Since the Hamas attacks on 7 October 2023, Israel has been waging what is widely considered by legal experts, politicians and activists to be a genocidal war in Gaza. Official statistics estimate that 55,000 Palestinians have been killed and over 120,000 wounded in Gaza, in addition to the forced displacement of effectively the entire population. By late last year, Israel had already dropped 85,000 tons of (mostly US-provided) bombs on the territory: more than those used in World War II. Starvation is also a weapon in this war, following the complete blockade imposed by Israel since March 2025, and a denial even of World Food Program distribution of aid.

The collapse of the healthcare system and the contamination of water supplies has caused an unprecedented health crisis. The triangle of death – bombing, hunger and disease – threatens the lives of over a million people on a daily basis. In conjunction with the Israeli blockade, thousands of aid trucks are stalled at the gates of Gaza, prevented by the Egyptian authorities from entering through the Rafah crossing. Children, of course, suffer incommensurably. Not only is Gaza home to the largest group of child amputees anywhere, but as of early June, 2,700 young children suffer from acute malnutrition.

The sheer extent of murder and maiming makes it impossible to consider, and grieve, over each life that is destroyed. This is one aspect of the de-humanization of Palestinians. Occasionally, some especially harrowing report makes it into the international news circuit. One example is the case of the paediatrician Dr Alaa Al-Najjar, nine of whose ten children were killed by an Israeli airstrike, as was her husband (a fellow doctor). The diligent outreach of her relatives through the Italian media was on this occasion effective, facilitating the medical evacuation of Al-Najjar and her son Adam to Milan alongside dozens of other Palestinians.

All Palestinians, not only Gazans, are affected by this war. Israel has killed 943 Palestinians in the West Bank since 7 October 2023. Often through violence unleashed by settlers, Israel’s project in the West Bank seems to one of constant annexation, such that it recreates the facts on the ground, as it has in Gaza. Israeli officials are not shy about this wildly expansionist plan. At the time of writing, just as Israel has opened another offensive war front with Iran, it has also placed the West Bank under lockdown.

Gaza, January 2025. Image: Jaber Jehad Badwan / Wikimedia Commons

Inside Israel, there is widespread support not just for the war in Gaza, but also for forcible expulsion of Palestinians. At the same time, however, protests against Netanyahu attest to divisions inside Israel and dissatisfaction with his prosecution of the war. Most obviously, Hamas has not been eliminated. Nor have all the hostages (those not killed by Israeli airstrikes) been returned.

But Israel continues to ignore international condemnation, even after the International Court of Justice ordered it to halt its violence. The now-extinct notion of a ‘rules-based international order’, of which the United Nations forms the liberal scaffolding, no longer appears as the potential saviour of Palestinian (or any) human life.

That we are still parsing the trajectory and implications of this genocide more than 20 months later is damning to all regional and international political players. But urgent moral, humanitarian, and political questions nevertheless remain. At stake, every day, is the immediate wellbeing of Palestinians in Gaza, and whether they will live or die. More difficult to chart, however, are the Palestinians’ political prospects, in both Gaza and across all the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

Global and regional politics: Complicity or impotence?

The obvious conclusion is that there is global responsibility to mitigate, at minimum, the humanitarian catastrophe in Gaza. But even where starvation and aid are concerned, the US remains Israel’s unshakable partner. Sidestepping the UN and all international (let alone Palestinian) aid distribution, the Gaza Humanitarian Fund (GHF) has been the disastrous American answer to starvation and siege. Run by military contractors, it has become the only entity dispensing vital food aid allowed by Israel to operate in the Strip. Even its previous Executive Director, a former US Navy SEAL, resigned in objection to the impossibility of maintaining the ‘humanitarian principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence’. His replacement is a public relations and advertising executive, an evangelical Zionist pastor who does not hide his support for Israeli control of all of Palestine, even supporting the American president’s ‘Gaza Riviera’ plan.

