Curated by Sara Chyan—a jewellery designer, artist, alchemist of volatile materials, and coach on the Innovation programme at the Royal College of Art—the group exhibition Echoes of Presence was presented as part of London Craft Week 2025. Sara has long worked with thermally unstable metals like bismuth and gallium, cultivating an intuition for rupture and transformation. Within this thematically charged context, Lin Dong, working under the name Cloudslin, enters the scene not with declarations, but with hesitation. His triptych, Homing the Celestial Unseen, doesn’t depict a memory so much as it stages a crisis in return.

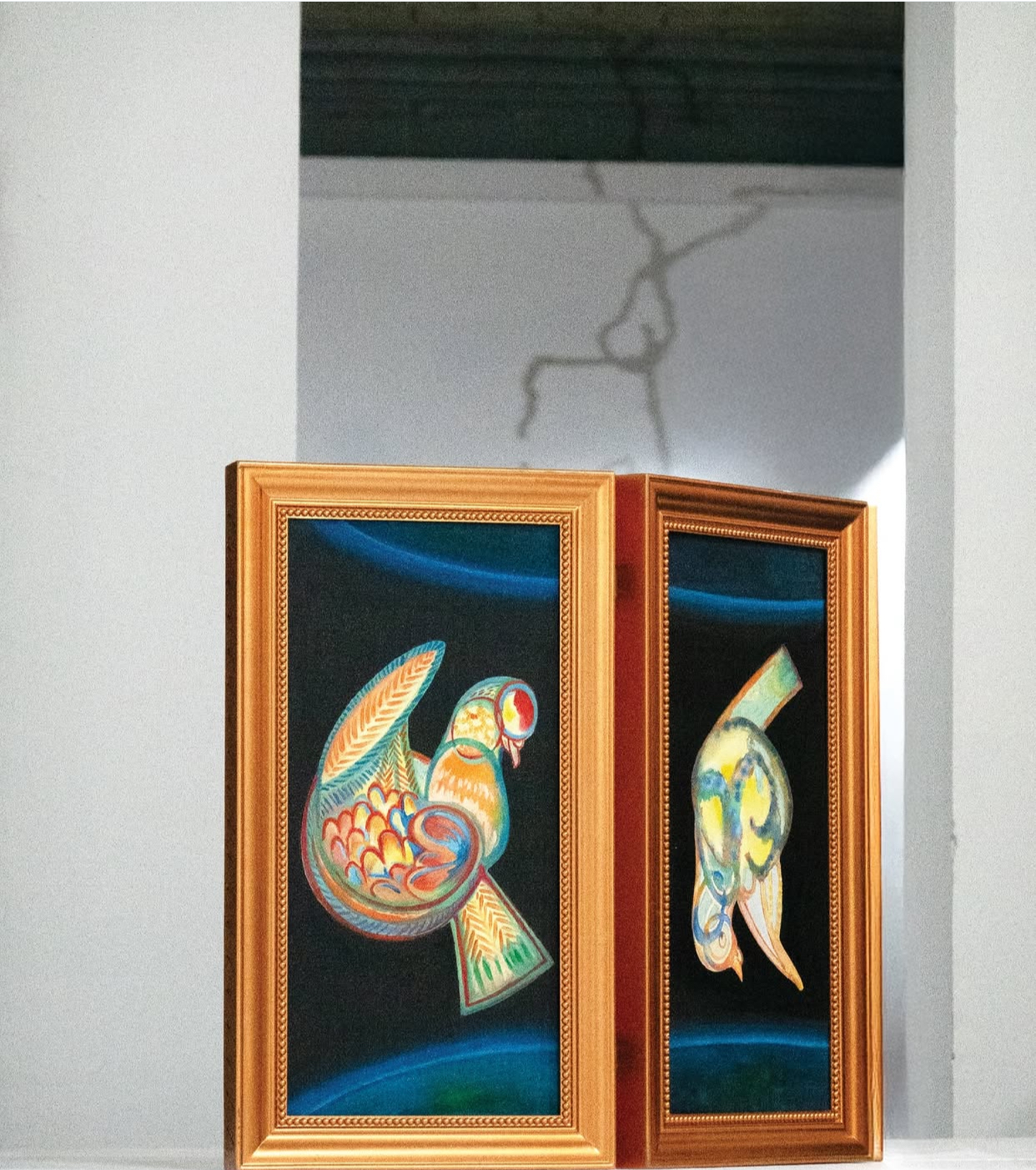

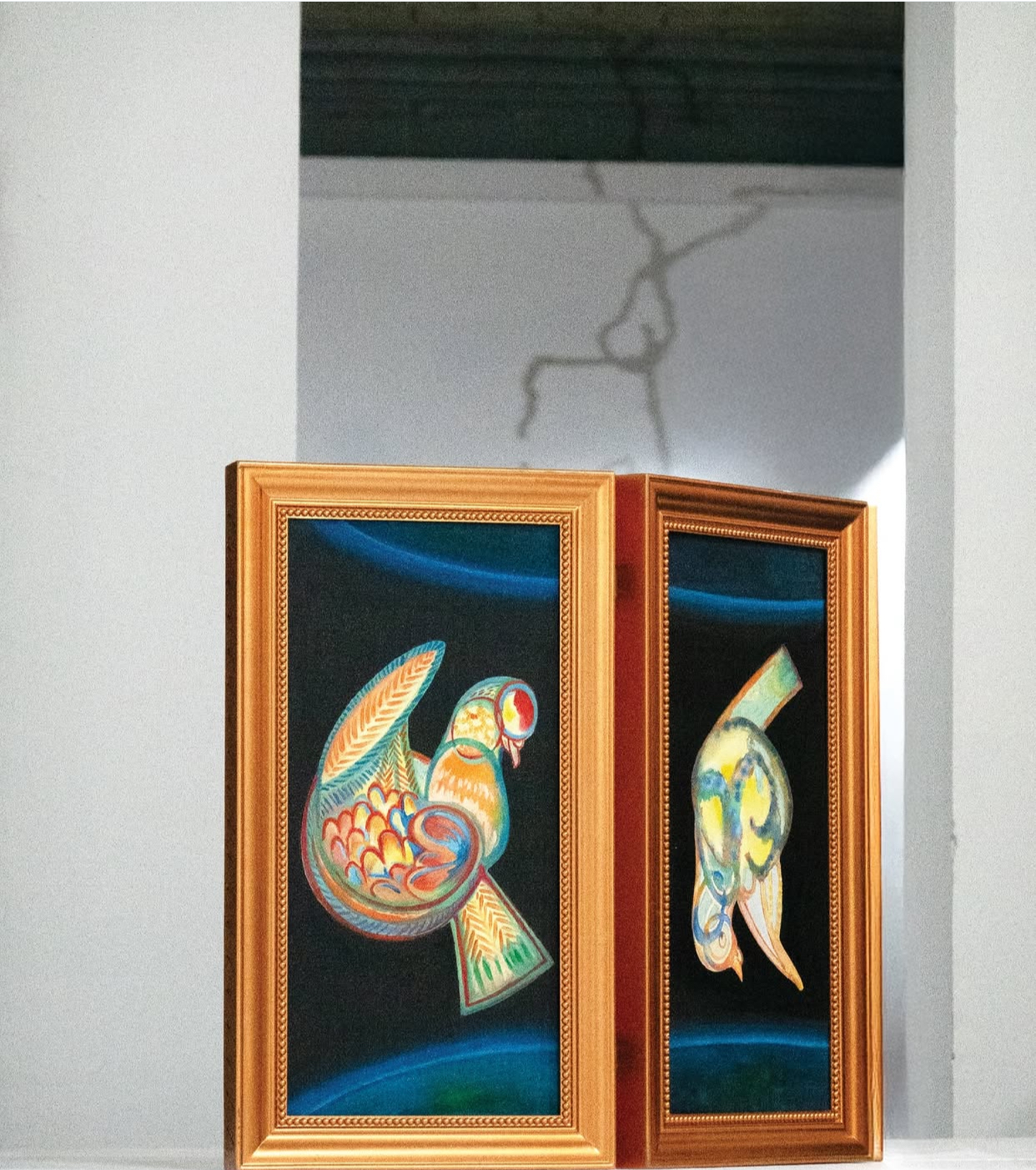

The structure of Cloudslin’s work suggests a familiarity we cannot quite place. A window. A mirror. A pigeon mid-flight. These aren’t metaphors, nor narrative cues. They’re residue—what remains when context collapses. The mirrored surfaces don’t reflect; they interrupt. They withhold. The viewer doesn’t encounter a story—they stumble into a delay. A refusal. In Lacanian terms, what appears to mirror is in fact a fissure. You don’t see yourself. You see where the image used to be—before the self was asked to perform.

