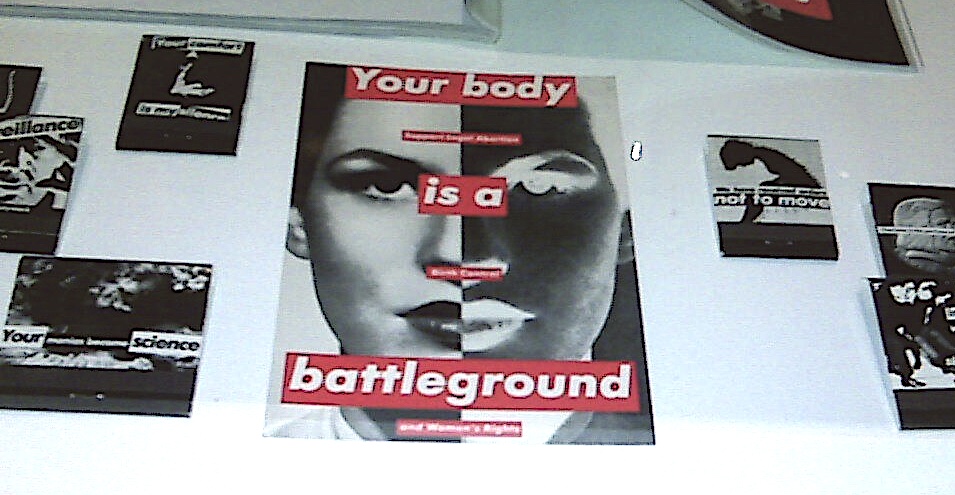

The personal became political during the ‘sex wars’ of the late 1970’s and early 1980’s. With the sexual revolution already underway, Feminism’s second wave brought new issues to the agenda: pornography, consent, sex work and sadomasochism. The AIDS crisis also had its impact – especially given Ronald Reagan’s and Margaret Thatcher’s repressive and regressive policies.

Two distinctive sex wars groups developed in this period: so-called ‘sex-radical feminists’, whose arguments later evolved into what is now known as ‘sex-positive feminism’; and ‘anti-porn feminists’, who were more palatable to conservative factions, and therefore had greater power and presence in the mainstream. Collectively, they strongly condemned male violence, viewed patriarchy as the primary source of women’s oppression and acted against all forms of violence towards women.

Controversial divisions

Opinions diverged on how best to counter the status quo. Debi Sundahl and her partner Nan Kinney, co-founders and publishers of the long-running magazine On Our Backs, for example, once reportedly threw a Molotov cocktail through the window of a pornographic bookstore. Sundahl and Kinney, whose magazine explored bondage-discipline, dominance-submission and sadomasochism (BDSM), lashed out at the porn industry for its exploitation of women. Meanwhile, anti-porn feminists considered that the practice of BDSM reinforced patriarchal patterns and saw pornography as an extension of male violence.

At the heart of the sex wars was a fundamental question about women’s agency. The idea (or ideal) of the woman as a victim, powerless and subjected to violence no longer encompassed women who were part of the liberation movement. Feminists who believed any sexually explicit representation of women was inherently violent expressed their disgust at sexual practices which they labelled as ‘sinful’. In contrast, sex-radical feminists, who believed that informed consent is what distinguishes sex from violence, frequently pointed out the dangers of censorship and the blanket banning of all pornography.

Sex-positive feminists did not fall into the ‘freedom of choice’ trap, as seen in third-wave liberal feminism. As Lisa Duggan, professor and author of many works on the sex wars, explains in one of her essays, sex-radical feminists did not claim that sex workers had ‘free choice’ in their profession. Rather, they emphasized that within the very limited choices available in a sexist, capitalist economy, sex work is not always the worst option. Sex-radical feminists believed that destigmatizing these practices created more opportunities for ethical and fair working conditions than legal restrictions ever could.

