Lego’s The Lord of the Rings: The Shire set contains 2,017 pieces.

On what I can only assume was piece #302, somewhere between placing fireworks in the back of Gandalf’s cart and assembling a tiny hobbit hearth, I burst into tears.

This isn’t an uncommon response for fans of The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, or J.R.R. Tolkien’s works in general: Reddit posts are devoted to tear-inducing moments in the books, and fans congregate online and in person to celebrate the most cathartic, iconic scenes in the films.

Returning to the books and movies and games that marked us in our younger years, we remember that who we are is still, in some way, who we were.

It is less common to weep over a Lego set, but perhaps more telling: a reminder that moving forward sometimes means walking back, that the cultural lampposts God provides in our earliest days can light our way, later, through valleys of considerable darkness.

My mother sparked my early and lifelong Tolkien obsession. She’d never read his works herself. But she knew her daughter had an endless appetite for reading and liked fairytales and myths, and I had recently come home with an excellent report card. To Borders we thusly went, and I emerged with an edition of the trilogy now most well-known for being incredibly ’80s.

I fell in love.

There’s no other way to describe that headlong, enchanted tumble into obsession that we all, at one time or another, experience over a book or a movie or a game. It’s what drives us to memorize the recite the Litany Against Fear or attend sing-alongs, what moves us to get The Princess Bride tattoos or commemorate May 4.

For Christians, such an experience can be doubly meaningful and formative when we discover a cultural artifact that mirrors our faith back to us, or that enlivens—purposefully or not—the values, virtues, and truths we hold dear in new and imaginative ways.

So to say that The Lord of the Rings and Tolkien’s other works formed me spiritually in a way only eclipsed by Scripture itself gives a sense of their significance to my imagination and understanding. I am pleased to have good company in that experience. The text offers exemplars of salvific grace in quiet, seemingly negligible acts of friendship and mercy, the noble goodness of a true king, the triumph of humility against incomprehensible darkness.

The Lord of the Rings film trilogy began the year I started college. My mom and I attended the midnight showing for all three movies. It was her chance to experience the magic she had granted me: in my mind’s eye, still, I can see her beaming from the center of a clutch of cosplaying Ringwraiths and hobbits in our threadbare Cinema 8 lobby.

You might notice I’m writing about her in the past tense.

My mom passed away over two years ago from cancer, after eight months of suffering. It was a hard, horrible time. Perhaps unsurprisingly, God and The Lord of the Rings got me through. I read the trilogy and passages of Scripture on repeat to comfort myself after the doctors said there was nothing more they could do.

Once, on a phone call after she learned that the treatments were not helping, Mom stirred. “Frodo had to go on a long journey,” she told me. “And so do I.”

I stood on the shore, like Sam at the Grey Havens, and I watched her leave.

Faith provides answers and solace for the dark sorrows of bereavement but does not always leaven the sting of loss. To have a mother with Christis to now not have a mother here. We know God will comfort us and be present with us in the valley of the shadow of death, but it is no less a valley for all that. As C. S. Lewis writes in A Grief Observed:

We were promised sufferings. They were part of the program. We were even told, “Blessed are they that mourn,” and I accept it. I’ve got nothing that I hadn’t bargained for. Of course it is different when the thing happens to oneself, not to others, and in reality, not imagination.

Life went on after my mother died, as life is wont to do—which is always the worst and deepest cut of grief. I found solace in my faith. I threw myself into my work. I believed that I was mending, even as I grew unable to watch or read The Lord of the Rings without dissolving into tears. I told myself I was fine.

