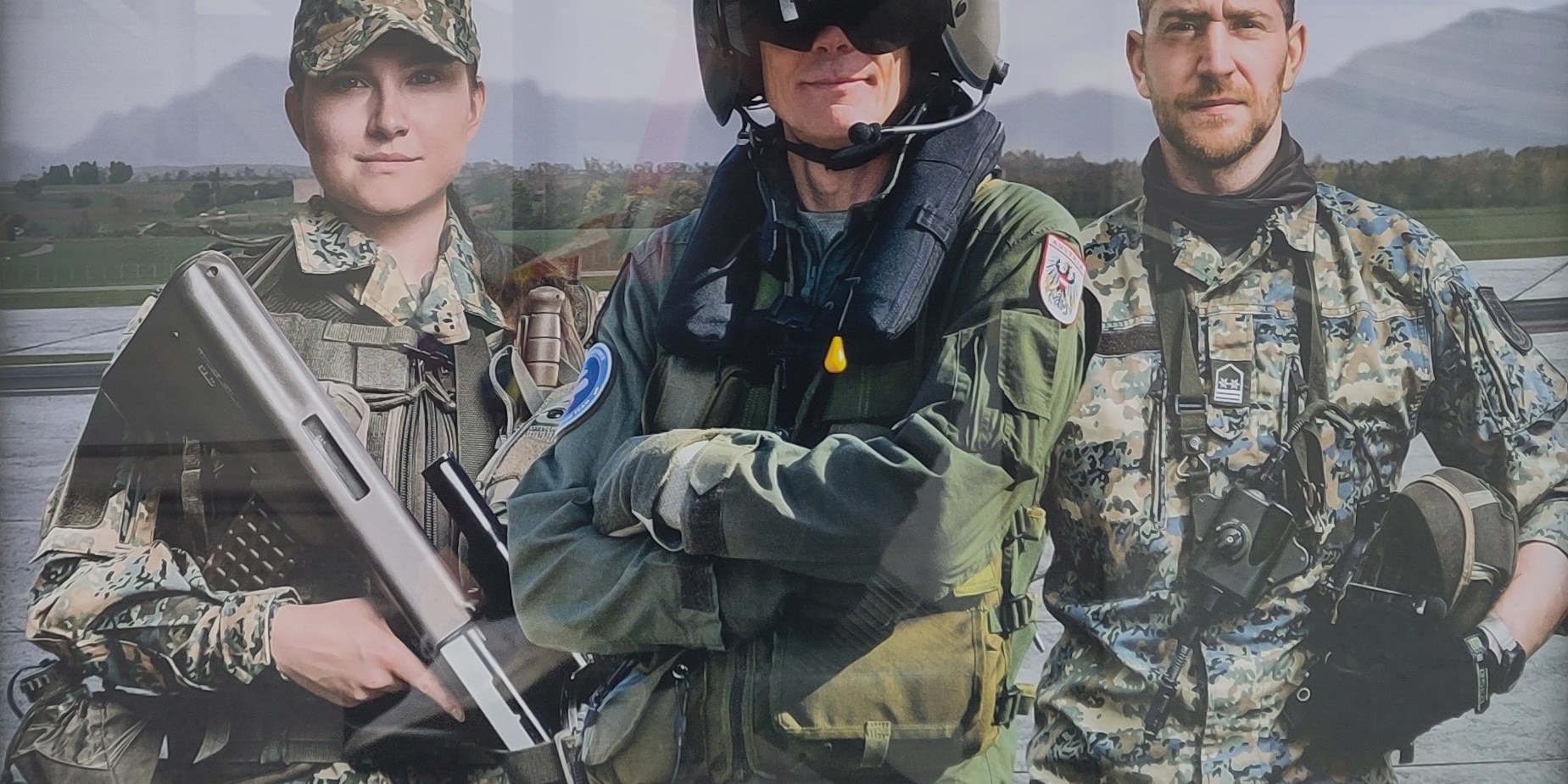

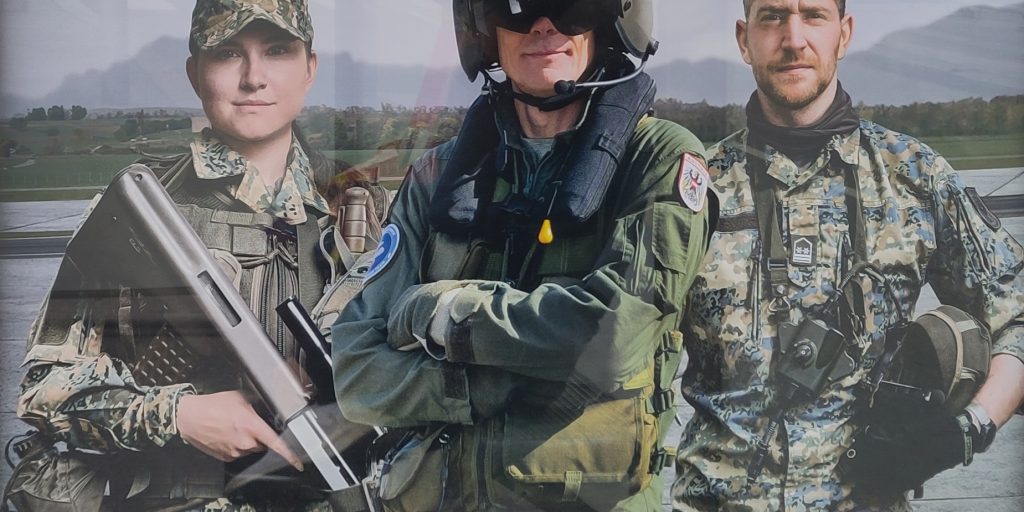

Bundesheer poster, Vienna, 30 November 2024. Image by Sarah Waring

The poster needed a double take: three action-ready figures dressed in fatigues could have easily been advertising a film rather than the Armed Forces. Having never seen military propaganda on the streets of neutral Austria, I took a quick reference photo. That was over six months ago when only outlying politicians were touting statements over European mobilization – before that is J. D. Vance lectured Europe that it should no longer rely on US defence.

Now European states are increasingly sparring over military spending. In circulating their ‘manifesto’ for de-escalation, former leading members of Germany’s SPD have challenged the collation government’s proposal to invest heavily in the Bundeswehr. Their warning against an ‘arms race’, advocating for a ‘gradual return to easing relations and cooperation with Russia’, smacks of remnant Ostpolitik despite failed trade relations with an openly imperialist adversary. ‘How anyone can even imagine closer cooperation with Russia at this stage is completely disconcerting,’ responded Boris Pistorius, SPD Defence Minister, during a visit to Kyiv.

Demilitarization or mobilization

Given political polarization, one would think that demilitarization and mobilization have little in common. And yet reading Nela Porobić Isaković’s stance against neoliberal armament alongside Angelina Kariakina and Nataliya Gumenyuk’s argument for autonomous enlistment provides a surprising parallel.

Both articles underline the failure of societies to recognize the agency of civilian women in war. Having lived through the Bosnian War, Porobić Isaković asserts, ‘there is the patriarchal assumption that it is masculine (and thus valued) to be the gun-wielding “protector”, and that women and other feminised groups are “victims” without agency (and thus devalued).’ Kariakina and Gumenyuk, reporting on Ukraine’s ongoing need for troops, observe how ‘recruitment communication targets potential conscripts, but families – wives, parents – often have the final say.’ Acknowledging the importance of matriarchal political agency flips the tradition gender roles that war otherwise perpetuates.

Overcoming silence

On a panel discussing how to avoid risks when documenting witness testaments at The Most Documented War symposium in Lviv last month, EUROCLIO advisor Nena Močnik spoke about contextual discrepancies. Having worked with survivors of sexual violence from the Bosnian War, she was asked to advise on documenting testimonies in Bucha, Ukraine. The intention was to learn from developmental practices cautious of retraumatizing witnesses, especially given the long-term lack of criminal proceedings in Bosnia and Herzegovina. ‘Transferring knowledge from one context to another doesn’t really work,’ said Močnik – her statement reflecting the symposium’s high level of candid discussion throughout.