In what one Palestinian journalist has called a ‘grotesque theatre of cruelty’, the GHF has taken over aid distribution in Gaza, entrenching displacement by forcing starving Palestinians to walk long distances for food in the desert heat. In iterative chaotic scenes, dozens have been killed adjacent to the GHF aid distribution points. The GHF has been widely accused of the ‘weaponization’ and ‘militarization’ of food aid, and even the facilitation of ethnic cleansing. Yet the organization is still active. Curiously, the Yasir Abu Shabab gang has also emerged in nearby areas. The militia, which has a history of smuggling weapons and drugs, is widely understood to be operating under Israeli protection, including in its clashes with Hamas. At the same time, its presence reinforces Netanyahu’s narrative that Gaza is ungovernable and should not be ruled by Palestinians.

Given its historical alliance with Israel, the broad contours of the US position are not surprising. But other western nations (e.g. UK and Germany) have also continued to arm Israel. The response of the Arab states, meanwhile, has been non-existent, unless one includes Qatar’s and Egypt’s role as ‘mediators’ between the US/Israel and Hamas. The Arab League, largely defunct for decades, has offered little but inertia. There are few grounds for confidence in the success of its plan for the reconstruction of Gaza ($53 billion) and a transition to a new political phase after the war, which would end once all the hostages are released. According to the plan, the Strip would be ruled by a technocratic government, with Hamas removed from power but possibly participating in security alongside either Arab peacekeepers (Egypt, Jordan, the Gulf) or foreign troops.

The plan’s main flaw is, of course, that Israel and the United States have largely ignored it. Egypt and Jordan, on the other hand, have refused to participate in the US-Israeli ‘Gaza Riviera’ plan, which would involve the displacement of Gazans en masse. Like the annexation of more territory (in both the West Bank and Gaza), the displacement of Palestinians from Gaza has become a goal of the war, as Netanyahu repeatedly and openly admits. Arab countries broadly oppose this, for reasons of their own, as do regional and international organizations.

Hamas has been willing to discuss various iterations of the plan for a 60-day temporary truce proposed by President Trump’s envoy Steve Witkoff. In return, the militia is demanding a complete ceasefire and the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza. In pursuit of this aim, Hamas released American-IDF hostage Edan Alexander, but seems to have been duped, because there has been no ceasefire to speak of since. Netanyahu hinted in early June at progress in ceasefire negotiations, but the attention of both regional and global powers soon after turned to the Israel-Iran war, which began on 14 June 2025. It seems that Israel is, as usual, buying time to drive as many Palestinians from their homes as possible.

Global solidarity and dreams of statehood

The global solidarity movement has been an important dimension of the entire genocidal war in Gaza. This has been more prominent outside the Arab world, since almost all Arabs live under various degrees of dictatorship, armed conflict, or both. The movement includes protests at universities and, more recently, flotillas and convoys heading to Gaza in the hope of breaking the famine-inducing siege.

The latest attempt was the Sumud Qafilah (Solidarity Convoy), made up of some 1,000 Tunisians and 200 Algerians, as well as activists from Mauritania. After departing from Tunisia and crossing the Ras Jdir crossing with Libya, the convoy was stopped on 13 June before it could enter Egypt. Both the convoy and the Global March to Gaza, which it had been planning to join in Cairo, were attacked by Egyptian security forces, with activists turned back and deported. The notorious baltagiyya – thugs blessed if not sent by the Egyptian government – were also reported to have assaulted activists.

Even medical evacuees allowed by Israel to leave Gaza are extorted by Egyptian companies and forced to pay backbreaking fees on their perilous journey out. The world media has repeatedly reported that aid trucks stand dormant and useless at the border, not let in by the Egyptians until foodstuffs rot. The Egyptians, in turn, blame the Israelis. But Arab public opinion generally sees the Egyptian government as complicit with the Israeli blockade of Gaza, especially since 7 October.