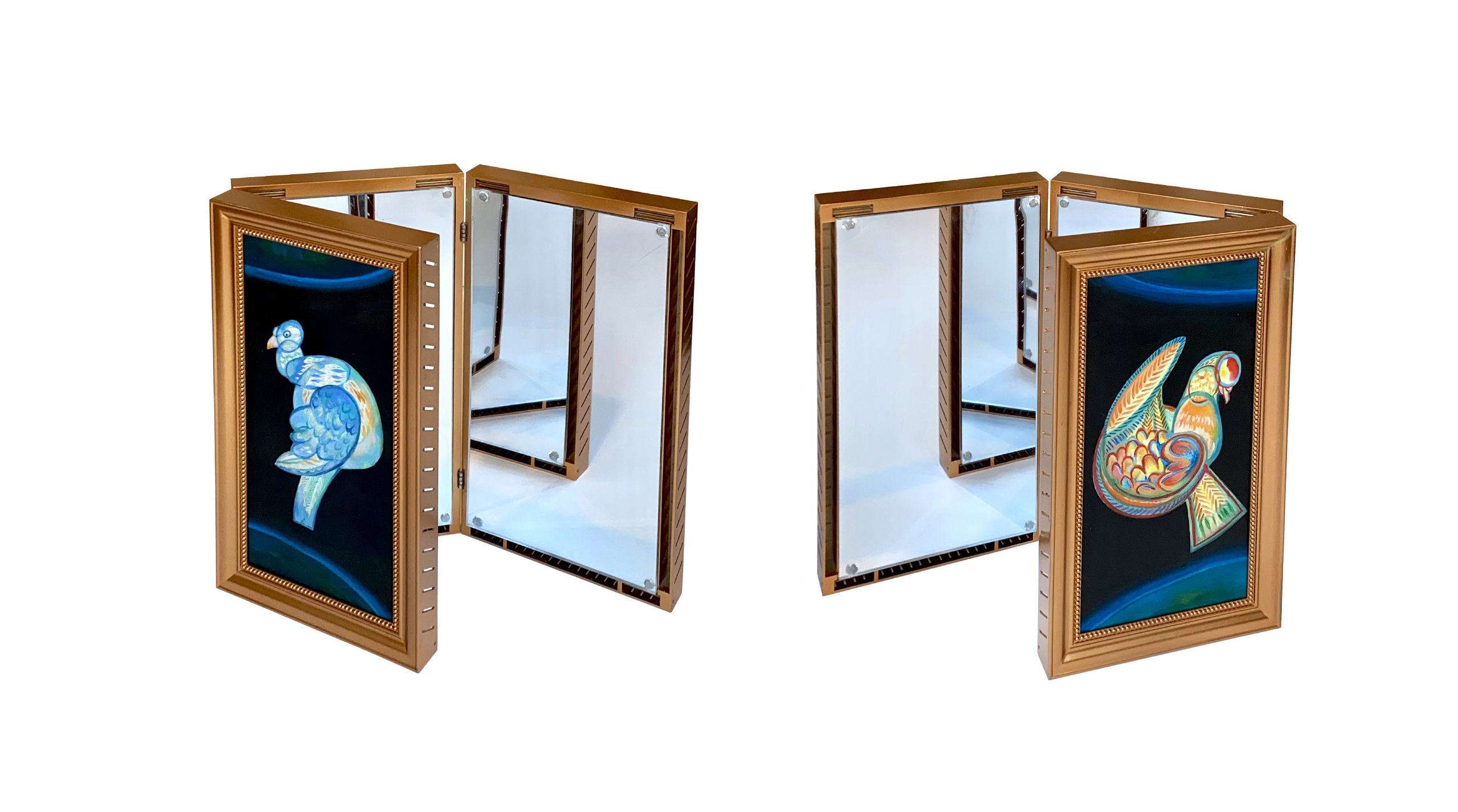

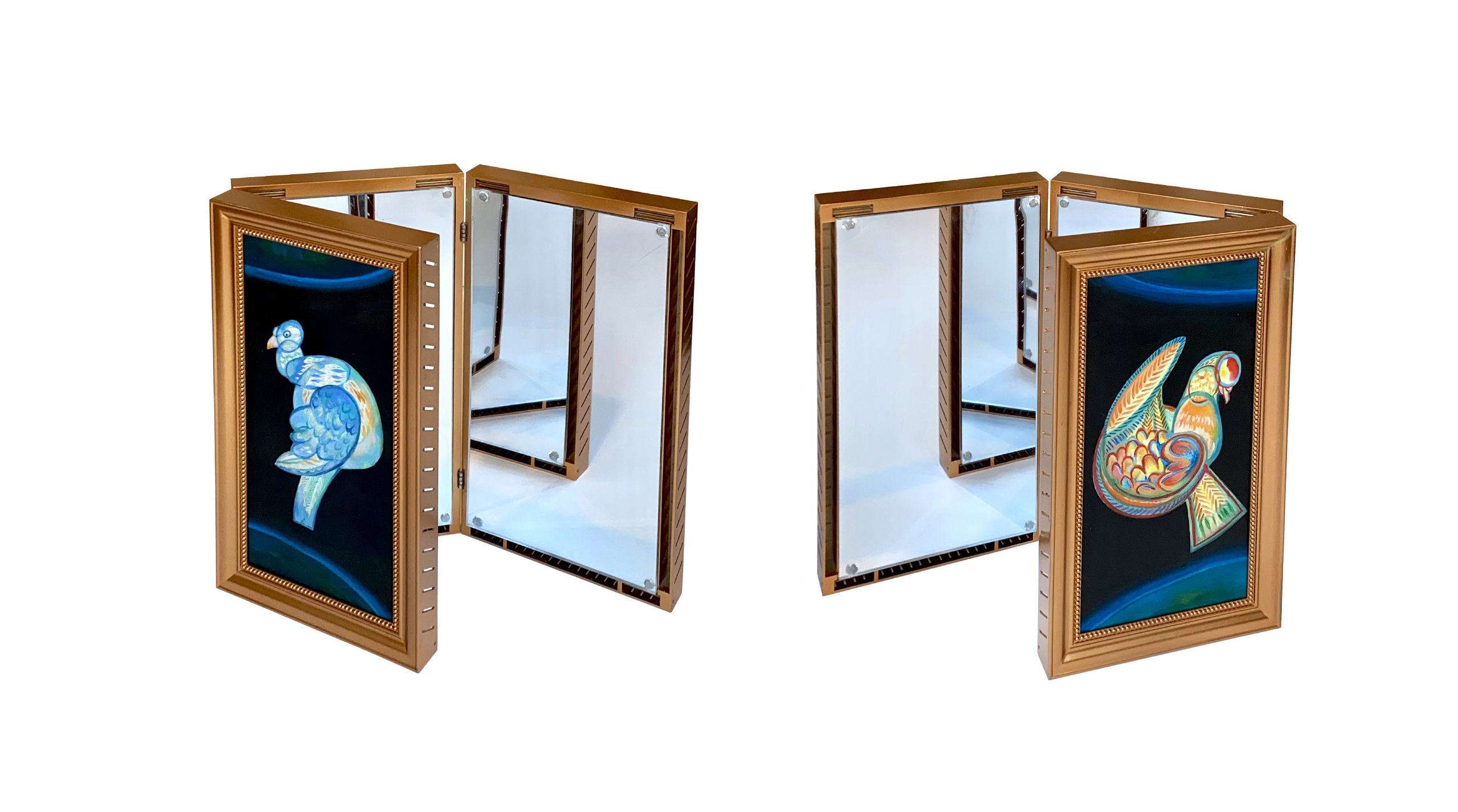

This triptych finds its roots in Lin’s years in Paris, where pigeons—messengers of the sky—drifted quietly through daily life. More than incidental, they became stand-ins for human presence: familiar yet distant, communal yet estranged. They populate the panels not as symbols but as interruptions—echoes of a shared yet unstable reality. The first iteration of the work was executed in watercolor, interweaving Dunhuang-inspired motifs and Miao textile palettes with washes of color that bleed and settle. Reimagined later in oil, each bird now emerges from a shadowy, ambiguous field. A curved band of blue arcs across the triptych, evoking a cosmic pull—part memory, part longing—for what remains out of reach.

Anchoring the work is its frame: a meticulously 3D-printed construction modeled after the gilded mirrors and windows of Lin’s Paris apartment, where reflection—both literal and emotional—was woven into daily life. This is no decorative border; it’s structural thought. On the back, a mirrored surface folds the viewer into the act of looking, blurring observer and image. The object becomes recursive: shaped by private domestic memory, inscribed with Chinese antiquity ornamental language, and built around a conceptual architecture of rupture and self-inspection. When unfolded, the triptych doesn’t narrate—it suspends. It opens not outward, but inward, like a portal carved inside the habitual.