According to Močnik, one aspect of witness communication that does translate, however, is silence. The moments when an interviewee doesn’t respond directly to a question can be the most telling: ‘Survivors of war crimes use silence to protect themselves and, therefore, it speaks very loudly’ – yet another reversal of the dominant perceptions of wartime agency, where a statement is considered evidential.

Speaking on a panel assessing documentary evidence’s role in seeking justice, Nataliya Gumenyuk also described alternative means of acknowledging trauma. The journalist is fully aware of her responsibility to witnesses: ‘Don’t steal people’s stories without writing about them,’ she warns. ‘The woman whose husband was tortured doesn’t expect his killer to be found but wants people to know what happened.’

Much of the symposium tackled how to maximise evidence in all its varied forms, expecting to find justice not just in the Hague but via varied forms of documentation. The Reckoning Project, involving Gumenyuk and Kariakina, which has filed a criminal complaint regarding torture in occupied Ukraine in the Republic of Argentina, shows just how seriously these journalists take international court proceedings. However, Gumenyuk also emphasizes the high value of delivering evidence that won’t reach a court of law by other means. Anecdotally, she recounts a lawyer who recognizes that their profession has its limitations: ‘books and films are better.’ And then Gumenyuk paraphrases Salman Rushdie from another event she participated in: ‘I’m not a victim anymore, he’s just a character in my book.’

Rejecting the illusion

Vital is not prematurely dramatizing war, however. Nena Močnik concerns regarding overcoming trauma acknowledge the importance of time passing. ‘Speaking of how to deal with recovery is difficult and risky, because we don’t know when the war will end and how,’ she said.

Equally important is not retreating into a fictional, protective bubble, pretending that Russia isn’t waging war in Europe. As Jaroslava Barbieri, co-author of the mobilization study informing Kariakina and Gumenyuk’s article, warns: ‘Today, Europe needs to have an honest and consistent conversation with its societies about the fact that war is already here, to reject the illusion that people are safe, and to finally abandon the old political strategies that tried to include Russia in the European security architecture.’