In the second wave, ‘political lesbianism’, a branch of lesbian separatism, also emerged. ‘Feminism is the theory, lesbianism is the practice’ was a slogan used by many who saw lesbianism as the only true way to separate completely from men. For example, in ‘Political Lesbianism: The Case Against Heterosexuality’, an article by the Revolutionary Feminist Group of Leeds published in 1979 in Wires, the British newsletter of the women’s liberation movement, it states: ‘We do think that all feminists can and should be political lesbians. Our definition of a political lesbian is a woman-identified woman who does not fuck men. It does not mean compulsory sexual activity with women.’ The article caused division among feminists, and many wrote to the editors expressing displeasure and offense at its content.

Does feminist pornography exist?

At the height of the sex wars, five lesbian sex magazines were released in the US. Their emergence augmented an existing history of lesbian magazines and publications often – though not exclusively – linked to the feminist movement: Vice Versa magazine began publication in the late 1940s; The Ladder was published from 1956 to 1972; and The Lesbian Tide from the 1970s was the first political lesbian magazine to reach a nationwide US audience. Meanwhile, in the UK, the 1960s saw the publication of Arena Three aimed at an apolitical, middle-class audience, which was issued over several years. Then, in the early 1970s, Sappho, the first openly lesbian and feminist magazine in Britain, appeared. However, none of these magazines focused on sex and, for various reasons, remained very modest in their portrayal of lesbianism.

Motivated by the polarized discourse around the feminist art collective that had organized a panel discussion titled ‘Is There Feminist Pornography?’, lesbian sex magazines collectively responded: ‘Yes, there is!’ Indeed, lesbian sex magazines heavily influenced sex wars discourse. The magazines served as a space for sharing information, building community and creating discourse around lesbian sexuality. Erotic fiction, photographs and letters from readers were not just content they were also tools for (re)imagining sexuality and inventing new forms of existence.

As physical objects, lesbian sex magazines brought key tensions among feminist factions to the surface and became sources of controversy themselves. Decisions about whether a feminist bookstore should carry lesbian sex magazines were highly political. Subscribers included lesbians, bisexual women, nonbinary people who identified or didn’t identify as lesbians, trans men and other interested individuals from across the US. Readership at the time was predominantly white; representations of identities such as studs (Black masculine lesbians) did not appear in these magazines until the 1990s.

Magazines varied from DIY publications that didn’t last long to those that were published for twenty years with large circulations. Cathexis: A Journal for S/M Lesbians, for example, was only published twice between 1983 and 1984. Outrageous Women: A Journal of Woman-to-Woman S/M was published in eleven issues from 1984 to 1988, each issue beginning with an editorial statement about consent as an essential part of the SM scene. It also published erotic stories featuring sex between Black and white women, which was extremely rare for depictions of lesbian sexuality at the time. The magazine aimed at a broad audience, regardless of experience or identity. The introduction to the first issue stated: ‘Outrageous Women seeks to provide a safe and lively space in which to discuss, debate and fantasize. We’re open to any woman who is interested in woman-to-woman SM. Our goal is to be all-inclusive with respect to techniques, interests, experience level, intensity, and sexual identity.’

The Power Exchange: A Newsleather for Women on the Sexual Fringe was released in four seasonal issues also from 1984 to 1988. The editorial team had an open P.O. box number where personal ads and letters were sent for ‘Ms. Behaviour’, an advice column. In the first issue, the editor encouraged readers to ‘build a network, at least one on paper, full of mutual support and erotic curiosity.’ These personal ads, mostly from women looking for SM partners, bear witness to the magazine’s widespread readership and broad geographic reach, despite its short lifespan.

All three of these magazines, aimed at lesbians exploring sadomasochistic practices, were printed in black and white with very few images due to their low budgets. One contributor to Cathexis, for example, reportedly snuck into her workplace at night to make bootleg copies of the magazine.

Bad Attitude: A Lesbian Sex Magazine and On Our Backs: Entertainment for the Adventurous Lesbian, both launched in 1984, established themselves as long-running magazines exploring modern lesbian pornography. Respectively available until 2003 and 2006, both covered a wide range of lesbian identity topics. Each issue featured many photographs and illustrations (in full colour from the 1990s), poetry and prose, articles, essays and advice columns. Since they didn’t focus solely on BDSM, their audiences were broader. Reader reactions to depictions of BDSM and interracial scenes, whether critical or supportive, were published in their ‘letters-to-the-editor’ sections. These magazines thus became sites of friction and micro-theory for feminists from either side of the sex wars.

