In his lifetime, Jackson Pollock had only one successful art show. It took place at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York in November 1949, and afterward, his fellow abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning declared that “Jackson has finally broken the ice.” Perhaps, according to Louis Menand’s book The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War, he meant that “Pollock was the first American abstractionist to break into the mainstream art world, or he might have meant that Pollock had broken through a stylistic logjam that American painters felt blocked by.” Whatever its intent, de Kooning’s remark annoyed art critic and major Pollock advocate Clement Greenberg, who “thought that it reduced Pollock to a transitional figure.”

It wasn’t necessarily a reduction: as Menand sees it, “all figures are transitional. Not every figure, however, is a hinge, someone who represents a moment when one mode of practice swings over to another.” Pollock was such a hinge, as, in his way, was Greenberg: “After Pollock, people painted differently. After Greenberg, people thought about painting differently.”

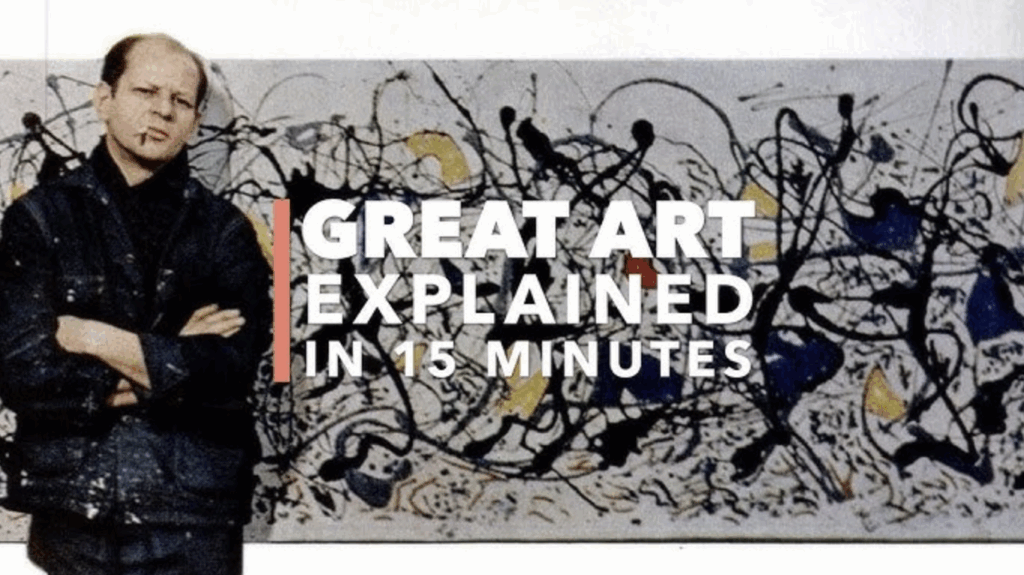

When they made their mark, “there was no going back.” Gallerist-YouTuber James Payne examines the nature of that mark in the new Great Art Explained video above, the first of a multi-part series on Pollock’s art and the figures that made its cultural impact possible. Even more important than Greenberg, in Payne’s telling, is Pollock’s fellow artist — and, in time, wife — Lee Krasner, whose own work he also gives its due.

We also see the paintings of American regionalist Thomas Hart Benton, Pollock’s teacher; Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, in whose workshop Pollock participated; and even Pablo Picasso, who exerted subtle but detectable influences of his own on Pollock’s work. Other, non-artistic sources of inspiration Payne explores include the psychological theory of Carl Gustav Jung, with whose school of therapy Pollock engaged in the late nineteen-thirties and early forties. It was in those sessions that he produced the “psychoanalytic drawings,” one of several categories of Pollock’s work that will surprise those who know him only through his large-canvas, wholly abstract drip paintings. Each represents one stage of a complex evolutionary process: Pollock may have been the ideal artist for the new, post-war American world, but he hardly came fully formed out of Wyoming.

Related content:

Watch Portrait of an Artist: Jackson Pollock, the 1987 Documentary Narrated by Melvyn Bragg

The MoMA Teaches You How to Paint Like Pollock, Rothko, de Kooning & Other Abstract Painters

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.