Expressions of popular solidarity may have been what pushed Ireland, Norway, Slovenia and Spain to join Sweden in recognizing Palestinian statehood. France is also working with Saudi Arabia towards this goal. This shifting tide is not complete by any means, but it is a change that would have been hard to imagine even a few years ago. Another notable development has been the EU review of the bloc’s partnership agreement with Israel. Under the agreement, which entered into force in 2000, the EU and Israel agreed that their relationship should be based ‘on respect for human rights and democratic principles, which guide their domestic and international policy’. The Dutch Foreign Minister Kasper Veldkamp, who initiated the review, voiced alarm not only at the humanitarian situation in Gaza and the West Bank, but also at statements by members of the Israeli government about a permanent presence in parts of Gaza, Syria and Lebanon. Coming too late to prevent the destruction of Gaza, however, critics have described it as no more than ‘performative’.

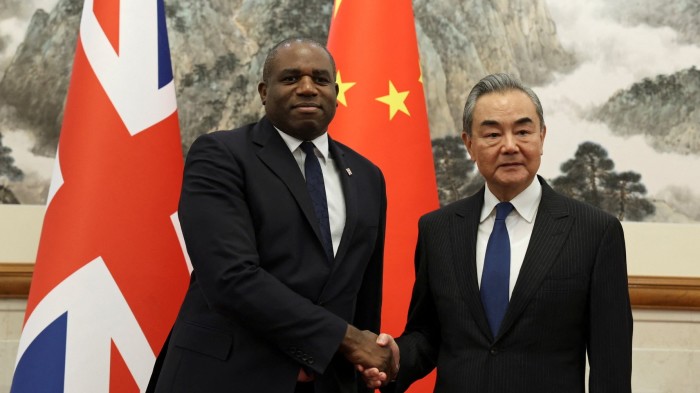

While the review cited ‘indications’ that Israel has violated the agreement, only Spain called for outright suspension of the agreement. This was to be expected, especially in the context of Israel’s current conflict with Iran. An EU that is divided over Ukraine will not suddenly arrive on the same page when it comes to Israel and Gaza. It is possible, however, that some parts of the agreement will be renegotiated. Even the United Kingdom has stalled talks on new trade agreements with Israel, and imposed sanctions on settlers in the West Bank. The British foreign secretary David Lammy’s unprecedentedly harsh language, which included direct criticism of Israel’s military operations in Gaza, may be paradoxical given British arms sales to Israel; yet the change is worth noting.

The relative dynamism of European diplomacy on Israel and Gaza is not, of course, mirrored by the US. The American ambassador to Israel, Mike Huckabee, has taken a stand that appears to deviate from the longstanding (though perpetually deferred) US pursuit of a two-state solution. Instead, Huckbee said, a Palestinian state might be declared on territory belonging to another Arab country. This astonishing suggestion is on par with Trump’s ‘Gaza Riviera’ plan, or the reported US negotiations with Libya to take in 1 million Palestinians forcibly displaced (ethnically cleansed) from Gaza.

Needless to say, none of these proposals presents a workable plan. The Americans know that. But the message is clear: no Palestinian state under Trump, just as there was no Palestinian state under Biden, or Obama before him, or George W. Bush before him. There have been suggestions that Israel’s latest expansion of the theatre of war might partly be an attempt to thwart a French-Saudi Arabian initiative for widespread recognition of a Palestinian state. A UN conference on the matter was indeed postponed after the strikes on Iran.

Palestinian divisions

Both regional and global momentum for a ceasefire in Gaza, and even for statehood, would likely be stronger were Palestinian political factions not themselves divided. This has been an ongoing problem since at least the 1993 Oslo Accords.

In January 2025, Hamas (the Islamic Resistance Movement based in Gaza) invited Fatah (the faction dominating the internationally recognized Palestinian Liberation Organization, based in Ramallah) to form a ‘community support committee’ that would oversee the administration of the Gaza Strip. Apparently motivated by a number of Palestinian initiatives and proposals, Hamas expressed the hope that Fatah would agree to collaborate within the framework of national consensus.

Hamas endorsed proposals by Egypt, which has offered to mediate between the two groups, to form a government of technocrats. In this, Egypt has the support of many Arab and Islamic countries. A community support committee would manage the affairs of Gaza temporarily within the framework of a Palestinian presidential decree. Hamas has announced it is ready to implement any agreements reached nationally and is open to any formula that would unite the Palestinians and their institutions. The Egyptian plan comes after several previous attempts at mediation and reconciliation, and tentative agreements reached in Egypt, Algeria, Russia and China to realize Palestinian-Palestinian unity. In each case, however, the President of the PLO refused to ratify the initial deals.

