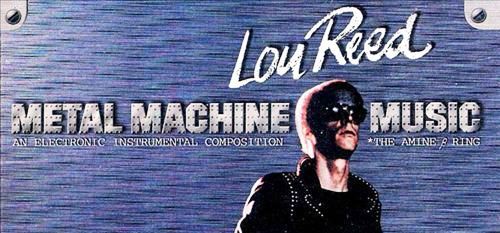

Fifty years ago this month, Lou Reed nearly destroyed his own career with one double album. Metal Machine Music sold 100,000 copies during the three weeks of summer 1975 between its release and its removal from the market. More than a few of the many buyers who promptly returned it would have been expecting something like Sally Can’t Dance, Reed’s solo album from the previous year, whose slickly produced songs went down easier than anything he’d recorded with the Velvet Underground. What they heard when they put the new album on their turntables (or inserted the Quadrophonic 8‑track tape into their decks) was “nothing, absolutely nothing but screaming feedback noise recorded at various frequencies, played back against various other noise layers, split down the middle into two totally separate channels of utterly inhuman shrieks and hisses.”

That description comes from voluble Creem rock critic and avowed enthusiast of decadence Lester Bangs, who also happened to be one of Metal Machine Music’s most fervent defenders. At one point he declared it “the greatest record ever made in the history of the human eardrum.” (“Number Two: Kiss Alive!”)

Much of what we know about the intentions behind this baffling album come from Bangs’ writings, including those that purport to transcribe conversations with Reed himself, who’d been one of the critic’s readiest verbal sparring partners. The inspiration, as Reed explained to Bangs, came from listening to composers Iannis Xenakis and La Monte Young, who dared to go beyond the boundaries of what most listeners would consider music at all. Reed also insisted that he’d deliberately inserted bits and pieces of Mozart, Beethoven, and other classical masters into his sonic maelstrom, though Bangs clearly didn’t buy it.

“Metal Machine Music doesn’t seem so weird now, does it?” asked an interviewer on Night Flight just a decade or so after the album’s release. “No, it doesn’t, does it?” Reed says. “In light of Eno and all this stuff that came out now, it’s not nearly as insane and crazy as they said it was then.” Indeed, it sounds almost of a piece with an influential work of ambient music like Brian Eno’s Music for Airports, though that album was meant to calm its listeners rather than drive them from the room. Over the half-century since its release, Metal Machine Music has accrued enough appreciation to be paid tributes like the live performances by German ensemble Zeitkratzer that have continued long after Reed’s death. The legacy of his “electronic instrumental composition,” as he said after one such concert in 2007, also includes a namesake clause in recording contracts stipulating that “the artist must turn in a record that sound like the artist that the record company signed — not come in with Metal Machine Music.”

Related content:

Teenage Lou Reed Sings Doo-Wop Music (1958–1962)

Hear Ornette Coleman Collaborate with Lou Reed, Which Lou Called “One of My Greatest Moments”

David Bowie and Lou Reed Perform Live Together for the First and Last Time: 1972 and 1997

Lou Reed Creates a List of the 10 Best Records of All Time

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.