Walking around the cobbled streets of Temple, London’s historic legal district and a stone’s throw from the Royal Courts of Justice, is a tourist’s fantasy. With the 12th-century Temple Church at its centre, and gowned barristers flitting between the courts and their chambers, it feels as if you have stepped back in time to a Charles Dickens novel.

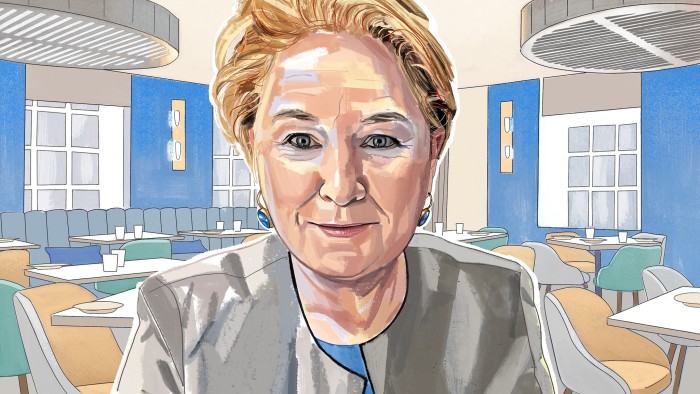

It is therefore fitting that, on an unseasonably hot June day, I’m meeting the area’s main character, the Lady Chief Justice, Sue Carr. Walking around Inner Temple Garden, Carr tells me that — like any top barrister across her brief — she has read both of the Lunch with the FT books “cover to cover” in preparation for our meeting. Still, if she is worried about putting a foot wrong, it doesn’t show.

Given the silence that presides over the English judiciary, where judges are not politically appointed and, for the most part, not allowed to speak publicly, Carr — as head of the judiciary and president of the courts for England and Wales — is one of its few voices, and she rarely gives interviews. A quick tally of the problems she has been confronting gives some clue as to why.

Since 2023, when she became the first woman to hold the position in its nearly 800-year history, Carr has been dealing with record criminal court backlogs, court buildings leaking and crumbling, political over-reach, armchair judges on social media weighing in on cases, and an unprecedented level of threats to judicial safety.

“It feels like every time I see a light at the end of the tunnel, it’s an oncoming train,” she says.

We finish our walk opposite the garden at the Pegasus Bar & Restaurant, a well-known lunch spot for barristers and judges. On a recce to the eatery before our meeting, I’m told by one of the waiters that it’s a great place to eavesdrop on some of the country’s top lawyers as they vent and console each other over their latest judicial dressing-down or failed case.

Our meeting is taking place on a Friday and I inform her that readers often complain about a dry FT Lunch. She gamely agrees to split a bottle of wine and, to my relief, reschedules her next meeting to give us more time to sip our Picpoul. “Here’s to your career,” she says as we clink glasses.

Over olives and bread with a delicious Netherend butter from Gloucestershire, we settle in.

The Temple precinct has been the backdrop to much of Carr’s life. She was a general commercial barrister at nearby chambers, before moving to become a High Court judge across the road, and was married in the church. The garden was quite literally her stage in 1988 when, as a young barrister, she played Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream alongside Lady Simler, one of only two current female Supreme Court judges, as Hermia.

Like Shakespeare’s play, Carr’s job has had a surreal quality at times. Over the past year, she has publicly admonished UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer for overstepping constitutional boundaries and faced criticism of the judiciary for being “woke”.

In February, Tory party leader Kemi Badenoch said to Starmer in parliament that a judge’s decision concerning a family from Gaza, who had been granted the right to live in the UK after they originally applied under a scheme for Ukrainians, was “completely wrong. It cannot be allowed to stand”. Starmer agreed it was “the wrong decision”, though he added the decision had been taken under the previous government’s legal framework.

Following the exchange, Carr said that it was “unacceptable” to make such public remarks, and that it conflicted with the duty of politicians to respect judicial independence.

This led to a deluge of headlines and she had to fend off unwelcome commentary even from within her own ranks. I ask how she felt about former Supreme Court judge Lord Jonathan Sumption telling a radio station that her remarks over the debacle were a “mistake”.

“Nobody actually knows what was going on in those few days except for me,” she says. “I’ve got immigration judges who are terrified, who’ve had to move out of their homes, who aren’t sending their children to school . . . For the judges it was a very important moment for them that somebody spoke out . . . I would do it again in a heartbeat.”

Carr’s German mother is her staunchest defender in such moments. Anyone overheard speaking badly of “Susie” in the supermarket will get an earful from the 86-year-old, she tells me.

