Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

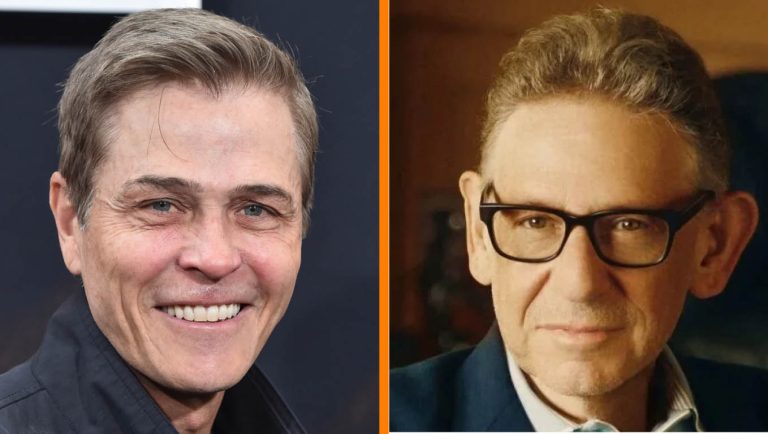

The writer is a biographer of Pope Francis and co-authored ‘Let Us Dream: the Path to a Better Future’ with him

Today, the cardinals mourn and bury Pope Francis. As they do so, they will be casting discreet glances at each other, wondering who will come next.

Nerves will run high in anticipation of electing the 266th successor of St Peter, yet they will not be alone. The cardinals believe their task is to discern God’s choice, and have the Holy Spirit to assist them. For this, they must consider the state of the world and the Church, listen carefully to each other, and keep an open mind and heart. From Monday until they go into conclave in early May, the contours of the next papacy will begin to emerge, in daily discussions in the synod hall, and in informal evening gatherings where they will toss around names. “I’ve heard good things about Cardinal X. What do you know about him?”

As when buying a property, it is one thing to make a list of ideal qualities and another to look at what is actually on the market. No single cardinal can meet every expectation: choices must be made, which in turn reflect priorities. It is here that perspectives vary. But the Conclave cliché of a battle between blocs of “progressives” and blocs of “conservatives” arguing over ethical or doctrinal questions is perhaps the least useful way of framing those disagreements.

It was largely true once, when papal elections were decided by Europeans. But the Catholic Church today is a universal, multi-polar institution made up of many “centres”, a fact that Francis — the first non-European pope in many centuries — sought to reflect in the diversity of his nominations.

Cardinals currently come from 94 different countries. True, Europe remains the heavyweight with 53 electors, yet its congregations are fast shrinking. Most Catholics these days are in the Americas, which have 37 electors. But congregations are growing fastest in Asia and Africa, which have 23 and 18 electors respectively.

While the Church in the west struggles to maintain its heavy legacy of properties, in the southern continents it lacks the resources to build churches and schools fast enough for an expanding flock. Cultural differences now increasingly shape the discussion of ethical questions but these are not so much disagreements over doctrine itself, as to how that doctrine is applied.

It is more useful to frame the differences between the cardinals in terms of how the Church evangelises. How should it bring the Gospel to society, in order to create a home for all that better reflects what Jesus called “God’s Kingdom”? This concerns what one might call the Church’s “style” — its way of being, its culture, its mindset. And here some of the differences between the cardinals run deep, as revealed in their responses to the Francis era.

The late pope’s reforms reflected his profound understanding of what the Church must do in what he called the “change of era” marked by the general expulsion of Christianity from law and culture. Francis deplored the “negative view” of the Church’s diminished social relevance, contrasting it with what he called the “discerning view”. The negative view, born of frustration at the loss of prestige, seeks to recover or shore up what it is attached to. Its criticism of secularisation masks what Francis called a “nostalgia for a sacralised world, a bygone society in which the Church and her ministers had greater power and social relevance”.

The discerning view, in contrast, understands the dramatic shifts of the past few decades as a God-given shock that gives the Church the chance to change both its internal culture and how it relates to the world, in order to better perform what Francis called “God’s style”. Last year, he spoke of the need to embrace a “minority Christianity or, better, a Christianity of witness”. This is a witness of mercy and joy, of humility and service, of simplicity and freedom, of a love that forgives, in which the Church, freed from attachments, can better reflect God’s own way of relating to humanity, and build a more fraternal world.

In the way he exercised the papacy, Francis gave us a masterclass in God’s style. He was a captivating evangeliser, a compelling teacher, engaging and humble, who was attentive to the complexity of people’s lives. Unafraid of diversity, he let all be “seen”, especially those whom society sidelines. The vast numbers in Rome this week are proof of his profound impact.

Yet this style made many leaders in the Church uncomfortable, especially in the US and eastern Europe, where culture-war Catholicism remains strong. Here Francis stands accused of downplaying the demands of doctrine, and of compromising the clarity of Church teaching. Such criticism reveals the idea to which some — not most, but many — cardinals remain attached: of an institution that moralises by teaching, that demands loyalty, confers a cultural identity and seeks alliances of power.

But the world for which that institution was created has moved on. The future of the Church lies now, as in the early centuries, in its witness from below, in its capacity to walk with the seekers and the searchers and the wounded of this world. The struggle of the 2025 conclave will not be over doctrine, but over whether the decline of institutional Christianity is seen as a call to go back and double down, or to wake up to the conversion that Francis so powerfully embodied.