academia will talk about decolonization

it will talk about it all the time

but with the exception of the few

it will not talk about your father, brothers, sisters, friends

those in cold trenches, decolonizing through de-occupation

that will not be epistemic enough to be discussed

Darya Tsymbaliuk, DO NOT DESPAIR. a letter to a scholar whose homeland will be attacked by Russia next

I am writing this in March 2024, two years after the start of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine and a year and a half after I was invited to speak as part of the Ukrainian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, which this year opens in mid-April. Right now, Andrii Dostliev and I are finishing a project which was commissioned for it, ‘Comfort Work’.

Despite the horrors of the war, 2022 also brought hope: hope that, by making a consolidated effort and partnering with like minded allies Ukrainian cultural professionals might be able to shift, shed light on and ultimately undermine the privilege and centrality of Russian culture.

As my colleagues and I have written in previous articles, the beginning of the war in February 2022 marked a turning point as Ukraine shifted from a post-colonial state to a decolonial one. Conversations in Venice were full of optimistic expectations of change, and many of the participants, I think, envisioned themselves as an active part of it.

I remember the moment at the beginning of the war when I realized that the reason why Ukrainian cultural representation in the world is so weak – here and elsewhere I use the word ‘Ukrainian’ in its civic and political, not ethnic dimension – is above all the lack of available platforms for public expression. The reality, however, turned out to be far more complex.

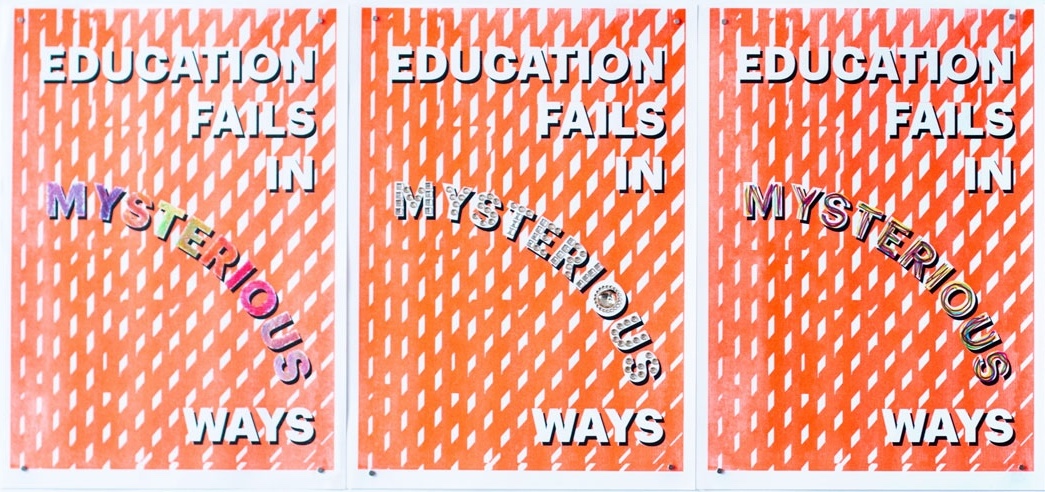

Andrii Dostliev, ‘Education fails in mysterious ways’, riso-type posters, 2023. Image courtesy of artist

As Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman write in their book The Empire of Trauma, the earthquake which levelled several Armenian cities in 1988, leaving tens of thousands dead and over a hundred thousand wounded, also became a politically significant event because ‘in practical terms, it gave the West its first opportunity to enter this region.’ Fassin and Rechtman attribute this to the fact that the Soviet world ‘had hitherto been firmly closed to all outside interference.’ However, over thirty years after the collapse of the USSR, residents of territories that were once forced to be part of it have repeatedly found that the attention of the West is extremely selective and not necessarily dependent on how open a country’s region is. A natural disaster or a war at home may indeed draw attention to the affected region for a short time – with global media outlets covering events as if they’ve just discovered your part of the world on the map. In 2014, when Russia occupied Crimea and parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, and then when the full-scale invasion began eight years later, the so-called collective West noticed Ukraine as if for the first time, somewhat surprised to realize that between Berlin (or, if you are very lucky, Warsaw) and Moscow lies not an endless and nameless wilderness but a territory with living people who have their own language and culture but whose homes are being destroyed as I write.