One might think that the genocide in Gaza would have made the seemingly impossible possible. But Israel’s onslaught has deepened the chasm between Fatah and Hamas, rather than bringing them closer. The context here is mounting criticism of Hamas, which has unsurprisingly intensified in Palestine and Arab quarters as a consequence of the colossal Palestinian losses and destruction in Gaza. Mahmoud Abbas is exploiting this situation by seeking to accelerate PLO reforms that he has previously rejected or avoided for fear that they would be interpreted as compliance with external dictates. The Fatah message has become sharper and more forceful: a demand for Hamas to admit its failure and give up power. This has had a two-fold effect on Hamas. First, the group has been put on the defensive; second, tensions have been exacerbated within its ranks, between those who took part in the planning of the 7 October attacks and those who were forced to defend it after the fact.

The devastation of Gaza has also rekindled enmity between Fatah and Hamas on the issue of dealing with Israel as a fait accompli. This rivalry derives from the perennial conflict in the Arab world between secular-nationalist and conservative–Islamic movements. While the former have aspired to cast off the constraints of religion and tradition and to modernize society along western lines, the latter has railed against types of modernization that threaten Arabo-Islamic identity and the values upon which Arab societies (including Palestine) are based. Fatah describes the war not as a People’s war, but one that Hamas has brought upon the Palestinians, contrasting Hamas’s actions with the path the Palestinian Authority is trying to promote – that is: avoiding violent struggle in the pursuit of liberation or statehood. Hamas, in return, has repeatedly accused Fatah of delegitimizing the resistance against Israeli occupation, which it claims has helped justify the international definition of the ‘resistance’ as terrorism and reinforced the notion that political negotiations are the only legitimate way to end the conflict with Israel.

Abbas, widely despised even in Ramallah, is desperately trying to salvage whatever is left of his political career. Recently, he has begun taking steps aimed at demonstrating strength and presence. A mechanism has also been established for selecting a replacement for Abbas, who is ailing. In November 2024, the PLO president issued a decree regulating a handover of power to the speaker of the Palestinian National Council, when the times comes. He has also decided that elections would be held within 90 days should his post become vacant or should he become seriously ill. Additionally, Abbas has declared a general amnesty for all those expelled from Fatah, including Mohammed Dahlan and his followers in 2011, after claims that Dahlan had murdered Arafat. In late April 2025, Abbas appointed Hussein al-Sheikh as deputy chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization. The move was controversial because it was done single-handedly, not democratically.

Given both Palestinian fragmentation and the absence of a ceasefire, Hamas faces a tough choice. Life in Gaza is one of continuous devastation and suffering, without Arab, Muslim, UN or western relief of any kind. In all this horror, what is defeat? Is it the acceptance of a truce? Or the failure to get the relief into Gaza, whose people need it most? Presented with this dilemma, Hamas may be inclined to define victory in minimalist terms, namely denying the IDF its goal of destroying the group, and to prioritize saving Palestine for another day. But that means a united Palestine, not one divided into three fronts: Abbas and the Palestinian Authority; Dahlan, a UAE adviser and a rival of both Fatah and Hamas; and possibly Israel’s preference to rule Gaza; and Hamas, the last bastion of the Muslim Brotherhood.

Hamas is bleeding, with no political cover left. Even sympathizers are changing their discourse to avoid the wrath of the powers that be in Trump’s world of ‘bone crunching’ power relations. Its top leaders have been killed, while the only politics Hamas representatives in exile can play is via regional mediators, who have their own agendas, no matter how altruistic their rhetoric sounds. Tens of thousands of Hamas fighters have been killed and its arms supply routes are almost closed. In Lebanon, the debate now is about how to disarm Hezbollah, rather than about Hezbollah arming Hamas or others in the region. Iran’s influence and power is on the wane, having lost reliable figures among its proxies in the Middle East, most prominently the Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah. The current war with Israel, which may entail major destruction to Iran’s nuclear programme and military capabilities, will cause it to ‘retreat’ further from regional affairs.

