Major music industry companies and organizations are once again throwing their weight behind a proposed law that would prevent rap and other lyrics from being used as evidence in criminal and civil trials.

The Restoring Artistic Protection (RAP) Act was reintroduced in the US House of Representatives on Thursday (July 24) by Georgia Democratic Rep. Hank Johnson and California Democratic Rep. Sydney Kamlager-Dove.

The bill would change the rules of evidence for federal courtrooms, making song lyrics inadmissible unless prosecutors can meet strict criteria, such as showing that the lyrics were meant to be taken literally.

It has the backing of music industry groups such as the Recording Academy and the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), as well as major music companies including Universal Music Group and Warner Music Group.

The issue of using lyrics, particularly rap lyrics, as evidence in trials has been controversial for years, with many lawyers, lawmakers and activists arguing the practice has targeted Black people because of the common practice of describing violent acts in rap lyrics, which are often purely fictional.

“Freddy Mercury did not confess to having ‘just killed a man’ by putting ‘a gun against his head’ and ‘’pulling the trigger’,” Rep. Johnson said in a statement.

“Bob Marley did not confess to having shot a sheriff. And Johnny Cash did not confess to shooting ‘a man in Reno, just to watch him die’.”

“Bob Marley did not confess to having shot a sheriff. And Johnny Cash did not confess to shooting ‘a man in Reno, just to watch him die’.”

Rep. Hank Johnson

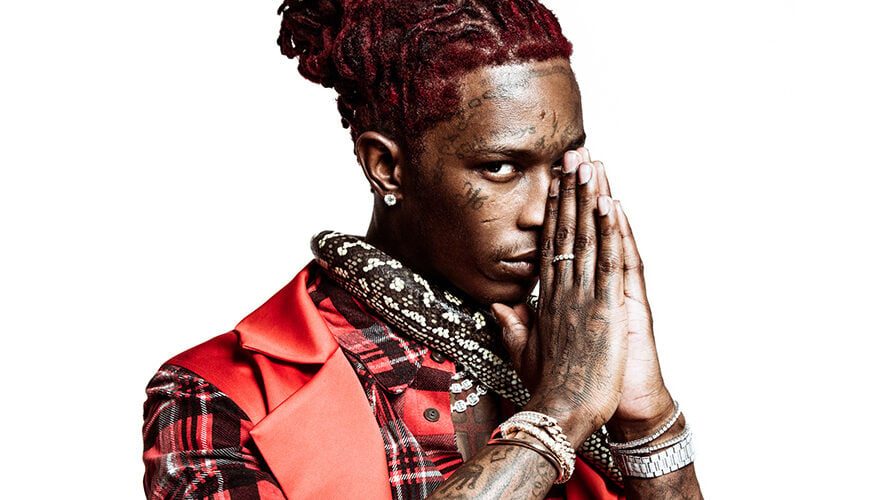

Johnson cited research showing at least 820 instances of creative works being used as evidence in criminal trials. One of the most recent instances involved the criminal trial of Atlanta rapper Jeffery Williams, aka Young Thug, who was charged with running a criminal organization under RICO laws.

Prosecutors alleged that Williams headed up a criminal gang called YSL, or Young Slime Life; lawyers for the rapper argued that YSL was actually Young Stoner Life, a successful record label that is now an imprint of Warner Music.

A judge in the case ruled that prosecutors could use at least 17 specific lines of lyrics from Young Thug and other YSL artists as evidence in the case. Williams’ lawyers argued that this was “racist and discrimination because the jury will be so poisoned and prejudiced by these lyrics/poetry/artistry/speech” that it was tantamount to “unlawful character assassination.”

Williams was released last year after reaching a plea deal under which he was sentenced to time served, which amounted to over 900 days behind bars.

The issue of lyrics as evidence has also come up in Drake’s defamation lawsuit against Universal Music Group over the lyrics of Kendrick Lamar’s 2024 hit Not Like Us, which Drake’s lawyers argue defamed the rapper and endangered him and his family.

In an amicus brief filed in federal court last May, a group of academics urged the judge to dismiss the Drake vs. UMG case, arguing that taking rap lyrics as factual threatens freedom of speech and risks a miscarriage of justice.

“Drake’s defamation claim rests on the assumption that every word of Not Like Us should be taken literally, as a factual representation,” the academics wrote.

“This assumption is not just faulty—it is dangerous.”

The RAP Act was first introduced in Congress in 2022 by Rep. Johnson and New York Democratic Rep. Jamaal Bowman, but the bill failed to make it out of subcommittee and was never brought to a vote on the floor of the House.

The bill’s backers are hopeful it will gain more momentum this time around.

“Weaponizing lyrics or other creative works in court is a harmful tactic that stifles artistic expression and undermines the voices of not just musicians, but all who create and shape culture,” said Recording Academy CEO Harvey Mason Jr.

“With the reintroduction of the RAP Act, we continue to build momentum for ending this unjust practice.”

“With the reintroduction of the RAP Act, we continue to build momentum for ending this unjust practice.”

Harvey Mason Jr., Recording Academy

“Musical lyrics of all genres can be alliterative, fantastical, boastful and at times, even hyperbolic. But what they are not intended to be – or marketed as – is ‘truth’,” said Jeffrey Harleston, General Counsel and EVP, Business & Legal Affairs at Universal Music Group.

“Prosecutorial tactics that use lyrics as ‘evidence’ of guilt without regard to due process and the freedom of expression are deeply disturbing and we commend Ranking Member Johnson for introducing the RAP Act, a commonsense protection against this troubling practice.”

RIAA President and COO Michele Ballantyne said the legislation “will allow all creators to follow their artistic vision without barriers of prejudice. All too often Rap and Hip-Hop artists have been punished for the same kind of hyperbole and imagery other genres routinely use without consequence. Courts should consider relevance, not assumptions.”Music Business Worldwide