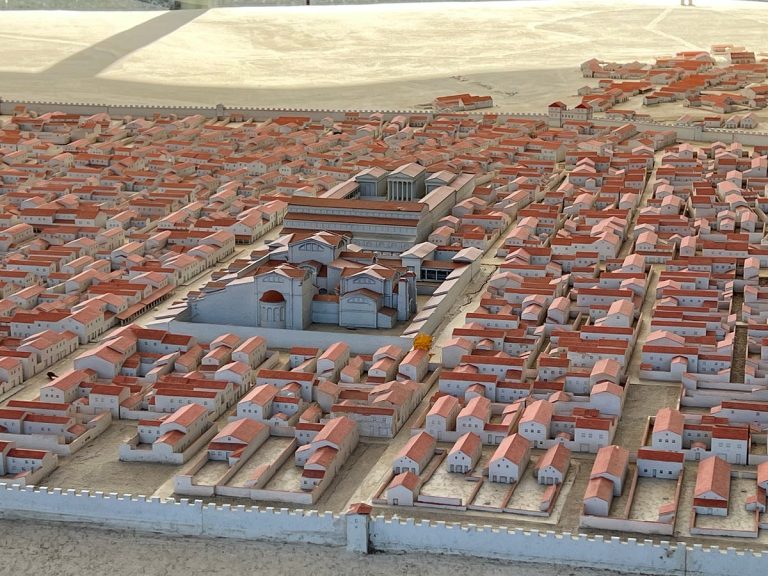

And then, over two years later, Legos: a Shire of 2,017 tiny plastic pieces that I snap together on a tiny folding table in my office. I build Gandalf’s cart of fireworks; I cry. I place tiny sunflowers on Lego grass; I cry. I listen to the Howard Shore movie soundtrack as I rebuild the Shire; I cry. And I heal.

The movies and games and books that move us can be easy to dismiss, particularly in spiritual circles, as ephemera, as the objects of passing and immature affection. Our return to those sites of cultural significance, where we encountered in early years the vivid articulation of something deep inside ourselves, might look on the surface like little more than nostalgia.

And yet what they inspire endures.

What we love—what has become, over time and tide, beloved—can speak our identities back to us in times of profound disintegration and pain, can provide a space for us to participate in the holy transformation that comes in the wake of loss. Returning to the books and movies and games that marked us in our younger years, we remember that who we are is still, in some way, who we were.

Without realizing it, after my mother died, I divided my life into two eras: life with her and life without her. But the small, meditative practice of snapping tiny Lego blocks into place to recreate a world where good exists and hope is fulfilled reminds me in a visceral way that the calculus is not so simple.

Rebuilding the Shire, I am still the child experiencing the magic of the grand new world my mother opened for me. I am still the teenager who was never too cool to tell people I was going to see the midnight showing of The Fellowship of the Ring with my best friend who was also, incidentally, my mom. I am the woman who must keep going without her, and—as I turn my face forward in faith—I am the woman who knows that hurt and loss and sorrow will be redeemed.

“I’m rebuilding the Shire,” I frequently announce to my husband as I slip away to put Legos together. What we both know I mean is that I am myself being rebuilt, renewed, and transformed.

Growing older, we often revisit old favorites in new ways. Our favorite characters change and our sympathies shift. Character arcs we once saw as simplistic hold more nuance. A heroic act to a teenager might read like false virtue to a skeptical adult. Our pop culture loves can become a mirror of sorts through which we see ourselves revealed, a Narnia-like portal where we can visit all of who we’ve been, and are, and are becoming.

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that such a return can be profoundly healing, too.

At the end of The Lord of the Rings, Frodo—bearing the deep spiritual wounds of his journey—recognizes that he must leave the Shire. As part of his preparations to leave, he writes up an account of their journey, leaving an unfinished chapter and several blank pages. “I have quite finished, Sam,” he says to his dearest and best companion. “The last pages are for you.” So, in the same way, are the stories and pop culture gifts of our childhood “for us”: ended, perhaps, by an author or creator, but a perpetual work-in-progress for those who return to see themselves in image, words, or script. In valleys of darkness, these formative works serve as lamplight along the path, artifacts of greater grace—a place of encounter between what is written and what has not yet been told, a site where we might linger and, if we are patient, allow ourselves to be healed.