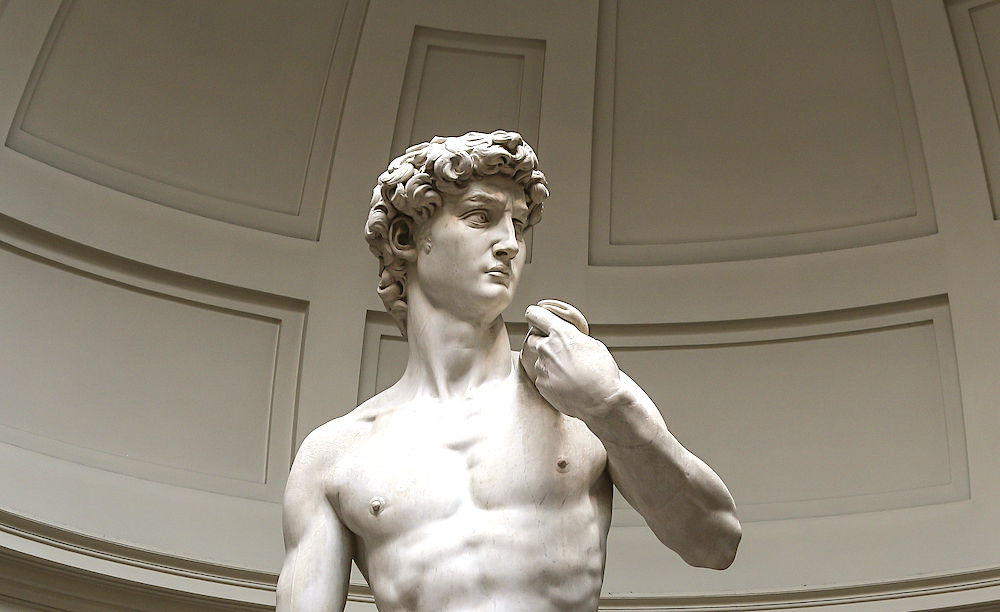

More than a few visitors to Florence make a beeline to the Galleria dell’Accademia, and once inside, to Michelangelo’s David, the most famous sculpture in the world. But how many of them, one wonders, then take the time to view the three other Davids in that city alone? At the Bargello, just ten minutes’ walk away, reside two more sculptures of the young man who would be king of Israel and Judah, both of them by Michelangelo’s fellow Renaissance master Donatello. The less renowned, he made of marble in the late fourteen-hundreds; the more renowned, of bronze in the fourteen-forties, is the subject of the Smarthistory video at the top of the post.

“For a thousand years, the Christian West had looked to the soul as the place to focus. The body was seen as the path to corruption, and so it was not to be celebrated,” says the video’s host Steven Zucker. “What we’re seeing here is a return to ancient Greece and Rome’s love of the body, its respect for the body.”

And to the Florentines of the mid-fifteenth century, as co-host Beth Harris explains, this particular body wasn’t just that of “King David from the Bible,” but that of their own republic as well. Seeing themselves as the David-like underdog victorious over the Goliath that was the Duke of Milan, “they felt blessed and chosen by God” as the “heirs of the ancient Roman Republic.”

Whether or not most everyday citizens of the Florentine Republic felt that way, the banking Medici family, who effectively ran the place for centuries, surely must have. Also at the Bargello is another of the Davids they commissioned, sculpted in bronze by Andrea del Verrocchio in the fourteen-seventies. “Verrocchio gives us a very self-assured young man,” says Harris, with the beauty to be expected of a work of this genre, but also with a certain degree of anti-classicist adolescent awkwardness. In that, the work contrasts with Bernini’s, though both artists created a victorious David, standing over the head of Goliath. Michelangelo, of course, did things quite differently thirty years later, sculpting a David out of marble eternally steeling himself for the battle, at just the moment when his colossal foe comes into view.

Donatello, Verrocchio, and Michelangelo’s Davids all date from the Renaissance. The other unignorable sculpture in this tradition was created much later, in the sixteen-twenties, and also far from Florence. The David by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who would become synonymous with the dramatic extravagance of seventeenth-century Rome, is “like a spring that’s about to unwind,” as Zucker puts it. Unlike when we behold Michelangelo’s contemplative rendition, Harris adds, “here, we’re emotionally, bodily involved,” not just because of the action pose, but also of the physical effort evident in the face. This was the Baroque era, when “the Catholic church is using art as a way to affirm and strengthen the faith of believers.” Ideas about the purpose of art may have changed in the four centuries since, but that hasn’t stopped even the lesser-known Davids from receiving a steady stream of impressed visitors.

Related Content:

Michelangelo’s David: The Fascinating Story Behind the Renaissance Marble Creation

How Michelangelo’s David Still Draws Admiration and Controversy Today

New Video Shows What May Be Michelangelo’s Lost & Now Found Bronze Sculptures

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.