Beyond attacks on immigration judges, Carr has also had to grapple with the unprecedented decision by the previous government to use legislation, rather than the courts, to quash the convictions of hundreds of sub-postmasters in the wake of the Post Office scandal, deemed one of the biggest miscarriages of justice in British history.

About 700 sub-postmasters were convicted for alleged offences, including theft and fraud, in cases brought by the Post Office, using data from a faulty IT system.

Carr was vocal about the situation at the time, telling MPs that the court could have handled large numbers of appeals against Post Office convictions, despite the backlogs, and pushing back on the idea that emergency legislation was the only way to deal with it. “The frustration for us was that we could have done the job,” she says.

The Post Office example is just one of a growing tide of cases that has led to social media debate about prosecutions and a lot of “judge bashing”. The conviction of nurse Lucy Letby in 2023 for murdering newborn babies, after which questions have been raised about the evidence presented to the court, is another example of a case that has captured the public imagination.

Carr says that there is no issue with people scrutinising judgments, but such public debate, much of it inevitably uninformed, gives her concern over judicial safety. In a recent survey, nearly 40 per cent of judges in England and Wales said that they felt unsafe in court.

“The point [isn’t] you can’t criticise judgments,” says Carr, adding later that “it was quite telling that in the last UK Judicial Attitudes Survey . . . less than 10 per cent of the judiciary felt valued by government. That makes me sad.”

Is she concerned that this trend for such public discussion about cases, alongside criticisms of “woke judges” from the rightwing media, could lead politicians to interfere more with the judicial process?

“Even if it leads somebody like you to ask the question, there’s the risk,” she says, adding: “If you reflect back 10 or 15 years ago, who would have thought that the judiciary would have been accused of being woke?”

The starters arrive. I have opted for the Greek salad special and Carr has gone for the cured salmon. I realise we have barely made a dent in our bread and olives.

With all of the political mayhem and the challenges facing the courts, why did she want to take up the chief justice job at all?

“I remember being in chambers once when I was still at the Bar, standing next to a photocopier, and a [senior barrister] stood next to me and said, ‘You are going to be the first Lady Chief Justice’ . . . I must have been about 45,” she says. “We just laughed and I said you’re being absolutely ridiculous, and I did think it was ridiculous.”

Writing the application, however, made her realise that she wanted to do it. With her three children grown up, and then in her late fifties, it seemed like there would never be a better moment. She was in fact reportedly on a shortlist of two women in the end.

As the first woman to take up the role she had to make a decision about what to call herself — whether to keep the Lord Chief Justice title or recognise her gender.

“When I thought about it, I asked myself, ‘Why does Lord Chief Justice sound so great?’ Well, actually, for all the wrong reasons, because ‘Lord’ is associated with status and power and command . . . I thought, that’s why I’ve got to take it on, to give ‘Lady’ the same gravitas, the same status, the same power,” she says. “My kids actually wanted me to be ‘Chief [Justice]’ . . . [because it’s] more progressive,” she adds.

I ask if she’s worried about the “glass cliff” theory — where women or ethnic minorities are appointed to positions of power during times of crisis in an organisation and therefore set up to fail.

She says that in fact she was optimistic after Covid-19 about the trajectory ahead of her, and thought “genuinely it was going to be quite calm”. But dealing with the issues around “constitutional boundaries [such as the government’s interference in the Post Office] almost as immediately as I was . . . that was a surprise.”

Menu

Pegasus Bar & Restaurant

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, Crown Office Row, London EC4Y 7HL

Marinated olives £5.50

Bread £6.50

Cured salmon £14.50

Greek salad £9

Prawn skewers £24.50

Roast aubergine £19

Bottle Picpoul de Pinet £39.50

Bottle sparkling water £5.50

Total inc service £140

Carr is determined to use her position to pave the way for others and has made improving diversity at the Bar and in the judiciary — a notoriously pale, stale male environment — one of her key priorities.

She has her work cut out. In the latest round of silk appointments — the elite King’s Counsel kitemark awarded to the country’s top barristers — there were no successful Black applicants. Only five women, including her Shakespeare partner Simler, have ever sat on the UK Supreme Court bench since it was created nearly 16 years ago.

For our main course, I have the roasted harissa aubergine with tabbouleh salad, while Carr opts for the chargrilled chilli prawn skewers, which she declares “delicious”. She tells me that she is not a foodie and is “a really bad cook”, except for HelloFresh meals — dinners that arrive in a box with easy-to-follow recipes — playing into the barrister stereotype that she is good at following instructions.

