Alamy

AlamyTragedy Titus Andronicus is the Bard’s goriest work, and a new production is set to be one of the most extreme takes on it yet. It raises the question: why do we watch such brutality?

Good theatre has the power to really move us – a statement that’s usually taken metaphorically, rather than literally. Yet when it comes to Shakespeare’s bloodiest play, Titus Andronicus, its impact can be so visceral it causes audience members to faint. I should know: while reviewing a production at Shakespeare’s Globe in London, back in 2014, its disturbingly violent scenes caused me to start to feel light-headed, even while safely sat down in my seat. Unfortunately, it was a bench with no back: before the end of the first half, I had fainted away completely, falling backwards and waking up in a stranger’s lap.

Warning: this article contains some graphic descriptions of violence

And I was far from the only person to have such a full-bodied response to Lucy Bailey’s production of this gory revenge tragedy: the press went wild for stories of “droppers”, with more than 100 people fainting during the run – testament to the immense power of Shakespeare’s writing, and the skill of performers, as well as to the props department’s handling of litres of fake blood.

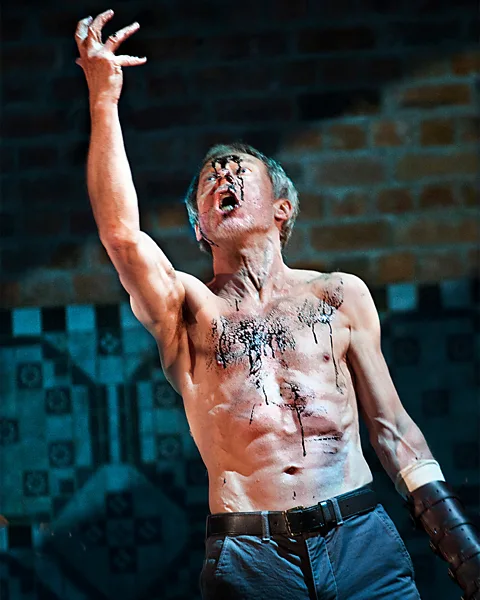

Simon Annand

Simon AnnandOne of the Bard’s earliest plays, written in 1591-2, and almost certainly his first tragedy, Titus Andronicus is a story of violent vengeance: Titus, a general of Rome, returns from wars against the Goths with their queen, Tamora, and her sons held as captives. When her eldest son is sacrificed by Titus, Tamora swears revenge – setting in motion a series of increasingly brutal acts that ends with an infamous scene involving the baking of pies… Boasting 14 deaths, it is the most violent of all Shakespeare’s plays – and now it’s back on stage, with a new production opening at the UK’s Royal Shakespeare Company in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Its fluctuating reputation

The play’s unavoidable ultra-violence has meant that, for much of the performance history of Shakespeare – whose birthday is today – Titus Andronicus was considered a bit of an embarrassment, a bloody stain on his reputation: too gruesome, too over-the-top, to be considered in the same category of greatness as, say, Hamlet or Othello. Then there’s its sometimes queasy tone: the excesses can tip Titus into a gleefully macabre, manic comedy (an aspect also embraced in Bailey’s gore-fest). Let’s just say, the Victorians were not fans.

But the play’s reputation began to revive in the second half of the 20th Century. At the Royal Shakespeare Company alone, there have been several seminal productions in the past 70 years, starring Laurence Olivier (1955), Patrick Stewart (1981), Brian Cox (1987) and David Bradley (2003), while Anthony Hopkins playing Titus on screen in Julie Taymor’s influential, blackly funny film version in 1999 also surely helped boost the play’s standing. Some of these productions leaned heavily on the horror, too: there were fainters and walk-outs in Deborah Warner’s unflinching 1987 production, which Cox once claimed was the most interesting play he’d done and the best stage performance he’d ever given. But he also pointed to the odd humour of the play, calling it “a young man’s play… full of energy, joie de vivre and laughter that often strikes people as ludicrous”.

Titus is not always staged with grisly literalness: in the Olivier-starring production by Peter Brook, the mutilation of Titus’s daughter Lavinia was famously suggested with stylised red streamers – an aestheticised approach also used in the Japanese Ninagawa Company’s production in the 2000s. More recently, Jude Christian’s all-female 2023 production in London’s candle-lit Sam Wanamaker Playhouse enacted the violence on candles themselves, with cast members stabbing, snapping or snuffing them.

In the latest production of Titus Andronicus, however, there will be blood. Buckets of it. “We are doing gallons of blood. We’ve made a sort of wet room [on stage], it’s got a drainage system and an abattoir hook…” says Max Webster, the play’s director, over a video call from Stratford-upon-Avon. He’s had to figure out how to stage no fewer than 27 different acts of onstage violence, from punches through to limbs being lopped off and tongues being cut out. And the only limit on the amount of gore sloshing around is the practical question of how to clean it up between scenes. “It’s an unbelievably boring thing about how many crew members and squeegees it takes,” laughs Webster. “In one sentence, you’re thinking ‘what is the meaning of tragedy in relation to human nature?’ – and then very quickly you get into ‘how many mops can the crew hold?’.”

Marc Brenner

Marc BrennerWebster, whose acclaimed productions include an adaptation of Booker Prize winner Life of Pi and a recent David Tennant-starring Macbeth, wanted to direct Titus Andronicus for one simple reason: Simon Russell Beale, one of Britain’s greatest Shakespearean actors, asked him to. Titus was a part that Russell Beale fancied a crack at, and the RSC was happy to oblige. This version is updated – set in a crisp, besuited modern world riven by conflict, although where exactly is kept deliberately vague.

