This is the second article in a three-part series. (Read Part I here.)

In the first part of this series, we introduced the idea of exotheology—theological reflection on the possibility of extraterrestrial life. The goal was to establish a framework for thinking about alien life without distorting Scripture or drifting into ungrounded speculation. Now, in this second article, we step outside the theological library and into the broader culture to understand how the idea of alien life took hold in the public imagination.

Why is it that, when people hear the word “alien,” they picture little green men in flying saucers?

Why is it that, when people hear the word “alien,” they picture little green men in flying saucers? How did this imagery come to dominate our collective thinking? To answer these questions, we need to trace the evolution of UFO mythology in modern culture—how sightings, media, and myth converged—and clarify what scientists actually mean today when they talk about the search for extraterrestrial life, which often will focus more on microbial organisms rather than humanoid invaders from the stars.

To understand the birth of the modern UFO phenomenon, we need to go back even further than Roswell. In the early 20th century, a curious writer named Charles Fort began collecting reports from unexplained phenomena, strange aerial sightings, and odd weather events. His books, like The Book of the Damned (1919), are now considered foundational texts for the study of the unexplained. Fort never claimed these phenomena were extraterrestrial, but his approach—treating anomalous data as worthy of attention—laid the groundwork for modern ufology. The British monthly magazine Fortean Times is named after him.

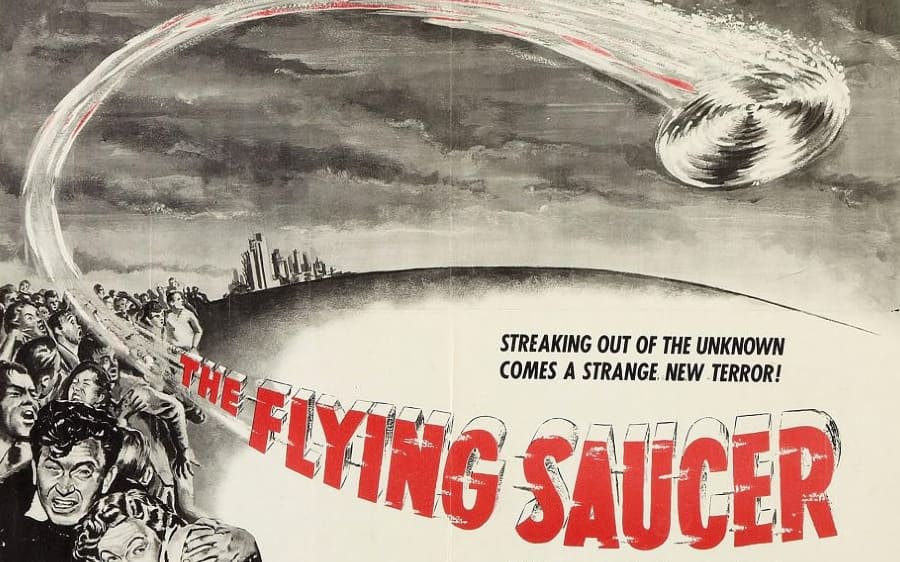

Fast forward to the summer of 1947, when pilot Kenneth Arnold reported seeing nine high-speed crescent-shaped objects flying near Mount Rainier in Washington state. His famous description of the objects led to the press seizing on the word “saucer,” and coining the term “flying saucers” that most people are familiar with today. Just weeks later came the infamous Roswell incident. Something crashed on a ranch in New Mexico. The U.S. Army Air Forces initially reported recovering a “flying disc” but retracted the statement within days, claiming it was a weather balloon. This retraction only deepened public curiosity about these aerial objects, and planted the seeds of government mistrust.

These events occurred in the early Cold War, a time marked by deep technological anxiety. The atomic bomb had dropped only two years earlier. Jet propulsion, rocket engineering, and radar were reshaping the world. It was a cultural moment primed for paranoia and mystery. As reports of unidentified flying objects (UFOs) exploded in the 1950s, the U.S. military scrambled to manage public perception.

The Air Force launched Project Sign in 1948 to investigate UFO sightings. It was followed by Project Grudge in 1949 and then the more well-known Project Blue Book in 1952, which continued until 1969. Thousands of sightings were cataloged and studied. While most were attributed to natural phenomena or misidentifications, a small percentage remained unexplained. The official conclusion was that UFOs posed no national security threat—but by then, the idea that some might be extraterrestrial had taken hold of the public imagination.

This era also saw a rise in colorful personalities who would become cornerstones of American ufology. Gray Barker published works suggesting government cover-ups and introduced the now-infamous “Men in Black” to the popular imagination. John Keel, journalist and author of The Mothman Prophecies (1975), explored the connection between UFOs and paranormal phenomena. His investigations into the Point Pleasant, West Virginia sightings between 1966 and 1967 added a gothic layer to the UFO narrative. Eyewitnesses described a winged humanoid creature—the so-called Mothman—accompanied by strange lights, power outages, and even appearances by enigmatic government agents. While Keel didn’t argue for a straightforward extraterrestrial explanation (he maintained the “ultraterrestrial hypothesis”), his work blurred the lines between UFOs, folklore, and psychological experience, deepening the mystery.

Meanwhile, Stanton Friedman, a nuclear physicist turned ufologist, became one of the most vocal proponents of the extraterrestrial hypothesis. Friedman championed the Roswell case, arguing that it was indeed a crashed alien craft and that the U.S. government had engaged in a systematic cover-up. His lectures and books brought scientific vocabulary to what had often been dismissed as fringe speculation, making him one of the most respected figures in the field.

