“Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature.”

-Brian Eno

Eras of art are defined not by their liberties, but by their restrictions. What is dismissed today as ugly or outdated is likely to become tomorrow’s aesthetic ideal, as the acceptance of a neglected or shunned medium is, for the counterculture, a form of rebellion against conformity. Brian Eno’s claim that the physical limitations of recording technologies allow for art styles to stave off ubiquity across generations, is far more relevant today than ever before. Unlike the early 2000s, there are no new garage bands hitting the mainstream with themes of teenage angst and suburban unrest. In those days, the only teenagers who could afford rudimentary recording equipment were the same kids whose parents had spare rooms in the home. Recording music was expensive, gritty, and tied to the resources available to the middle class. Aesthetics were not solely defined by artistic intent, but by economic circumstance. Art today is largely tethered not to what a person possesses, but what they choose to imitate.

Today, recording music has become so accessible that anybody with ample time and an Ableton trial can produce industry-standard works with relative ease. High budget films in twenty years will likely look indistinguishable from the blockbusters of today because CGI has reached photorealism. However, since there is nothing we can’t do, there is nothing we must do. Flip phone cameras looked terrible, so the photos taken on blackberries had to be lo-fi. Photographs taken in Wyoming and Paris in 2003 would be uniquely tied by their medium’s visual qualities, regardless of the intent behind them; images represented a context beyond their subject. In contrast, the iPhone camera is nearly perfect. A photo of a dog no longer represents a time – only a dog. There is nothing a photo must be, so no implicit value tying two images together exists. The idea of accessibility in art to all people may sound like a blessing, but for the modern bohemian, rebellion has manifested in the rejection of these boons. Among Gen Z, rebellion exists not solely against authority, but over-abundance as well. For a generation trapped in a cycle of meaningless consumption, subject to being endlessly force-fed content with little regard for artistic integrity, abundance does not represent blessings. Rather, it represents a bloated, all-consuming vapidness that has infiltrated their artistic inlets. The youth’s cultural diet no longer has room for high art; that space is full. In response, the new bohemian doesn’t want more tools. They want fewer, more meaningful ones.

This pushback against digital perfection has manifested in what might be called the rise of the ‘intentional grain’. From urban centers in Korean islands to the underground arts communities in London, artists have turned to using 1990s camcorders, flip phone cameras and classic radio broadcast microphones to create their works in lieu of the equivalent modern equipment. This progression represents a larger theme in Gen Z’s broader rejection of the modern day’s blindness to their needs and desires. Lo-fi becomes popular when perfect becomes sterile. Cheap is cool when expensive represents inaccessibility. The notion that rebellion lies in friction, in the rejection of abundance, has become the ethos for a generation of artists. Whether rising, mainstream, or underground, creatives across all art forms have begun channeling this sensibility through their own creative contexts. Unified, they represent a culture where authenticity is found not in what’s available, but in what’s left out.

