There has been quite a bit of discussion recently about how much (some) men apparently think about ancient Rome. Whether it’s the history of battles, the togas, the architectural feats survived by ruins spread throughout the Mediterranean basin, or the array of films from Ben-Hur and Spartacus to Gladiator and Gladiator II, some people seem particularly fascinated with ancient Rome. But recent and forthcoming films suggest that we might all benefit from spending more time thinking about ancient Greece.

The Return is a 2024 film adaptation of Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey, directed by Uberto Pasolini and starring Ralph Fiennes as Odysseus and Juliette Binoche as Penelope (in their first on-screen reunion since The English Patient). In addition, it was recently announced that Christopher Nolan’s next film will be an adaptation of The Odyssey, reportedly starring Matt Damon as the wayward Odysseus and Anne Hathaway as the homebound Penelope.

. . . works like The Odyssey have also formed who we are.

Though written nearly 3,000 years ago, Homer’s mythological account of Odysseus is well-known: We first encounter him in The Iliad as the king of Ithaca, who joins his fellow Greeks to wage war for ten years against the Trojans for their capture (or seduction) of Helen. Ultimately, Odysseus enables their victory through the deception of the wooden horse. Following their triumph, most of the Greeks return home, but as recounted in The Odyssey, that is not the fate of Odysseus and his men. He spends another ten years trying to get back to Ithaca, where his house is under siege from suitors who would marry his wife, Penelope, and kill his son, Telemachus.

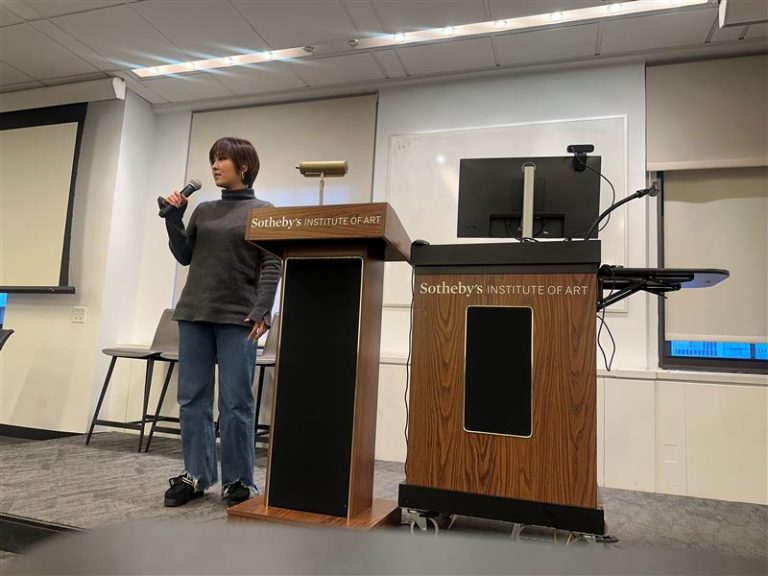

I’ve spent many hours thinking about Odysseus and his trials over this past year. The Odyssey was the Core Book at Wheaton College, where I teach undergraduate classes. The idea of the Core Book program is for the whole college community to read the same book (in addition to the Bible), engage in communal reflection and learning, and participate in on-campus events related to the book.

But this raises some rather pressing questions: Why should Christians bother reading works by non-Christians, including things written before Christ, especially when they are full of pagan gods, immoral heroes, and condoned violence? Why should we read this epic poem, whose protagonist is sometimes shrewd and self-sacrificial, but is also arrogant, duplicitous, and vengeful? Or, to put it rather bluntly, shouldn’t we just read our Bible? Over the years, I have found through discussions in both the classroom and the church that Christians sometimes want to read these kinds of books, but they’re not sure if they should read them and, if they do, how these works might relate to their faith.

Know Thyself

Reading books like The Odyssey (or The Iliad or Virgil’s Aeneid) might seem counterintuitive for followers of Christ, but pre-Christian works can actually help us to “know thyself,” as the ancient Greek proverb instructs us. The Odyssey is one of the oldest surviving works of literature, and it has shaped—and continues to shape—our collective imagination and cultural identity.

Throughout Homer’s poem, Odysseus and his men must constantly navigate dangers that are by now familiar to readers: the cave of the Cyclops, Poseidon’s rage, and the twin perils of Scylla and Charybdis. Even more familiar to us, though, are their desires for success, security, and love. When we first meet Odysseus, he is trapped on the lush island of the goddess Calypso. Though living in an apparent paradise, he longs for home: “Odysseus . . . was sitting by the shore as usual, sobbing in grief and pain; his heart was breaking. In tears he stared across the fruitless sea.” (5.81-84)

Of course, as Christians, our worldview is shaped primarily by God’s Word, which is the first and final authority for all matters of Christian faith and practice (i.e., our orthodoxy and our orthopraxy) and which continues to shape our culture in ways seen and unseen. Yet works like The Odyssey have also formed who we are. Reading these works helps us to understand our collective history and the broader cultural waters in which we swim. Not reading them only leads to collective amnesia.