The damage was done. For many, UFOs and aliens became inseparable.

Throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, UFO sightings were reported across the country with such frequency that the period is often referred to as the “UFO craze.” Sightings weren’t confined to deserts or small towns—they occurred near cities (like Washington, D.C.), airports, and military installations. TV and film responded in kind. From Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956) to Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), UFOs became fixtures of the cinematic imagination. In short, by the late 20th century, UFOs had evolved from ambiguous aerial phenomena to cultural icons synonymous with extraterrestrial contact. The stories, possible sightings, and suspicions of the government became embedded in American consciousness.

It’s important to recognize, though, that the earliest UFO reports, including Arnold’s, did not mention extraterrestrials. The objects were unidentified, but not necessarily otherworldly. So how did the leap from “unknown object” to “alien visitor” happen?

One major factor was Hollywood.

The 1950s saw a boom in science fiction films featuring aliens, often portraying them as invaders or cosmic warnings. The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), War of the Worlds (1953), and countless B-movies about bug-eyed monsters and flying saucers cemented the association in the public mind: strange lights in the sky must be visitors from another world. Books like George Adamski’s Flying Saucers Have Landed (1953) and Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods? (1968) further linked UFOs to extraterrestrial beings, claiming alien encounters and purporting ancient astronaut theories. These works lacked academic rigor but gained enormous popular traction, and those ideas are frequently rehashed on shows like Ancient Aliens today.

By the 1970s and ‘80s, alien abduction narratives had begun to circulate widely. Whitley Strieber’s Communion (1987) and television shows like The X-Files in the 1990s further cemented the cultural narrative: UFOs are spaceships, and aliens are out there watching, probing, and perhaps even manipulating us.

The persistent secrecy surrounding UFO investigations added fuel to the fire. The U.S. government often dismissed reports, redacted documents, and denied access to information. This opacity created a vacuum easily filled by speculation. The culmination of this suspicion may be found in the infamous Area 51 conspiracy theories. The belief that the U.S. government had recovered alien spacecraft (and possibly bodies) and was keeping them hidden in a secret military facility became a fixture of late 20th-century conspiracy culture.

Ironically, the secrecy often had more to do with Cold War espionage and classified aviation technology than with extraterrestrials. Many UFO sightings were later linked to high-altitude spy planes like the U-2 or SR-71. Still, the damage was done. For many, UFOs and aliens became inseparable.

In recent years, the cultural conversation has taken a more serious turn. In April 2020, the Department of Defense officially released videos taken by Navy pilots showing unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP). These videos had previously leaked, but the Pentagon’s confirmation legitimized them in the eyes of the public. This time, the conversation shifted. Instead of discussing alien abductions or crop circles, people began asking legitimate questions: What are these objects? Are they foreign drones? Atmospheric anomalies? Advanced human technology? Or something else entirely?

Government reports, like the 2021 Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) assessment, acknowledged that some UAPs remain unexplained. The language was careful and cautious, but the underlying message was clear: these phenomena are real, and we don’t yet know what they are. Noticeably absent from these reports is direct mention of extraterrestrial life. The conversation, while open to possibilities, has largely returned to data-driven inquiry.

This brings us to a crucial distinction: what scientists mean by “alien life” is often very different from what pop culture imagines. When an astrobiologist, for example, talks about the possibility of life beyond Earth, they aren’t usually imagining intelligent civilizations building cities on Mars. They’re thinking about microbial life—extremophiles that might survive in harsh environments, like beneath the ice of Jupiter’s moon Europa, or in the methane lakes of Saturn’s moon Titan.

We are not responding to Hollywood. We are responding to the cosmos.

Even the discovery of a single-celled organism in the subsurface ocean of Neptune’s moon Triton would be groundbreaking. That would qualify as extraterrestrial life. It wouldn’t have a spaceship or a ray gun, but it would still be life that originated somewhere other than Earth. This is the kind of discovery that scientists at places like NASA, SETI, and the European Space Agency are actively working toward. They’re studying exoplanets in the habitable zone of distant stars, searching for biosignatures—chemical traces that might indicate life on other planets.

Part of the challenge, then, of exotheology, is helping people separate two very different ideas: (1) the cultural mythology of aliens, shaped by decades of film, fiction, and conspiracy, and (2) the scientific plausibility of extraterrestrial life, which is more modest, cautious, and evidence-based. One is driven by storytelling, often sensational or dystopian. The other is driven by empirical inquiry and slow, careful progress. Both can coexist in the imagination, but only one belongs in serious theological or philosophical reflection.

Theological engagement with the possibility of alien life must be rooted in the latter. We aren’t preparing doctrinal statements about alien overlords; we’re asking what it would mean if we found life—even simple life—somewhere else in the universe. That discovery would raise profound questions about creation.

As we transition into the third and final article of this series, we will begin speculating within the framework laid out in Part I, informed by the cultural history surveyed here in Part II. The aim is not to baptize the mythology of aliens, but to ask how Christian theology might responsibly interpret the discovery of non-human life, whatever form it takes. To do that, we need clarity about what the conversation is—and what it isn’t. We are not responding to Hollywood. We are responding to the cosmos. And the universe, as best we can tell, is vast, strange, and still very much under the creative rule of God.

Speculative theology becomes responsible theology when it acknowledges what we do and don’t know. We know the gospel is true. We don’t know if life exists elsewhere. But if it does, we should be ready to respond.