In the decades after the Second World War, many countries faced the challenge of rebuilding their housing and infrastructure while also having to accommodate a fast-arriving baby boom. The government of the Netherlands got more creative than most, putting money toward experimental housing projects starting in the late nineteen-sixties. Hoping to happen upon the next revolutionary form of dwelling, it ended up funding designs that, for the most part, strayed none too far from established patterns. Still, there were genuine outliers: by far the most daring proposal came from artist and sculptor Dries Kreijkamp: to build a whole neighborhood out of Bolwoningen, or “ball houses.”

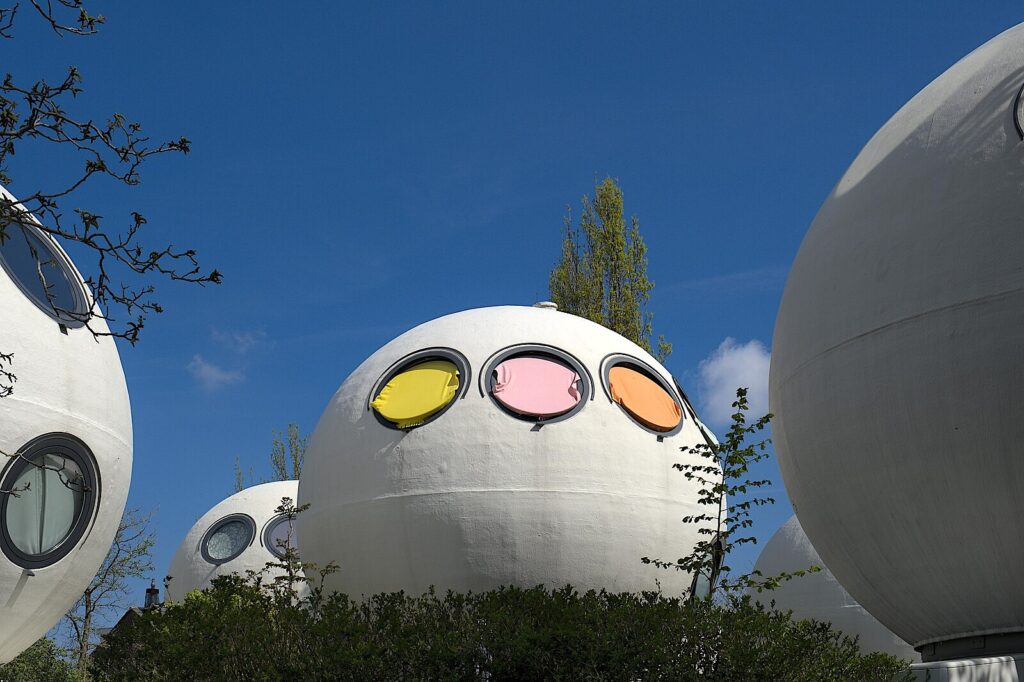

The idea may bring to mind Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes, which enjoyed a degree of utopian vogue in the nineteen-sixties and seventies. Like Fuller and most other visionaries, Kreijkamp labored under a certain monomania. His had to do with globes, “the most organic and natural shape possible. After all, roundness is everywhere: we live on a globe, and we’re born from a globe. The globe combines the biggest possible volume with the smallest possible surface area, so you need minimum material for it.” The 50 Bolwoningen built in ‘s‑Hertogenbosch, better known as Den Bosch, were quickly fabricated on-site out of glass fiber reinforced concrete. It wasn’t the polyester Kreijkamp had at first specified, but then, polyester wouldn’t have lasted 40 years.

Since they were put up in 1984, the Bolwoningen have been continuously inhabited. In the video at the top of the post, Youtuber Tom Scott pays a visit to one of them, whose occupant seems reasonably satisfied. (It seems they’re “cozy” in the wintertime.)

Like geodesic domes, their round walls make it difficult to use their theoretically generous interior space efficiently, at least without commissioning custom-made furniture; leaking windows are also a perennial problem. While each Bolwoning can comfortably house one or even two simple-living people, only the most utopia-minded would attempt to raise a family in one of them. As with other round or circular home designs, expansion would be physically impractical even if it were legally possible.

Used as social housing by the local government, the Bolwoningen now enjoy a protected historic status. (As well they might, given their connection with the art and industry of Dutch glassblowing: it was while working in a glass factory that Kreijkamp first began proselytizing for spheres.) And unlike most aesthetically radical housing developments, they haven’t gone to seed, but rather received the necessary maintenance over the decades. The result is an appealing neighborhood for those whose lifestyles are suited to its unusual structures and its contained bucolic setting, of which you can get an idea in the walking video tour just above. By the time Kreijkamp died in 2014, he perhaps felt a certain degree of regret that mass-produced globular homes didn’t prove to be the next big thing. But he did live to see the emergence of the “tiny house” movement, which should retroactively adopt him as one of its leading lights.

Related content:

The Life & Times of Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Dome: A Documentary

Goodbye to the Nakagin Capsule Tower, Tokyo’s Strangest and Most Utopian Apartment Building

The Utopian, Socialist Designs of Soviet Cities

Watch an Animated Buckminster Fuller Tell Studs Terkel All About “the Geodesic Life”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.