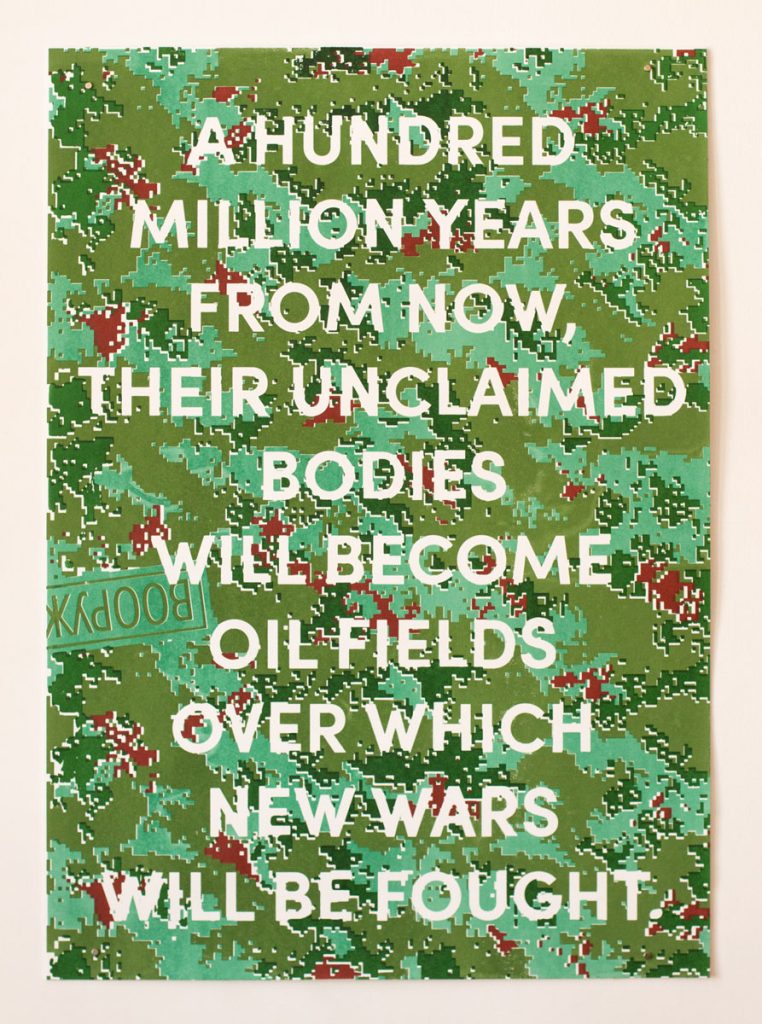

Andrii Dostliev, ‘Dead Pixels’, silkscreen poster, 2022. Image courtesy of artist

The consequence of your country being a part of traumatic geography on the Western mental map is a very specific form of attention and recognition that your society receives. The Oscar awarded to the film 20 Days in Mariupol by Mstyslav Chernov is a vivid example: it’s hard to imagine a Western director starting their speech with the words ‘I wish this film had never been made.’

The wave of interest in Ukrainian culture provoked by the full-scale invasion has undoubtedly led to the creation of new public platforms and opportunities to manifest Ukraine’s cultural presence. However, this attention has been given on rather rigid terms. It wasn’t because of a sudden realization that the wide range of cultural forms that exist within Ukraine are no less valuable than those of Russia or the West. This scrutiny comes with an embedded hierarchy and is a form of temporary solidarity with a community that is being physically destroyed by a stronger force. The cultural value of the product that was given public exposure – particularly at the beginning of the full-scale invasion – was therefore a secondary concern. The principal one was that its creators were from Ukraine and could be provided with cultural humanitarian aid.

As a result, we witnessed a surge in Ukraine-related events abroad which were often of poor artistic quality. They were organized by institutions that wanted to help but often lacked both the expertise to create a quality product and the ability to realize their shortfall. Exhibitions dedicated to Ukraine featured artists whose Ukrainian origin was the only thing they had in common, missing any clear curatorial message.

The flooding of these events into the cultural space blurred the boundaries between emergency residencies or exhibitions organized as a gesture of solidarity and professional, quality-based Ukrainian projects. Moreover, the temporary hype led cultural workers, some of whom had built their entire careers abroad, to be perceived as mere Ukrainian bodies, regardless of their professional level. They were seen as bearers of trauma and their activities framed exclusively in identity-based categories.

The apparent demand for quality Ukrainian art which ‘can do more than speak of war and act as a perpetual reminder of the urgency of the situation’ as opposed to art which fails to ‘override fixed and binary categories of identity’ excludes several very important things. Firstly, Ukrainian art which is expected to be ‘more than national’ and moves beyond ethnic dimension is framed in artificial categories of national identity primarily by critics’ descriptions, curators’ work, and the audience’s perception, which is a symptom of looking at Ukraine through the lens of colonial Russia (or, as in the case of Poland, conditioned by its own colonial past too). It is impossible to make ‘post-national’ art if those who look at it and those who describe it still perceive the work in terms of the author’s nationality and see its ‘Ukrainianness’ as its main characteristic.