Carr’s childhood was “happy”, with strong ties to her German grandparents in Bremen. Her father, Richard Carr, is a former director and board member of Arsenal Football Club, and the family, “still a treasured part of the Arsenal community”, go to matches regularly, where she sometimes bumps into Starmer, another Arsenal fan.

Home life in west London is simple. She has “an enormous amount of energy, I don’t need much sleep”, and wakes early so that she can get to her desk around 7am. She has a pad and pen by the bed each night and says that her superpower is an ability to write thoughts coherently in the dark, which used to result in “the killer cross-examination question” when she was a barrister, and now gives her something like “a really good theme for a speech”.

A talented linguist, Carr speaks German and French fluently and, in a sign of her commitment to the brief as head of both the English and Welsh judiciary, she is learning Welsh.

Her linguistic skills have come in handy in her role as an ambassador for the English courts abroad through programmes such as the Standing International Forum of Commercial Courts, which brings together courts from nearly 60 jurisdictions to share practices. She has several chief justice counterparts — in Canada, New Zealand, Northern Ireland — whom she calls on for guidance at times.

It is clear that the English courts cannot continue in their current state. Criminal trials in London are now being scheduled for 2029 because of the backlogs, raising concerns about the fading memories of witnesses. And funding is another challenge; I tell Carr that one high-profile criminal barrister told me recently that they didn’t see how the Criminal Bar would exist in a decade’s time.

Carr counters that it is possible to make a decent living as a criminal barrister “if you work hard”, and that there are lots of initiatives under way to try to better support young people coming into the profession. It is “still one of the greatest jobs in the world”, she says.

As someone who has been a court reporter on and off for the past 15 years, I say I was delighted that Southwark Crown Court, London’s main venue for white-collar crime trials, had recently installed water coolers. However, most of the toilets still don’t flush.

An independent review of the criminal courts is due to be published imminently and is expected to recommend that some jury trials be rolled back so that magistrates alone can deal with certain offences in an effort to speed up cases. Such a recommendation is potentially controversial given the sanctity of jury trials and a person’s right to be tried by their peers.

“The money resourcing situation is pretty challenging and difficult, but I won’t, I just won’t, allow that to jeopardise all the good stuff . . . We’ve got to not talk ourselves into a spiral of collapse,” Carr says.

Despite the fact that legal services is a big revenue generator for the UK (the sector was valued at £44bn in 2022) and the country has a global reputation for its respect for the rule of law, justice is not a vote winner because it is less visible to most of the electorate than areas such as health and education. While Carr has a sympathetic ear in Starmer, a former human rights barrister who, she says, “absolutely gets it” when it comes to the importance of justice, he is of course beholden to political considerations.

Carr’s ideal scenario would be for justice funding to be ringfenced over the next decades to help resolve problems like the backlogs — now at about 77,000 criminal cases — and that the knock-on effects of underfunding are in fact very real for people.

“If families can resolve their divorce and their child arrangements better, their children will be healthier, happier, more likely to get jobs, less likely to commit crimes. They, the parents, will be healthier, happier, more productive at work,” she says.

The problems are not just in Britain. Many countries are dealing with the effects of a deprioritised justice system, while attacks on the rule of law and the US judiciary under President Donald Trump have been felt globally.

Carr says she has little interaction with US judges, although one of her heroes is the late US Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Is she considering some “LCJ” merch like the “Notorious RBG” T-shirts and tote bags that became a cult phenomenon?

“Oh, have you not heard? I want to open a shop in the RCJ . . . I’m going to make some baseball caps,” she says — an idea that she is seriously pursuing — quickly adding that these will not feature images of her.

We are two hours in and Carr does not have time for dessert or coffee. She’s keen to take me to see inside the Inner Temple — one of the four professional associations that barristers in England and Wales belong to — and Temple Church, quickly before she has to leave.

Carr has been sitting for a portrait in recent months and she shows me where it’s going to hang. She’s opted for a “modern working woman” look, she says, because the chief justice robes “were made for men” and don’t fit. Viscount Harcourt, one of a sea of white men on the wall, will be getting the boot to make way for her painting.

There is no fixed tenure on the LCJ job. Carr’s predecessor held the position for six years, one of the longest occupancies in decades. How long does she want to stay in post? “[Until] I do something catastrophically wrong,” she replies. “[Or] stop enjoying it.”

Suzi Ring is the FT’s legal correspondent in London

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram, Bluesky and X, and sign up to receive the FT Weekend newsletter every Saturday morning