Photo courtesy of Washington State University.

It’s become fashionable, in recent years, to observe that we live in an increasingly beige-and-gray world from which all color is being drained. Whether or not that’s really the case, all of us still enjoy easy access to a range of colors that nobody in the ancient world could have imagined, and not just through our screens. Look around you, and your eye will soon fall upon some object or another whose hue alone would have looked impossibly exotic in the civilization of, say, ancient Egypt. My coffee cup offers a simple but vivid example, with its blue-green, and maybe yours does too.

“Most ancient pigments were derived from natural resources — ochre, charcoal, or lime, for example,” writes Ben Seal at Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. “In some cases, Egyptians were able to use lapis lazuli, a metamorphic rock that was only found in Afghanistan, to represent the color blue.” But such a “cost-prohibitive and completely impractical” source, as Seal quotes Carnegie Museum of Natural History Egyptologist Lisa Haney describing it, motivated ancient Egyptians to come up with “a process to emulate its intense ultramarine hue. Without a consistent way to represent the beautiful blues of the world around them, they had to get creative.”

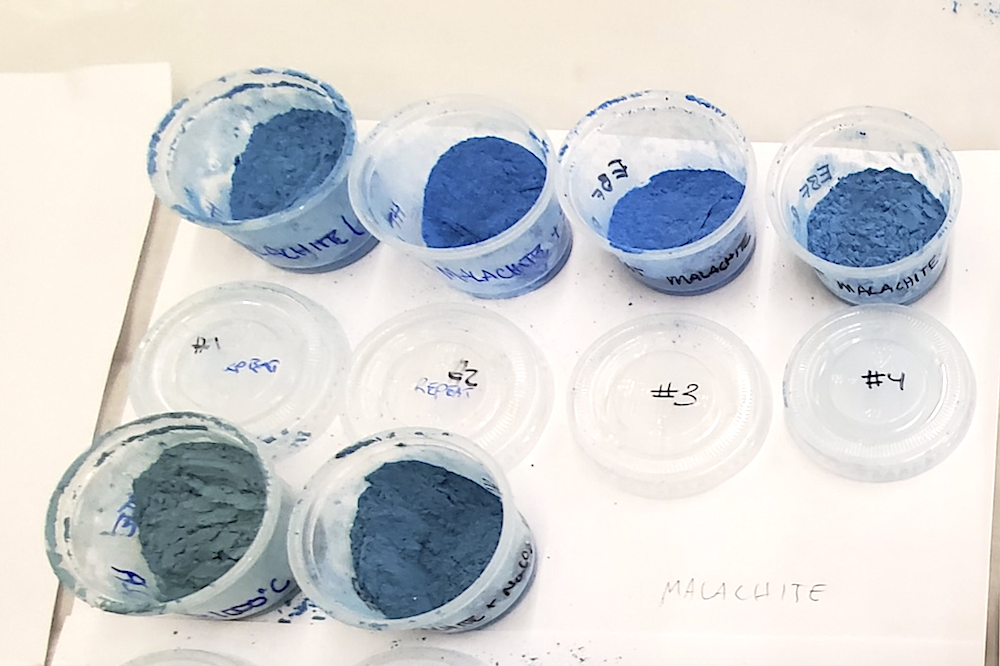

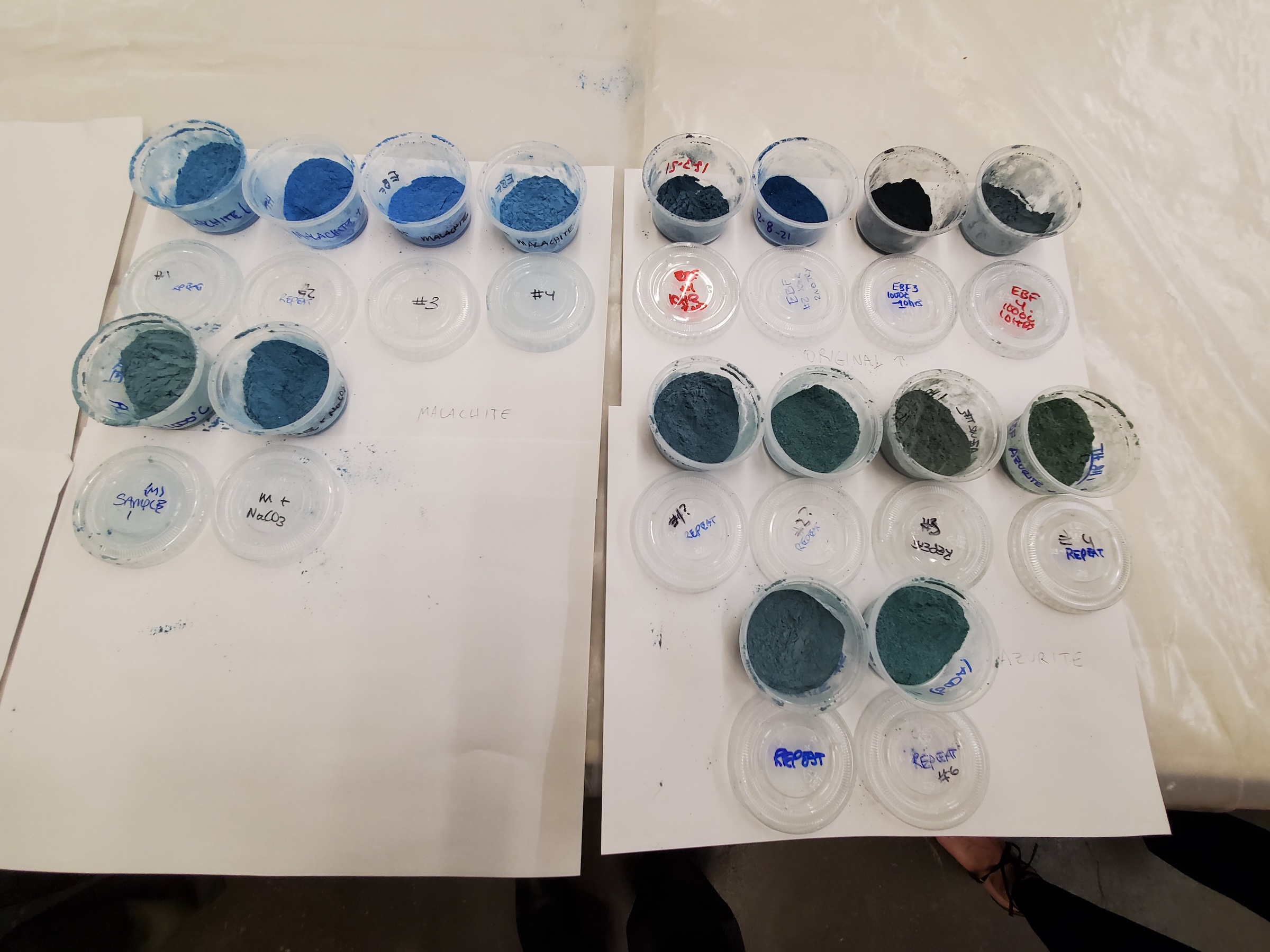

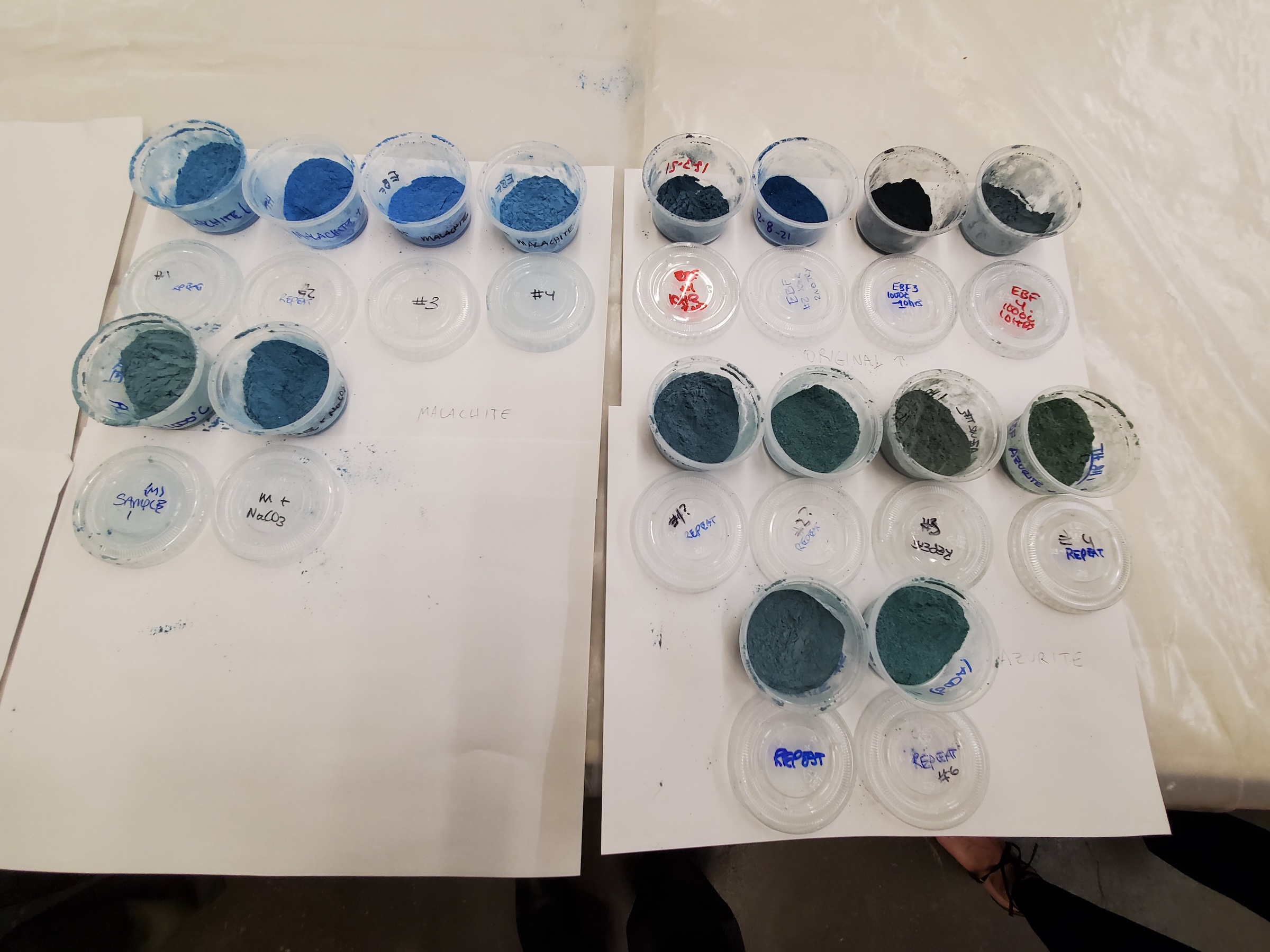

Just this past May, Haney and a team of other researchers from CMNH, Washington State University, and the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum Conservation Institute published a paper on their work of re-creating what’s called “Egyptian blue,” the earliest known synthetic pigment. Extant on artifacts and used also, it seems, in ancient Rome, and at least once in the Renaissance (by no less a Renaissance man than Raphael) its original recipe has since been lost to history. Using period materials like “calcium carbonate that could have been drawn from limestone or seashells; quartz sand; and a copper source” heated to around 1,000 degrees Celsius, Seal writes, “the researchers prepared nearly two dozen powdered pigments in a stunning range of blues.”

Photo courtesy of Washington State University.

The key was to replicate cuprorivaite, “the mineral that gave Egyptian blue such resonance,” and one of those experimental powders turned out to be 50 percent cuprorivaite by volume. The resulting pigment, as Artnet’s Brian Boucher writes, is of more than historical interest, with potential modern uses “due to its optical, magnetic, and biological properties. It emits light in the near-infrared part of the electro-magnetic spectrum, which people can’t see. For that reason, it could be used in applications like dusting for fingerprints and formulating counterfeit-proof inks.” Here in the twenty-first century, we may have all the blues we need, but as in the ancient world, the job of staying one step ahead of counterfeiters is never done.

via Hyperallergic

Related content:

Behold Ancient Egyptian, Greek & Roman Sculptures in Their Original Color

Why Most Ancient Civilizations Had No Word for the Color Blue

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.