Another problem with providing public platforms to represent Ukrainian culture in the West is that such platforms often create a ‘ghetto’ of sorts, where only Ukrainians (refugees or diaspora) and a few like-minded allies attend events dedicated to Ukraine. This format maintains the current colonial hierarchy: it signifies solidarity but lacks any emancipatory potential because it does not involve integration with a broader audience beyond the narrow pool of Ukrainian sympathizers, nor does it provide the possibility of real influence. The target audience for decolonial change simply don’t come, and a Ukrainian bubble therefore arises, where a space is formally provided for the representation of the ‘emotional and traumatized Ukrainian voice’, but that voice is not heard.

To the west of the Oder river, this smattering of charitable deeds was also a means of redemption: it’s easier to provide Ukrainian artists with space in an institution for a one-day event between planned exhibitions than to contemplate how decades, even centuries of focus on the culture of a neighbouring colonizer and the adoption of its gaze as default contributed to the normalization of Russia’s wars and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The proliferation of Ukraine-related decolonial events paradoxically serves as a substitute for real decolonial (read: structural) changes.

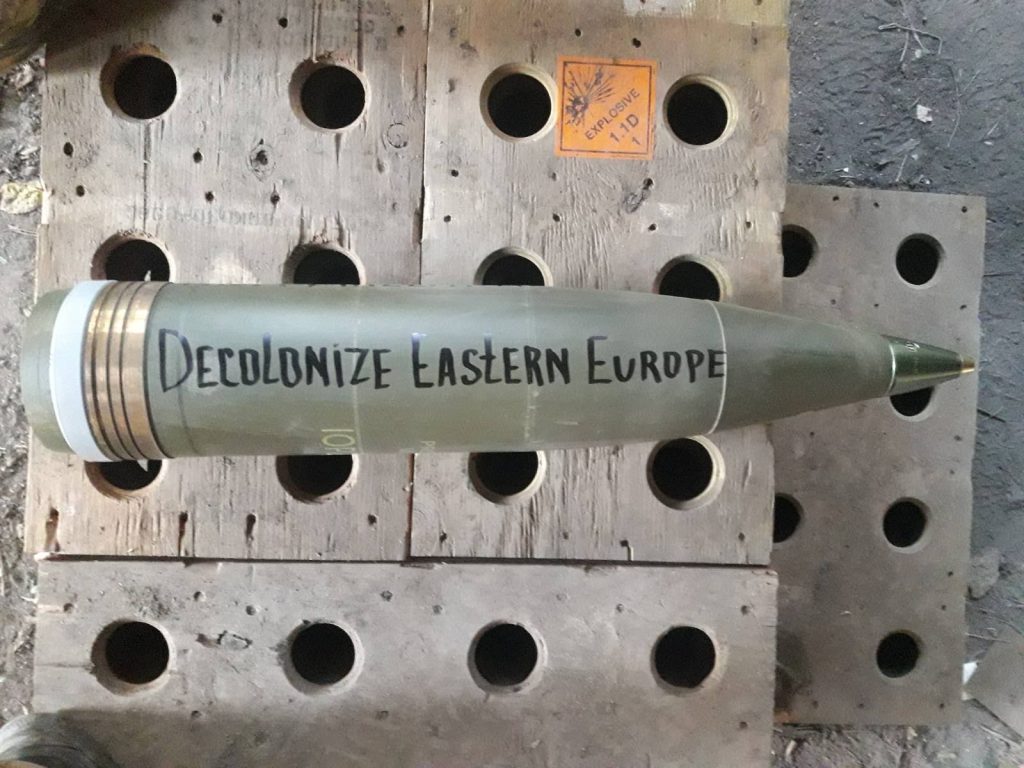

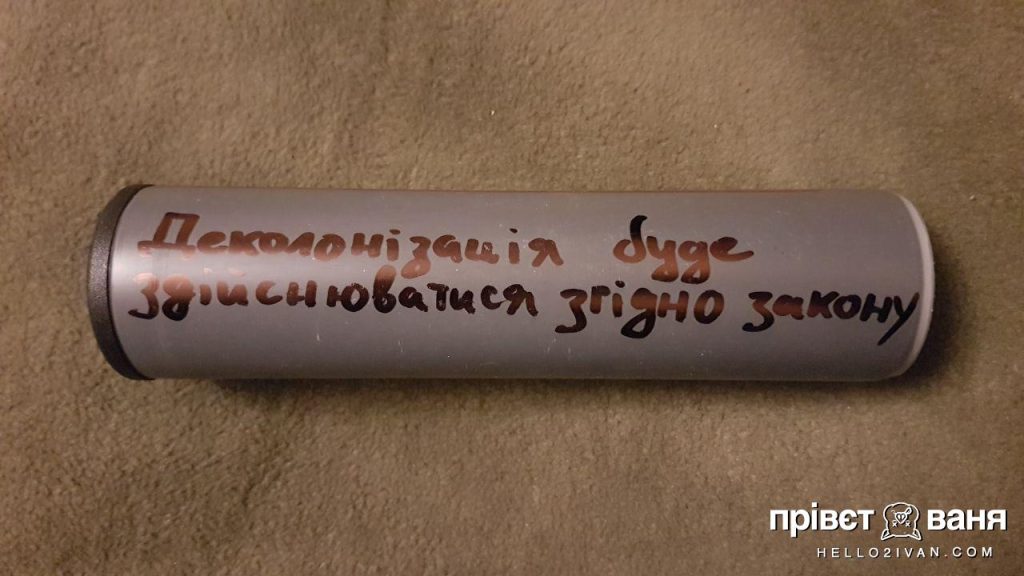

Andrii Dostliev, from ‘It’s decolonial‘ series, 2023. Images courtesy of artist

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, I have repeatedly found myself in situations where breaking the pattern of creating a ‘Ukrainian ghetto’ and the attendance of non-Ukrainians at Ukrainian events became a source of anxiety for Western hosts: ‘Who are these people in the audience? Do you know them? Are they your friends?’

Now, two years on, it can be argued that what we initially perceived as a shift towards decolonization was just a temporary Ukrainian quota with little potential for structural change. On the contrary, institutions – both in culture and academia – have mobilized existing resources to preserve their status quo, preparing to contest even the potential threat to their position of privilege.

Various strategies of appropriating the decolonial discourse and instrumentalizing it to preserve the existing colonial hierarchy can be cited here as examples. Marking the term ‘Russian culture’ as problematic has led many cultural figures who had built their professional identity in affiliation with it to unsubscribe from the symbolic space. Suddenly, everyone stopped being Russian, but continued to defend their professional right to speak on behalf of the entire region of the former Russian colonies. People