These developments comprise a huge blow to Shiite political revival (and expansion) in a region experiencing Sunni buoyancy, with key Gulf states staging a charm offensive towards the returning Trump Administration. Syria’s former jihadist leaders, yesteryear’s morbid foe, have been rebranded as partners by the Gulf and the USA. True to Trump’s words, Syria has been given ‘a second chance’, after sanctions were lifted months after the fall of Assad. Syria’s newly inaugurated officialdom is in no mood to take up the cause of Gaza or Palestine, it seems.

Given these regional shakeups, Hamas’s ‘last man standing strategy’ may backfire if no one can stop Israel’s slaughtering of the Gazans – least of all the US, which will defend Netanyahu to the bitter end. Few hopes can be placed in the EU, whose policy towards Palestine is confused, its brightest spots coming from the actions and stands of individual member states, not as a unitary institution with coherent policies.

But this does not translate into victory for Israel. Global public opinion has swung and will never return to wholesale, blind support for the ‘only democracy in the Middle East’. Despite official denials, this appears to have sunk into the Israeli psyche. When a former Israeli PM states that the war is ‘without a purpose’, with ‘pointless Palestinian victims’, it is an admission that the war has become a burden on Israel’s image. Even if the toothless tiger that is the ICC fails to stop Netanyahu and his war, the symbolic weight of the international recognition of Israeli war crimes is significant in itself for many peoples in the region.

The dilemma facing Hamas is that, as the world shuts diplomacy in its face, diplomacy is its last remaining option. In fighting too many adversaries at once, without a single actor having its back, Hamas condemns Gaza to a state of permanent siege. Witkoff remains an important link. Negotiations with him may be the only realistic way of ending the suffering. No Arab parties have the power to do that. Note that Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohmmed Ben Salman convinced Trump to lift the sanctions on Syria, but not to rein in Netanyahu.

Building Palestinian–Palestinian trust away from ideological narrow-mindedness is the key. The loss of life and territory is a loss for Palestine, not just for Hamas or Fatah. By recruiting other Palestinians into a strategy of conflict resolution, Hamas may be able to gain credit for reopening the search for primarily humanitarian outcomes and relief, as well as for addressing the root causes of the conflict. Here it might enlist the support and participation of EU states such as Spain or Norway, which facilitated the Oslo agreements.

The paradox

The situation is paradoxical. Since 1948, Palestine has never been in a worse position. The relentless pounding of Gaza and its people, and the continued displacement of starved Gazans into smaller and smaller spaces are, for many if not most, a clear case of ongoing genocide. The Arabs will not save Gaza, that is clear. Intra-Palestinian political disagreements and the increasingly brazen land grabs by Israel in the West Bank suggest that Gaza’s future is politically decimated. Even outside Gaza, Palestinians have no political clout.

On the other hand, the ravages of this war have spurred global expressions of solidarity on an unprecedented scale. Since the crackdown on US university activists over the past year, the weight of this western solidarity seems to lie in Europe.

Unspeakable violence, death, starvation, displacement and trauma, combined with political paralysis (if not complicity) therefore coexist with a counter-movement. Speaking out against Israeli crimes in Gaza is not as taboo as it once was in the West. Diplomatic overtures to Palestine are on the rise. There is no longer European consensus on Israel. One can only hope that this paradox will eventually give rise to a political opportunity, vouched for by what remains of ‘global civil society’.

The question of Palestine will not go away. Gaza is destroyed, but not obliterated. It will be recorded in the history books that the Arabs, and the world, allowed a genocide to unfold and persist for more than 600 days while they sat aside and watched. Even a genocide cannot extinguish the dream of liberation from a colonial occupation. With every life lost in Gaza and the West Bank, Palestinian aspirations for self-determination and cultural identity grow. The gutting of Gaza and the resulting oppression – inherent in all colonialism, past and present – are exactly what keep alive dreams and stories of freedom.