“It’s trying to be open – we’re not setting it in Kosovo or Gaza or Sudan,” says Webster, adding swiftly “And we’re not going to try to produce the US army onstage or something – it’s trying to make sense of Rome as a ‘superpower of empire’ rather than as ‘the United States of America’.” Still, he sees Titus as freshly, troublingly relevant, in light of shocking events such as the 7 October Hamas attacks, the war in Gaza, and the sudden invasion of Russian troops into Ukraine, the story’s extreme violence doesn’t seem so unimaginable.

In this production, the violence is certainly no laughing matter. In rehearsals, they have been playing it entirely seriously, and eschewing the blackly cartoonish or stylishly Tarantino-esque approach to the violence that some directors explore. This has risks: Webster fully expects that, when the show is in front of an audience, there may be some nervous laughter; it’ll be their job in previews to figure out where these laughs form a necessary “pressure release valve”, and where they’re really just a sign to make the show even more harrowing.

For Webster, it isn’t possible to laugh at the brutality of Titus Andronicus in 2025 – it’s too real. He sees the play as “a howl of pain”; watching it becomes an act of witness, an attempt to face up to atrocities taking place right now – something that he acknowledges could be hard for an audience. “I can walk down the Avon [river], and know my family is safe and it doesn’t feel like the world is burning. But you look at other parts of the world… these horrors, that maybe feel historical to us, are actually happening.”

The psychology behind violent entertainment

But Titus Andronicus isn’t a documentary; it’s an old play, that people choose to stage and choose to pay to go to see. So why, when we could just watch the news, do we opt to watch such harrowing content as art, as entertainment? It’s a question that partly motivated Russell Beale to do Titus, he told The Guardian last week: “I don’t understand the violence. I don’t understand why as an audience we feel excited, stimulated, challenged by it; it’s so relentless.”

Alamy

AlamyIt may have been shunned in later centuries, but Titus Andronicus’s original audiences loved it – and many other forms of graphically horrible entertainment, from bear baiting to public hangings. Titus was a hit in Elizabethan England, and in writing it Shakespeare may, in fact, have been playing to the crowd: it resembles the super-violent revenge tragedies that were popular at the time, rarely-staged works such as Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy and Thomas Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy. Such plays were, themselves, drawing inspiration from the incredibly bloody and outrageous tragedies written by Seneca in the First Century AD – including Thyestes, a source of direct inspiration for Shakespeare, where the title character is fed a pie made of the flesh of his own children. And obviously, Ancient Greek tragedies – even if they keep acts of violence off-stage – are a rich and enduring source of creative murders of family members and cycles of bloody revenge.

Such tragedies, Webster points out, had their origins in ritual performances of sacrifice. “I guess theatre came out of killing goats in Ancient Greece… there’s always been some relationship between theatre and violence and the sacred stuff.”

It does seem that watching the very worst things imaginable unfolding has an irresistible appeal – not only do we still return to Greek or Shakespearean tragedies, but we’ve also turned death and violence into major sources of entertainment, apparently appropriate for daily consumption. Horror films, true crime podcasts, police procedurals, first-person shooter video games… depictions of very, very bad things happening to bodies are pervasive across all art forms, all the time. You might even say we’re addicted to the adrenaline shot we get from such emotionally-wringing, extreme forms of entertainment: research shows that the blood-pumping, heart-racing high we get from fear is close to the pleasurable bodily experience of excitement.

From the high body count of fantasy shows like Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon to the dystopian chills of Squid Game to the seemingly endless appetite for the torture porn movies of the Saw franchise, much of our creative output would make Seneca smack his lips in approval. But beyond the potential physical thrills, why are we so drawn to watching such violent content?

When I ask Webster, he’s as unsure as Russell Beale. “The truth is, I don’t know. But there is a lust to watch violence on-stage – it is a basic human urge.” He wonders if it forms a safe outlet for our innate human darkness. And a common theory as to why we enjoy the terrors of a horror movie or the bleakness of a dystopian novel is just this: that such fictional outings are a secure way for us to rehearse terrible acts – without ever having to experience those in real life. “Maybe it is so we don’t have to do [violence] in our lives?” Webster ponders. “We all have these weird, dark, turbulent fantasies that we don’t talk about because they’re not socially acceptable… so maybe seeing it on-stage is an escape, or a relief?”

Ellie Kurttz/ RSC

Ellie Kurttz/ RSCThe academics Haiyang Yang and Kuangjie Zhang confirm Webster’s theory, sharing research in the Harvard Business Review that found that horror entertainment “may help us (safely) satisfy our curiosity about the dark side of human psyche… As an inherently curious species, many of us are fascinated by what our own kind is capable of. Observing storylines in which actors must confront the worst parts of themselves serves as a pseudo character study of the darkest parts of the human condition.”

If I’m honest, the news that there’s so much blood in Webster’s Titus Andronicus that they need a drain on stage has got me nervous of watching the show, rather than gleefully ready to excise my inner demons. Is he worried that this Titus might be so powerful – so bloody, and so upsetting – that people will faint? He is not. “It’s important you provide a content warning, and then people can make an informed decision about if they want to see it,” says Webster. “If people faint, they faint.”

Titus Andronicus is at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, until 17 June