who left Russia after 2022, having already built their careers there, suddenly stopped using the word ‘Russia’ in their bios and/or have discovered some relatives – always female: grandmothers or aunts, for some reason – in Ukraine or other former colonies, where they spent a lot of time as children, enjoying tasty national food and the pleasant sounds of a somewhat funny local language. [img. 5] Symbolically leaving the set of those targeted by the call to ‘decolonize Russian culture’, all these individuals began to consider themselves part of a community that will be now in charge of ‘decolonisation’ – or rather, the preservation of the existing colonial hierarchy, but this time in a decolonial wrapper. Western institutions supported this relabelling, readily providing a space for self-proclaimed ex-Russians to represent the entirety of a region which was once Russia’s empire.

Photos from the performance ‘Grandma from Zhytomyr’, Schinkel Pavilion, Berlin, 2024. Image courtesy of artist

The sudden search in one’s family ancestry for more oppressed heritage has nothing to do with actual decolonization through addressing colonial erasure or bringing back plurality. It is, in fact, the opposite of seeking decolonial justice: as long as the identity of a Russian curator – or any other public figure – provides privileged access to institutional resources, everyone is satisfied. Another problematic aspect of such shifts in identity is the understanding of one’s connection to the Ukrainian context in terms of ‘primitive ultranationalism’ – literally through blood and soil, which ignores the civic, social and political dimensions. From this perspective, belonging to a certain cultural community is something one is born into; it has nothing to do with conscious choice or the performative, everyday component of that culture, which is itself reduced to ethnic kitsch. We therefore have a peculiar paradox: the reappropriation of the colonized identity and the simultaneous preservation of the colonial gaze on this identity. (It is worth mentioning that Western researchers traditionally attribute ‘bad nationalism’ – monoethnic, monocultural, aggressive towards anything that is not its constituent – to formerly colonized nations that gained statehood.)

What should we then do? If Ukraine wants to keep alive the discussion about decolonial approaches – and I hope it does – we should focus, first and foremost, on creating new horizontal connections with representatives of other former colonized communities which have similar experiences of oppression. It is with them that, in my opinion, the Ukrainian cultural community should primarily engage and unite.

This essay was first published in Decolonising Art: Beyond the Obvious. Learn more about the publication here.