A Universal Condition

In Emily Wilson’s excellent translation of The Odyssey, Odysseus is regularly referred to as “long-suffering” (3.84) for what he endures at the hands of others. For example, when he is finally allowed to leave Calypso’s island on a raft, he is confronted by a storm conjured by Poseidon: “More pain? How will it end? I am afraid the goddess spoke the truth: that I will have a sea of sufferings before I reach my homeland” (5.299-302). It’s not without reason that his journey is described as an “odyssey of pain” (5.340).

But it is also the case that Odysseus and his men are subject to the consequences of their own flaws and failures. For example, they could escape when they find themselves trapped in the cave of Polyphemus, the Cyclops, but Odysseus insists on staying to demand gifts from him, which leads to the deaths of several of his men (9-227-29). Later, when they have nearly returned to Ithaca, the men’s curiosity causes them to open a bag that is full of wind, which blows them back out to sea (10.47-49). Most tragically, on the island of Helius, the Sun God, the men eat the forbidden cattle while Odysseus sleeps (12.358). Like Moses descending from the mountain and hearing the sound of the Israelites worshiping the golden calf (Ex. 32:17-19), Odysseus smells the burning of meat: “My men did dreadful things while I was gone” (12.371-72). In response, Zeus destroys their ship, and all of the remaining men drown—except for one: Odysseus (12.414-17).

While reading The Odyssey with my classes this year, I was regularly surprised by the ways that this ancient poem spoke to our faith today.

Among the many things that have made The Odyssey so compelling across the centuries is its narrative full of imperfect characters who reveal the universal human condition of brokenness and the need for redemption. For some readers, Odysseus will be read as the victorious hero and king returning home to reclaim his rightful place. But for others, he will be seen as a deceitful, colonizing, and murdering adulterer. In truth, he is both. Characters like Odysseus reflect the complexity of what it means to be human. Though the setting and ancient narrative of The Odyssey are foreign to us, in many ways, its fallen world and flawed characters are all too familiar. Indeed, the Bible, too, presents us with a grand narrative full of imperfect heroes all in need of redemption—except for one.

A Man of Sorrows… and Hope

Spoiler alert: Odysseus makes it back home.

After twenty years of war and wandering, he eventually finds himself back in Ithaca: “I am here now. I suffered terribly for twenty years, and now I have come back to my own land” (21.206-08). But all is not well at home: his wife, Penelope, is tormented by suitors, who openly berate and threaten their son, Telemachus. After being disguised as a beggar by the goddess Athena, Odysseus sneaks back into his own home. In a dramatic moment, he reveals his identity to the suitors and Penelope when he shoots his own bow and arrow through twelve axe heads (21.422-24). What follows is a vengeful slaughter of all those who threatened Odysseus’s family and home.

Perhaps surprisingly, Odysseus might be read as an imperfect foreshadowing of Christ’s life and work. He is, after all, a long-suffering son who left his homeland (his father, Laertes, grieves the son who he believes has died), and he is described as a “man of sorrows” and rightful king whose return is promised (19.119). He even reveals himself to those who didn’t recognize him initially, echoing Christ’s appearance to Mary Magdalene in the garden (John 20:11-18) or to the two disciples on the road to Emmaus, who don’t know who he is at first (Luke 24:13-35). But it turns out that even when Odysseus does make it home through many dangers, toils, and snares, he cannot bring true restoration to his house and land. His gospel is not one of grace and peace.

Knowing the difference between a fictional character like Odysseus and the real person of Jesus Christ, who we declare as Lord and Savior, is crucial. But it is also the case that Christians throughout the church’s history have found God’s truth in unexpected places. Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215), for example, regarded Greek philosophy as “a stepping-stone to the philosophy which is according to Christ” (Stromata 6.8). Centuries later, Protestant reformer John Calvin (1509-64) similarly pointed to the possibility of finding God’s truth anywhere, even in pagan authors: “If we regard the Spirit of God as the sole fountain of truth, we shall neither reject the truth itself, nor despise it wherever it shall appear, unless we wish to dishonor the Spirit of God” (Institutes 2.2.15).

What stepping-stones might we, led by the Spirit, find in Homer’s text? Despite its ancient context and mythological genre, The Odyssey points us to two great truths that we can readily embrace as Christian readers:

- First, Odysseus reminds us that we all desire a homecoming in which relationships are restored, our home is at peace, and the table is set for a feast. It turns out that we have more in common with this figure from ancient Greek literature than we might have imagined. We all, like Odysseus, are on a journey home.

- Secondly, as Odysseus painfully demonstrates, the fulfilment of our universal need and our desired homecoming cannot be achieved through our own efforts. That kind of restoration can only come about through Jesus Christ, the true “man of sorrows” (Isa. 53:3), whose life, death, and resurrection brings complete, lasting peace.

While reading The Odyssey with my classes this year, I was regularly surprised by the ways that this ancient poem spoke to our faith today. True, none of us had battled against Troy or sailed across the sea while avoiding monsters. Yet Odysseus managed, despite his very apparent flaws and the fact that Homer wrote centuries before Jesus’ earthly life, to point us to Christ.

In his story, we found a companion on the way home.