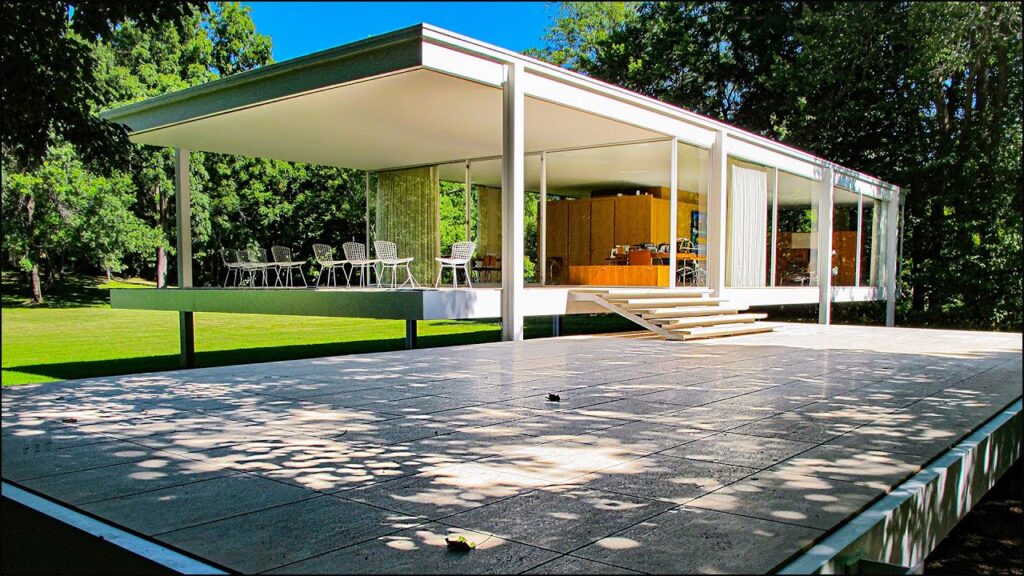

It’s tempting, in telling the story of the Edith Farnsworth House, to break out clichés like “People who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones.” For the residence in question is made predominantly of glass, or rather glass and steel, and its first owner turned out to have more than a few stones for its architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the last director of the Bauhaus, who’d immigrated from Nazi Germany to the United States in the late nineteen-thirties. It was at a dinner party in 1945 that he happened to meet the forward-thinking Chicago doctor Edith Farnsworth, who expressed an interest in building a wholly modern retreat well outside the city. Asked if one of his apprentices could do the job, Mies offered to take it on himself.

The task, as Mies conceived of architecture in his time, was to build for an era in which high and rapidly advancing industrial technology was becoming unavoidable in ordinary lives. Such lives, properly lived, would require new frames, and thoroughly considered ones at that. The shape ultimately taken by the Farnsworth House is one such frame: orderly, and to a degree that could be called extreme, while on another level maximally permissive of human freedom.

That was, in any case, the idea: in physical reality, Farnsworth herself had a long list of practical complaints about what she began to call “my Mies-conception,” not least to do with its attraction of insects and greenhouse-like heat retention (uncompensated for, in true European style, by air conditioning).

Chroniclers of the Farnsworth House saga tend to mention that the central relationship appears to have exceeded that of architect and client, at least for a time. But whatever affection had once existed between them had surely evaporated by the time they were suing each other toward the end of construction, with Mies alleging non-payment and Farnsworth alleging malpractice. In the event, Farnsworth lost in court and used the house as a weekend retreat for a couple of decades before selling it to the British developer and architectural enthusiast Peter Palumbo, who especially enjoyed its ambience during thunderstorms. Today it operates as a museum, as explained by its executive director Scott Mahaffey in the new Open Space video above. Hearing about all the turmoil behind the Farnsworth House’s conception, the attendees of its tours might find themselves thinking that hell hath no fury like a client scorned.

Related content:

A Quick Animated Tour of Iconic Modernist Houses

The Modernist Gas Stations of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe

Why Do People Hate Modern Architecture?: A Video Essay

How This Chicago Skyscraper Barely Touches the Ground

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.