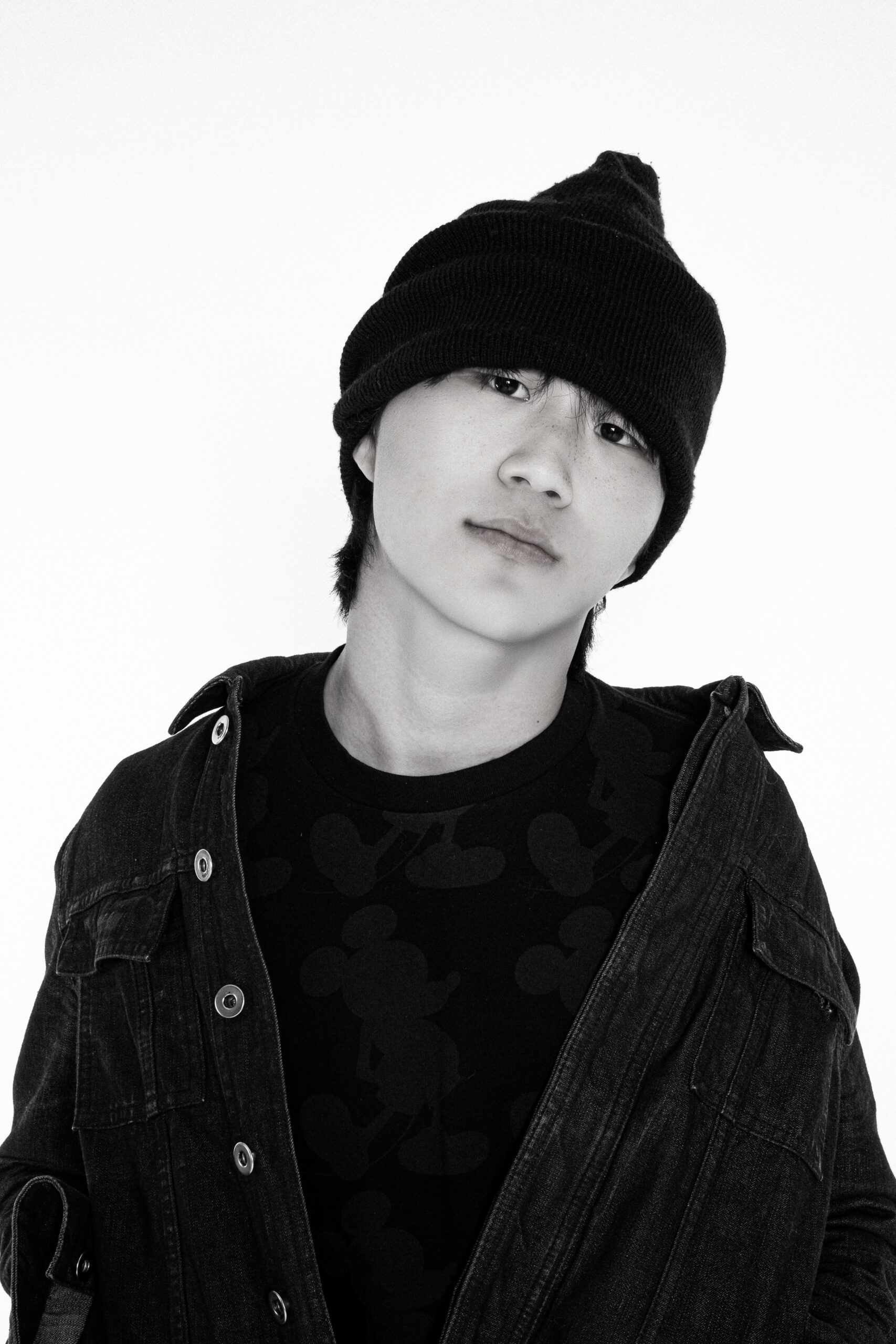

While his schoolmates studied the history of contemporary philosophy, YT studied the recent history of pop culture and its aesthetics. A modern-day English Bruce Wayne, YT began his career stuck between worlds: Oxford student by day, underground rapper by night. Now a college graduate, he continues to entertain a mass audience of consumers and contemporaries alike who have been inspired by his uniquely curated visual and sonic identities. Since the release and subsequent virality of his 2021 track Arc’teryx, YT has gained recognition and acclaim, captivating the masses with his signature brand of jerk-adjacent rap and 2000s-era styled music videos.

The lyrical and musical content of his art holds a certain specificity only truly accessible to those who have lived in similar circumstances as the ones he experienced growing up. Although he presents himself as an embodiment of 2000s party culture in videos such as #Purrr, his songs remain true to his personal identity rather than to a wider culture. Regardless of the lucrative prospect of crossing the pond and gaining recognition in the United States, his art remains inextricably British. YT often makes hyper-specific references to the England he knows, opting to appeal to those who would personally identify with him rather than pandering to the masses by making references to the popular image of Britain or to western urban culture. By choosing to maintain his genuine niche self present in the music and its presentation, YT rejects abundance in favor of sincerity. This quality goes hand-in-hand with his adoption of Y2K aesthetics, a choice he helped popularize in the UK.

YT’s nostalgic imagery prioritizes texture over polish – the inclusion of flip phones and solo cups in his visual artistic output is important not only because of their role in anchoring him to an aesthetic bound to him in particular, but also because they represent an inconvenience. The use of a flip phone in 2025 is an eccentric choice due to the technology being antiquated and the relative inaccessibility we now have to the technology. As it is inconvenient, it is without doubt an intentional decision, and intention is attractive. No one knows where to even buy a flip phone, so seeing a rapper use one in a video simply because they wanted to is endearing.