Although the first issue of Bad Attitude, which included ads for Outrageous Women and The Power Exchange, was printed in reverse due to a printing error, the magazine became a reliable, long-term publication under multiple editors. Its influence extended to the representation of racialized women when in 1989, under the leadership of activist Jasmine Sterling, the magazine featured its first Black woman on the cover.

When Canada strengthened its Obscenity Law in 1992, the sale of Bad Attitude formed the basis of a trial against a pornography bookstore owner and employee. While anti-pornography feminists saw the new legislation as a major victory, sex-radical feminists warned of the potential erasure and censorship of queer sexuality and explicit works involving lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender identities. Even after Toronto police seized her magazine, Sterling herself supported the law, acknowledging that it did offer some protection for women and children against violence. However, she warned that ‘the law was written without an understanding of SM or lesbian sexuality…and for this it should be protested.’ After surviving this legal challenge, Bad Attitude continued to be published for another 11 years and today remains one of the most influential lesbian publications.

On Our Backs, the longest-running lesbian sex magazine from the era, preserves important pieces of feminist micro-theory in its letters to the editors and personal ads. The first issue’s Bulldagger of the Season, featuring Honey Lee Cottrell as a desirable butch-lesbian centrefold, implicitly communicated the magazine’s editorial stance in response to some anti-porn-feminist critiques of butch-femme relationships from the start. The image plays with the tropes of traditional porn magazines, reworking what many feminists considered an oppressive genre into a potential source of power and guilt-free pleasure. The portrait sparked a variety of reactions among readers, all of which the editorial team published in subsequent issues.

One reader, signed simply as K., asked whether the centrefold was meant to be arousing or a satire of porn magazines. The question was relevant, given that lesbian sex magazines were gradually shifting lesbian identity toward sexual excitement and the destigmatization of sexuality, as opposed to previously frigid portrayals of lesbianism. Editor Susie Bright, the partner of the lesbian featured in the centrefold, responded: ‘The Bulldagger of the Season was meant to tickle your funny bone, as well as your clit.’ With this, Bright employed the pedagogy of pleasure as a strategy to relax the audience and give K. permission to feel aroused.

In addition to butch identities – some of whom used female, others male pronouns – On Our Backs eventually began to include erotic stories and photos that represented transgender men and women. The magazine became known for transgender self-representation, and by the 1990s, it was one of the first LGBTQIA+ magazines to adopt the term ‘transgender’ in place of the then-outdated ‘transsexuality’.

Redefining sex

Although lesbian sex magazines from the 1970s and 1980s were crucial for sharing information about the sex wars and the HIV epidemic, they remain largely under-researched, and most have not been digitized. Second wave feminism produced diverse zines, magazines and publications; queer people used print media to communicate, theorize and organize before the Internet. However, lesbian sex magazines, despite their engagement with hitherto underexplored non-male identity and sexuality, are not well-known reference points in queer or feminist history.

The ethics and laws surrounding the digitization of pornographic content complicate the present-day accessibility of these magazines. As originally print editions with small circulations, all models and contributors would have to give permission for their images to be digitized before the magazines could be made publicly available to a much wider audience than in the early 1980s. Obtaining those permissions is not impossible as most contributors are still alive, and some libraries could simply censor the photos of individuals who cannot be located. However, the leap from the margins of US print to publicly accessible PDF formats is significant for many contributors whose careers or family lives could be jeopardized by their association with pornographic content.

What nevertheless remains is the fact that these magazines didn’t just depict sex, they redefined it. Their pages dismantled the idea that female sexuality is passive, that lesbian sex is always gentle and that pleasure belongs only in private. Sex became a tool for collectively imagining new worlds and politics. These magazines and their contributors created pornography that continues to push the boundaries of what we consider lesbian and queer sexuality.

This article was first published by Vox Feminae. Its translation from Croatian into English was commissioned as part of Come Together, a project leveraging existing wisdom from community media organization in six different countries to foster innovative approaches.