The initial draft was rendered in watercolor, blending traditional Chinese ethnic motifs, including patterns from Dunhuang murals and Miao textile palettes. These forms were later reimagined in oil paint on canvas, where the background palette subtly channels a longing for distant family and a quiet confrontation with the unknown cosmos. The work does not recall memory as narrative—it compresses memory as form, layering displacement into surface tension.

The central panel, a dense black void, doesn’t mourn. It absorbs. A curved incision cuts across the dark, echoing Francis Bacon’s spatial violences—yet where Bacon wounded flesh, Lin incises awareness.

(For visual reference, see Francis Bacon’s Study for Portrait VIII (1953): https://www.francis-bacon.com/artworks/paintings/study-portrait-viii

From this scar emerge pigeons, their bodies assembled not from abstraction, but from lived repetition. They aren’t symbols of peace. They’re interruptions of certainty. Sketched from life and repeatedly revised, they hover between becoming and undoing.

Color in Lin’s work functions like memory: layered, compressed, occasionally eruptive. Pigments drawn from Dunhuang murals and Miao textiles don’t appear as citation—they pulse through the surface as sedimented time. His practice doesn’t remember in the narrative sense; it compresses, folds, thickens. These are not paintings of culture. They are painted through culture—through exile, exposure, adaptation. The images drift. They don’t claim ground. Instead, they generate it.

What Lin builds, above all, is a space of refusal. The triptych doesn’t unfold in sequence. It disorients. There is no horizon to stabilize the gaze—only interferences. Movement becomes recursive. Time slips. Every panel performs a break, a pause, a vertigo. Diaspora, here, is not background. It’s architecture. The paintings are structured by displacement itself, and thus demand not empathy but instability. The viewer is never safely outside the image. They’re folded into its disturbance.

The mirror, usually a promise of recognition, becomes a betrayal. Instead of likeness, it delivers fracture. Instead of continuity, it multiplies interruption. Lin doesn’t theorize this process—he enacts it. The paintings behave as mirrors misaligned, catching the viewer not in reflection, but in suspense. Every surface delays. Every form reconsiders the terms of visibility. The image doesn’t stabilize—it resists completion.

Homing the Celestial Unseen is not a painting. It’s an event—of seeing, undoing, disorienting. The viewer is not invited to understand, but to endure. Meaning flickers, then disperses. In that dispersion, Cloudslin doesn’t offer revelation. He holds us inside the question.