Although to a lesser extent than YT, Yeat’s acceptance and adoption of Y2K aesthetics as a mainstream US rage rapper speaks to the newfound cultural ubiquity of the style. His Dec. 2024 spread with The Face magazine entitled Welcome to Planet Yeat presents the rapper in a new light, one that embraces the visual motif of the chaotic workplace that was present in 90s and 2000s era cinema. At the time, films such as Joel Schumacher’s Falling Down or David Fincher’s Fight Club used the drab beige wallpaper, gray polyester carpets and tacky cubicle dividers present in office spaces as visual representations of the feelings of insignificance the working class were subject to. Yeat opts to use these liminal spaces as a playground for artistic expression and experimentation, with photographer Moni Haworth capturing photographs of the rapper burning trash, modeling high fashion pieces, lying in a discarded pile of old office chairs and generally expressing comfort within chaos. Yeat’s musical style had always stood at odds with his visual aesthetic, presenting a contrast between his innovative, destructive rage sound and mostly traditional glam rapper persona. His adoption of a visual language defined by distorted and entropic imagery makes sense once one recognizes that the visual distortions present in older imagery mirrors the auditory distortion present in his music today. His sound is uniquely from the 2020s, and yet the visuals of his time fail to match his particular energy. In reality, it likely wasn’t the Y2K era of grainy imagery itself that captivated Yeat. He is simply a better fit in a medium more imperfect than otherwise.

Yeat’s chaotic and heavy electronic style of hip-hop would have been nigh-inconceivable in the nineties. The rapper makes no attempt to hide this, nor has he changed his sound to better fit an older vibe. Maintaining the qualities that bind his music to the 2020s is beyond important to the advancement of hip-hop and popular culture as a whole because the style of rap pioneered by artists such as Yeat or Playboi Carti has been made possible only because of the technical advancements of the decade. Rather than being thoughtful mimicry, the rage sound grew organically within the context of a culture. The few artistic developments that develop over the course of an era are to be cherished because it is these sounds that will become the identifying stamp of the period once future generations begin to consume art from our time. Decades from now, it won’t be the historically safe bets that come to define our era’s mainstream. Rather, it will be the abrasive sounds like Yeat’s that kids will cherish and mimic.

The individuals that spearhead striking visual developments like Yeat’s are often not the faces of the pieces themselves. Often, the public faces of aesthetic projects are subjects in the visions of creative directors and dedicated visual artists whose efforts are dedicated to the contexts surrounding art rather than the consumer art itself. The lack of recognition given to the music video directors, cover art designers and photographers that make rappers’ ability to captivate an audience possible ignores that these visionaries are artists in their own right. It is through these directors that the aesthetic principles entire eras follow are defined. The mainstream follows the underground because the underground has no safety net with which to forgo intention, and is therefore often at the cutting edge. This intention has manifested in the rejection of abundance through the shape of revitalizing the market for the distorted, with photographers and videographers scrambling to get their hands on vintage equipment that represents scarcity and the imperfection that mirrors their imperfect means. In the New York City underground, Kwon Woo Koh has established himself as a key figure in the popular adoption of visual discord. Koh, a Korean national hailing from Jeju Island who went to high school in Lower Manhattan, and who began his career by photographing fashion figures in both Korea and the US, moved towards adopting this vintage aesthetic as he began to work closely with the underground New York rap scene. Koh works as a creative director, designer and photographer that focuses on capturing fashion and the current hip-hop landscape on antique digital formats.

Among his extensive catalog of directorial work in music videos is REM SLEEP, the debut single and video of MILLENIUM that has amassed over 140,000 views on youtube, an impressive point for the debut release of an independent artist. Koh shot and edited the video on an iPhone under the moniker Finale Of 111. His use of the iPhone, perhaps the greatest culprit in reducing the visual identifiability of our current cultural moment, creates a thought-provoking dilemma in the context of the ‘intentional grain’. Although the video was shot on an iPhone, the editing style and graphics make it appear lo-fi. The video is not necessarily tied to today, regardless of the use of current technology. Therefore, was it truly developed in the spirit of embracing the Y2K aesthetic, or simply mimicking it? The reality is, it does not matter. The point of imposing artificial limitations on art is to create defining characteristics through purposeful decisions on the art. In this way, the accessibility of the iPhone and video editing technology makes the creation of art less subject to social and economic barriers, but not necessarily an artistic barrier itself. Koh’s work is exemplary in the context of proving that the endless possibilities provided to artists by modern tools can be a force of artistic liberation rather than creative handcuffs.

Similarly to Yeat, Koh also implements his dilapidated visual style in more mainstream creative pursuits. His photography of a collaboration piece between brands Mowalola and Ksubi maintained his creative vision as a fashion-focused creative director and photographer.

Kwon Woo Koh as an underground visual artist beginning to rise in prominence represents the integral underbelly of popular art and culture as we know it today. Koh shared behind the scenes footage of a video shoot for The Weeknd’s XO brand to his followers on instagram, showcasing his presence in and influence on larger culture as he implemented his own style for the campaign. Seemingly for every music video he shoots for a small artist, he performs another task that acts as an active injection of the underground’s style into the mainstream. It is through these injections of the underground creative spirit that the mainstream can remain alive and thriving, and it is through the support of the mainstream that these artists can find a path in their industry to continue blazing new paths forward.