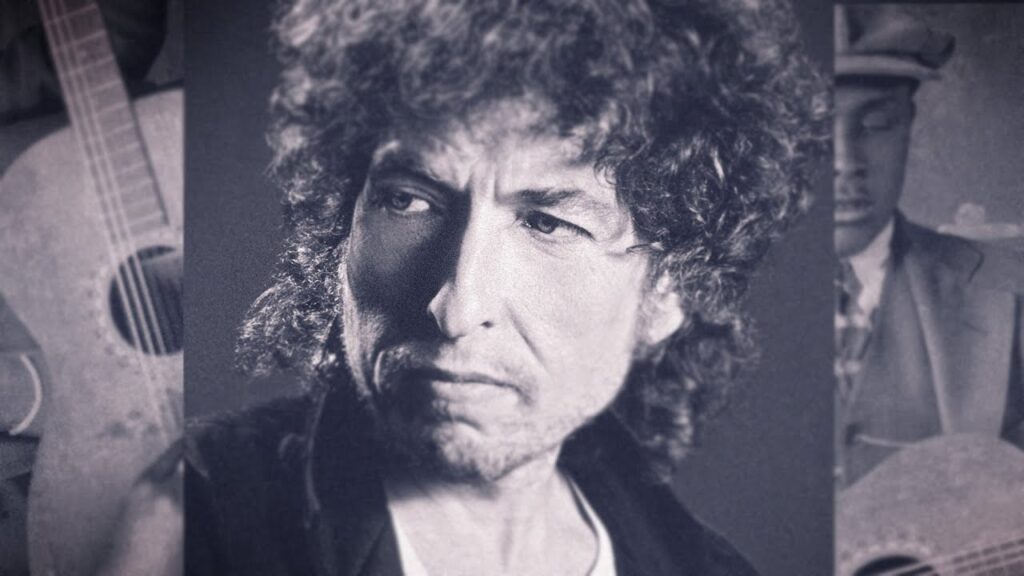

Most Dylanologists disagree about which is the single greatest song in Bob Dylan’s catalog, but few would deny “Blind Willie McTell” a place high in the running. It may come as a surprise — or, to those with a certain idea of Dylan and his fan base, the exact opposite of a surprise — to learn that that song is an outtake, recorded but never quite completed in the studio and available for years only in bootleg form. “Blind Willie McTell” was a product of the sessions for what would become Infidels. Released in 1983, that album was received as something of a return to form after the Christian-themed trilogy of Slow Train Coming, Saved, and Shot of Love that Dylan put out after being born again.

Of the material officially included on Infidels, the greatest impact was probably made by the album’s opener “Jokerman,” at least in the punk rendition Dylan performed on Late Night with David Letterman. Not that every Dylanologist is a fan of that song: in the Daily Maverick, Drew Forrest calls it “random and incoherent,” drawing an unfavorable comparison with “Blind Willie McTell,” which is “sure to be remembered as one of Dylan’s most perfect creations.”

The sources of that perfection are many, as explained by Noah Lefevre in the new, nearly 50-minute long Polyphonic video above on this “unreleased masterpiece,” whose origin and afterlife underscore how thoroughly Dylan inhabits the musical traditions from which he draws.

Like most major Dylan songs, “Blind Willie McTell” exists in several versions, but the one most listeners know (officially released in 1991, eight years after its recording) features Mark Knopfler on twelve-string guitar and Dylan himself on piano. Melodically based on the jazz standard “St. James Infirmary Blues” and named after a real, prolific musician from Georgia, its sparse music and lyrics manage to evoke a panoramic view encompassing the blues, the Bible, the ways of the old South, and indeed, the very history of American music and slavery. Though Dylan himself considered the song unfinished, he came around to see its value after hearing The Band work it into their show, and has by now performed it live himself more than 200 times — none, in adherence to the protean character of blues, folk, and jazz, quite the same as the last.

Related content:

A Massive 55-Hour Chronological Playlist of Bob Dylan Songs: Stream 763 Tracks

“Tangled Up in Blue”: Deciphering a Bob Dylan Masterpiece

How Bob Dylan Kept Reinventing His Songwriting Process, Breathing New Life Into His Music

How Bob Dylan Created a Musical & Literary World All His Own: Four Video Essays

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.